THE LORD'S PRAYER: 'OUR FATHER'

Plenarium, Augsburg

Jesus, as one of us, clothed in our flesh and blood, was taught to pray by his mother, Mary. The first prayer a Hebrew mother teaches her son to pray is ' Into thy Hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit' , to be said by the child for the rest of his life before falling asleep, before death. Jesus would have heard her on the Sabbath Eve, at sunset on Friday, blessing the lamps, 'Blessed art thou, O Lord, King of the Universe, who hast given us Thy Commandments and bidst us light these Sabbath lights'. And then, following her, his father Joseph, say 'Blessed art Thou, O Lord, King of the Universe, who hast given us this bread to eat, this wine to drink, fruit of the earth, of the vine, and the work of human hands'.

Mary prayed the Magnificat. Jesus echoed her in the Beatitudes. But then his disciples asked to be taught how to pray, and he gave them a very Jewish prayer. Matthew gives the Prayer in rather crude Greek, behind which one can sense the original Hebrew, Matthew 6.9-15:

In Luke's sophisticated, yet far simpler, Greek version, 11. 2-4, this becomes:

The Lord's Prayer echoes Jewish Prayers to God, hallowing his holy name, speaking of his kingdom, and of the Jubilee's forgiving of all debts, freeing of all slaves, Evelyn Underhill, the Anglican mystic, noting how its seven linked phrases are all in different ways from the Hebrew Scriptures. It combines the texts of Matthew, Mark and Luke.

Strangely some of the best writing on the Lord's Prayer has come from women, from Jews, from outsiders to the Church. For 'Our Father' is the Father not just of sons, but also of daughters, not just of Christ's followers but of all humanity. It is inclusive, not exclusive. In these commentaries to the text the yearning to be free to God will be clear, whose service is perfect freedom. It will sound revolutionary but is not. Revolutions are of Lucifer. The Gospels, of God.

This is the Franciscan tertiary, Angela of Foligno, on Jesus praying, on the Lord's Prayer (Book of Angela Foligno (Instructions), Part II):

Andrea Della Robbia, Jesus in Prayer to the Father, Santa Croce, Sacristy

In a medieval manuscript, contemporary with Julian of Norwich and which may have been written out by her and which is now in Norwich Castle , the original writer of the text, who knew Hebrew, divides the Prayer into seven parts, like the Jewish Candalabra in the Temple, like the seven days of the week, like the seven then-known planets in the heavens. He, or she, writes most movingly of these seven petitions that we make to God in the Prayer Jesus taught us. He and she may be Adam Easton and Julian of Norwich working together in collaboration.

Besides this most beautiful manuscript, with its initial letters in gold upon purple, the colours of wheat and grapes, much like those Boniface sought from English nuns like Lioba centuries earlier, we have also other texts written by women on the Lord's Prayer, Teresa of Avila in the Renaissance, and in our own past century, for instance, Evelyn Underhill's fine book, Abba, also Simone Weil' s superb essay, written when she was teaching it in Greek to her host, Gustave Thibon, and simultaneously reciting it in Greek while harvesting his grapes in southern France.

Norwich Castle Manuscript

Let us go through each of the seven petitions in turn, weaving together aspects from Julian of Norwich, from Teresa of Avila, from Evelyn Underhill, from Simone Weil, being aware that women writing on the 'Our Father ' turn patriarchy into catholicity, undoing all the apartheid of race, religion, class or gender that has crept into the centre of the Church from its edges. Evelyn Underhill even mentionsSt Teresa speaking of an old woman who spent an hour over the first two words, in reverence and in love. Let us, as we say these seven petitions, be like that reverent old woman, and too be like Jewish women lighting and hallowing the Sabbath lights, one for each petition, seven as a whole, healing the children, women and men of this world into God's kingdom of heaven.

I. Our Father, who art in Heaven.

Christ does not have us pray to him, for he calls himself humbly in the Gospels ' the son of man', in Hebrew this being ' Ben-Adam', for ' Adam' in Hebrew means also 'Everyman'. But he requests that we pray with him to 'Our Father ,' whom we share with him, 'Abba ' (Mark 14.36; Romans 8.15; Galatians 4.6), we being his brothers and sisters (Matthew 12.49-50, Mark 3.31-35, Luke 8.19-21). He becomes our brother, emptying himself, even becoming our servant (Philippians 2.5-11); he humbly and lovingly washes our feet, of which we are unworthy (John 13.3-20), and in this he copies Mary Magdalen's loving action and sacrament (Matthew 26.6-13, Mark 14.3-9, Luke 7.37-50, John 12.1-8, though the woman may not be Mary Magdalen). He says, 'Blessed art thou O Lord, King of the Universe who hast given us this wine and bread, fruit of the vine and the earth and the work of human hands' (which is the Jewish Sabbath Prayer said by the father and alluded to in Matthew 26.26-29, Mark 14.22-25, Luke 22.15-20, 1 Corinthians 10.16-22, 11.23-26). He later tragically says, 'Into thy hands, O Lord, I commit my soul' (Psalm 31.5, Luke 23.46). These are Jewish Prayers to God which Jesus prays.

But in Christ's Prayer, we now address God not only as Lord, King of the Universe, as his fearful slaves, but also as 'Abba' (Mark 14.36; Romans 8.15; Galatians 4.6), which is like saying 'Daddy' in English, 'Babbo' in Florentine Italian, as his beloved children, as his sons and daughters. We address someone whom we love and whom we can trust to love us in turn. A father, when his son, his daughter, his co-heirs, ask for bread, neither locks the door nor gives them a stone, nor, when they ask for a fish, does he give them a serpent (Matthew 7.10, Luke 11.11). Julian's Westminster Cathedral/Abbey Manuscript version of the Showings imitates this loving invocation in its opening address to '{ O ur gracious and good Lord . . . . ' We pray, in Christ's words, in Julian's words, for all our 'Evenchristians', as for ourselves; our brothers and sisters, as for ourselves (Matthew 12.46-50; Mark 3.31-35; Luke 8.19-21); in the love of God and of our neighbour (Mark 12.30-31); that we may all be one (John 17). St Cyprian reminds us that this prayer is not for oneself, but for all of us, not 'My Father . . . give me' but 'Our Father . . . give us this day, our daily bread'. And he then speaks of how this Prayer would have been said in that Upper Room of the Pentecost where the Mother of Jesus with other women and the disciples prayed together.

The learned Franco-Jewish philosopher Simone Weil, in her interpretation of the Lord's Prayer, will sometimes cull from the Greek and Platonic traditions, sometimes from the Hebraic. While Spanish Teresa of Avila, whose ancestry was also part Jewish, but who had had no formal education, will ramble in her conversational discourse to her Carmelite Sisters, yet always bring it back to 'His Majesty', King Jesus, a far greater King for her than that of Spain and all the Americas. There was a time when all books were removed from Teresa of Avila and her Sisters. 'Then Christ shall be my book in which I read ', she said, echoing Angela of Foligno. Here she tells her Sisters that it matters not how unruly and chatty one's own mind is in discourse and in prayer, what counts is that the Holy Spirit is present between such a Son and such a Father.

II. Hallowed be thy name.

If and because we hallow him, in the Lord's Prayer's second petition, we then can hallow ourselves, who are his image. But we doom ourselves if we try to hallow ourselves with wealth, power, esteem, riches, might, and love, with the World and the Flesh and the Devil we had promised to renounce at our Baptism. Is our name ' Legion', like the teeming unclean spirits that go into the herd of swine and drown themselves down the abyss (Luke 8.28-31), or is it 'Christian ', who 'one' ourselves with the Son, with the Father, with the Spirit, in Heaven? Dosteivsky in the 'Grand Inquisitor' episode in The Brothers Karamazov, described the need to reject the Devil's temptations, echoing Luke 4.2-8. The Norwich Castle Manuscript sees Pride as that sin which desires to hallow our own names, rather than God's.

'Israel ' in the Jewish 'Prayer of the Good Name ' Jesus prays in Mark 12.29, means 'God will rule', the Shekinah, the Presence of God. Jesus' own name we have failed to hallow, in Hebrew is ' Yeshuah', the ' jah' of 'Hallelujah' 'Alleluia', Joshua, Isaiah, and the ' el' of Israel, Ezekiel, Raphael, Michael, both meaning God. Jesus' name as 'Yeshuah ' means 'God saves'. By hallowing God's name we call down upon ourselves his presence, his Kingdom, in this world, saving us. In this prayer Julian has us ' one' ourselves with and in God. ' Not my name but thine be praised', the Norwich Castle Manuscript states. Yet in blessing and hallowing the Lord Jesus Himself is also paradoxically blessed and hallowed. And so are we all.

Simone Weil, from her Jewish heritage, notes that only God has the power to name himself and that that name is holiness. In hallowing it we free ourselves, she says, from the prison of self. Evelyn Underhill gives us St John of the Cross saying 'The Creation babbles to us, like a child which cannot articulate what it wants to say; for it is struggling to utter the one Word, the Name . . . of God'.

III. Thy kingdom come.

This is interpreted by Julian of Norwich, echoing Angela of Foligno, as meaning ' He is here, Emmanuel, the word made flesh dwelling in us, in the city of our soul, we being his throne.' Origen, On Prayer, XXII.5, p. 148, had said, 'Let our whole life as we pray without ceasing say '' Our Father, which art in heaven'', having its citizenship in no wise upon earth but in every way in the heavens which are God's thrones, inasmuch as the kingdom of God is set up in all those who bear the image of the heavenly and for that reason have become heavenly'.

The Norwich Castle Manuscript gave it as

[The soul of the rightful man or woman is the see and endless dwelling of wisdom that is God's son, sweet Jesus. We do his will and pleasance where we love him with all our might.]

Simone Weil speaks of it as the thirst we have for water, the cry from our whole being.

Outside Settignano, amongst olive groves is a small monastery, that of the Comunità dei figli di Dio, the Community of the Children of God. Its young monks and nuns walk to Mass, like grey sculpted columns. On the chapel's outer wall, so that passers-by may read, are these words:

{ Nessun uomo,

nessuna creatura,

nulla nel cielo e sopra la

terra

ti adora più

nessuno ti conosca o ti

ammiri,

nessuno ti serva, ti ami,

illuminato dallo spirito,

battezato nel fuoco,

chiunque tu sia:

laico, vergine, sacerdote,

tu sei trono di Dio,

sei la dimora, sei lo

strumento,

sei la luce della divinità . .

. .

+++ Dal Cantico di San Sergio di Radonez, Patrono della Russia, 1314-1392.

[All the immensity, the unity which transcends all, is the Holy Spirit. The gift which comes from the abyss and penetrates all and of itself is one and indivisible, fills all things, and transforms all into one light. No one, no creature, nothing of the sky or above the earth could adore you more, no one could know or admire you more, no one could serve you or love you more, illuminated by the Spirit, baptised in flame, whoever you are. Lay person, nun or priest, you are the throne of God, you are his dwelling, you are the instrument, you are the light of God . . . . ]

IV. Thy Will be done on earth as it is in heaven.

These lines of the 'Lord's Prayer' echo those of the Virgin at the Annunciation (Luke 1.38). They echo those of Christ at Gethsemani (Luke 23.42). They echo too those of Jesus said earlier (Matthew 12.46-50, Mark 3.31-35, Luke 8.19-21): 'Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother'. Julian adds, ' This is our Lord's will, that our prayer and our trust be both alike large .' In the Norwich Castle Manuscript this petition is given as the antidote to Envy, that God's will, not mine, be done, in charity, since God is love.

Simone Weil places this desire as that for eternity piercing through that of time. She also analogizes it to one dying of thirst for water, which if it is against God's will, must nevertheless be withheld. Evelyn Underhill gives us Nicholas of Cusa saying, ' I have learned that the place wherein Thou art found unveiled is girt round with the coincidence of contradictions'.

V. Give us this day our daily bread.

Jesus earned his bread as a carpenter, Peter, James and John as fishermen, Paul as a tentmaker. Matthew, when a tax-collector, was guilty of causing the lack of bread to others, but left the money table to follow Christ's simplicity.

Norwich Castle Manuscript says that we can not say 'our bread ' justly if we know of another who lacks it and to whom we do not give it. It adds that we must work for the common profit of our even-Christian, in giving, teaching, helping and comforting. That we are beggars , a phrase echoed in the later Lambeth Manuscript, and day by day beg our bread from God, adding that men who do not work and sweat, make this prayer unworthily. The manuscript adds that there should not be interdicts or excommunication, since no man or woman ought to be parted from Christ's body, Christ having given the sacrament even to Judas. Yet there should be counsel concerning the need to receive the sacrament worthily. The manuscript adds that this petition is the antidote to Sloth. Related to this material is the Latin American Grace: 'We pray that those who lack bread shall have it, and that those who have it, shall hunger and thirst for justice for those who have it not '. Jesus, the Norwich Castle Manuscript notes, said ' My meat is to do my father's will' (John 4.34), linking these two petitions.

Evelyn Underhill quotes a Spanish prayer, 'Thou feedest thy poor ones abundantly with heavenly loaves', and an Irish Gospel ' Give us this day for bread the Word of God from Heaven '. Simone Weil says that Christ is our bread. She adds that, like manna, we cannot store it. The paradox here is that the medieval Norwich Castle Manuscript is more Christian Marxist than is twentieth-century Simone Weil.

Fioretta Mazzei on patience notes that even a piece of bread requires a year of growing and the labour of many hands.

P rova ad avere pazienza: anche per un pezzo di pane

ci vuole un anno di lavoro e molte mani che collaborano.

T ry to be patient: Even for a piece of bread

a year of work and many hands are needed.

VI. Forgive us our sins, our debts, as we forgive those who trespass against us.

In the Hebrew Scriptures at the end of every seven times seven years, in the fiftieth year, the Trumpet shall be blown, the Trump of Doomsday blown, the Bell of Jubilee, the Liberty Bell (for it was the Quakers who had founded Philadelphia fifty years before that bell was cast) rung, all debts be forgiven, all slaves be freed, and the land lie fallow in a great Sabbath of Sabbaths. ' Let Liberty be proclaimed throughout the land ' (Leviticus 25.10).

The Norwich Castle Manuscript, speaking of the Sabbath of Sabbaths, states that those who trespass against us are our Evenchristians. In failing to forgive them, we trespass against God, not doing his will of charity. As David and Augustine said, all of us are debtors to God. Those who forgive are forgiven. The one who is wrathful towards his even-Christian is but 'flesh and worm's meat', and cannot have God's mercy. Augustine says, 'You take heed what man does against you, but not what you do against God, which is worse than what was done to you. For how can he forgive much when you will not forgive even the little debt ' (Matthew 18.21-35). Augustine says God has given it into our power and our will how we shall be judged at Doomsday. This petition is the antidote against the sin of Anger.

Today we learn that those who have been abused are condemned to abuse others in turn - unless they can forgive. Then they are freed from despair and from cruelty. The website Oliveleaf is about such empowering to forgive for freedom. Where we cannot and do not forgive, we are forever in bondage, forever in debt, to those whom we hate. But where we turn hatred into love, we become free. Where we forgive those who hurt us we overcome their evil, we overcome evil itself, and release wellsprings of goodness from our souls into the world, unravelling its harm. Revenge merely copies it, multiplies it, and inevitably damages innocent as well as criminal, storms in tea cups growing into global warfare, the terrible sowing and harvesting of dragons' teeth. The Sandinistas in Nicaragua, whose revolutionary junta included a poet priest, had a peace banner: 'Forgiveness is our revenge', displayed in their centres for re-educating their former Somozista torturers. Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela saw the need in South Africa for Truth and Justice hearings, listening to both sides of the story.

Simone Weil notes that everything we have is a debt. And that we owe also gratitude for any good we may have received as well as reparation for any wrong we think we have suffered. We must renounce the claim of the past on the future. The forgiveness of debts is a spiritual poverty, nakedness, death - turning into life. Evelyn Underhill notes that St Teresa said the saints rejoiced at injuries, because in forgiving them they had something to offer to God. I like my Mother Foundress Agnes Mason's comment, 'Rabbis say that on the Seventh day God could rest, because at last he had made something he could forgive'.

VII. And lead us not into temptation.

The Norwich Castle Manuscript states that 'Blessed is the one who is tried, for he shall win the crown of life', and gives this as the antidote to Gluttony. Lead us not into tempation, for instance the Devil's temptation to Christ that he turn stones into bread.

But deliver us from evil.

In France where this prayer is sung at Mass, it ends with the word 'male', 'evil ', on a high note, turning evil into utter beauty, the people in the congregation having sung the prayer in the Early Christian position of the orans , their hands held up and out into the reciprocating hands of God in blessing/crucifixion. The Norwich Castle Manuscript says of 'Libera nos a malo', at folio 78, that a good man and woman says the Pater Noster and Credo not just for themselves but for all Holy Church. The Manuscript gives this as the antidote to the deadly sin of Lechery, noting that in this request, that God deliver us from evil, we ask freedom for our soul, not thraldom. By hallowing the name of God, through Chastity, the evil of Good Friday becomes the Easter Uprising of the Sunday.

When I talked upon the Lord's Prayer, though I wished to retain most of the translated words, I begged that this line be changed into 'But free us from evil ', into a Julianesque Anglo-Saxon word, rather than a Latinate one. For we keep, in English, the lovely but antique word ' hallowed'. The Lord's Prayer, like the Exodus and its Tau mark, because it and we seek such a hallowing, can free us from sin and death.

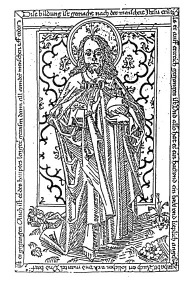

I have been teaching a young gypsy mother from Romania how to read and to write. Her family had been too poor to pay for their daughters' schooling, only that of their sons, so she had never been to school. Remembering the medieval and Renaissance way of teaching children, I had her copy - and she prays from this - the Lord's Prayer in Italian, for we are together in Italy. She is Romanian Orthodox. She sings lullabies to her baby - whom I baptized - of 'Alleluia'. Her people were Christian slaves of Christians in her land for hundreds of years. She has been begging in the streets of Florence to support her family in Romania of seven, and recently was told she could not beg outside the churches. Though single alcoholic men can. This is the first time she copied out the Lord's Prayer, the 'Padre Nostro':

Simone Weil notes that the 'Lord's Prayer' begins with the word 'Father ', and ends with the word 'evil', that it goes from confidence to fear. She also sees how each petition interelates to all the others. She ends by noting:

One imagines her earning her daily bread, picking grapes, in Southern France, and reciting this prayer in the Gospel's Greek, while yearning for her to say it in her own Hebrew. She fled from the Nazis to London and died there of anorexia. Another young Jewish woman philosopher, from Germany rather than France, wrote on Pseudo-Dionysius , became a Carmelite contemplative, like Teresa of Avila , and died in the war in a concentration camp. Her name - Edith Stein . Both were overcome physically by evil; both wrote texts on God, enabling us to overcome evil. These women, his sisters, the first outside the Church, dying unbaptised, the second become a Carmelite nun and today a Christian saint, image Jesus teaching us to pray the Our Father, our Abba.

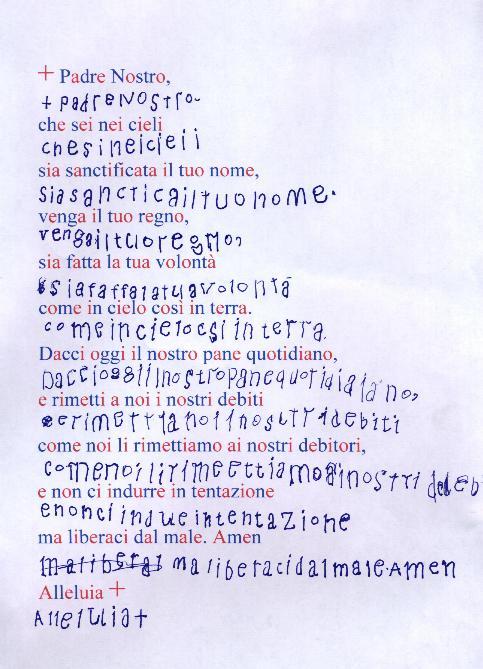

Alan Oldfield, Revelations of Divine Love, 1987.

St Gabriel's Chapel, All Hallows

Convent, Ditchingham

Photograph, Sister Pamela,

C.A.H. Permission, Friends of Julian

Bibliography

The Authorised Daily Prayer Book of the United

Hebrew Congregations of the British Empire. London: Eyre

and Spottiswoode, 5673-1913.

The Greek New Testament.

Ed. Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M.

Metzger, Allen Wikgren. Stuttgart: United Bible Societies,

1983.

The New Oxford Annotated

Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books. Ed.

Bruce M. Metzger, Roland E. Murphy. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1989.

Norwich Castle Museum Manuscript

158.926/4g.5.

Origen. On Prayer. Ed.

Eric Jay. London: S.P.C.K., 1954.

Stein, Edith. 'The Knowledge of

God'. In Writings of Edith Stein. Ed & trans.

Hilda Graef. London: Peter Owen, 1956. Pp. 61-95.

Teresa of Avila. Pater

Noster . Extract from The Way of Perfection.

ICS, 1982.

Underhill, Evelyn. The

Fruits of the Spirit/ Light of Christ: With a Memoir by Lucy

Menzies/ Abba: Meditations Based on the Lord's

Prayer. London: Longman's, 1956.

Weil, Simone. 'Concerning the

Our Father'. The Simone Weil Reader. Ed. George A.

Panichas. New York: David McKay, 1977. Pp. 492-100.

With especial thanks to Kate Lindeman in America who reminds me that St Teresa of Avila had also written on the Lord's Prayer and to Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P., of Kilcullen, Ireland, who gave me a copy of the treatise.

FLORIN WEBSITE © JULIA

BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024: MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO,

DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN:

WHITE SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES TROLLOPE

|| || HIRAM POWERS

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND

BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III, IV, V, VI,

VII

|| MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA

MAZZEI' || EDITRICE AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| FLORIN WEBSITE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA

New:

Dante vivo || White Silence

LIBRARY PAGES: MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || ITS

ONLINE CATALOGUE || HOW

TO RUN A LIBRARY || MANUSCRIPT

FACSIMILES || MANUSCRIPTS

|| MUSEUMS || FLORENTINE LIBRARIES, MUSEUMS

|| HOW TO BUILD CRADLES AND

LIBRARIES || BOTTEGA || PUBLICATIONS || LIMITED EDITIONS || LIBRERIA EDITRICE FIORENTINA ||

SISMEL EDIZIONI DEL GALLUZZO ||

FIERA DEL LIBRO || FLORENTINE BINDING || CALLIGRAPHY WORKSHOPS || BOOKBINDING WORKSHOPS

LIBRARY PAGES: MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || ITS

ONLINE CATALOGUE || HOW

TO RUN A LIBRARY || MANUSCRIPT

FACSIMILES || MANUSCRIPTS

|| MUSEUMS || FLORENTINE LIBRARIES, MUSEUMS

|| HOW TO BUILD CRADLES AND

LIBRARIES || BOTTEGA || PUBLICATIONS || LIMITED EDITIONS || LIBRERIA EDITRICE FIORENTINA ||

SISMEL EDIZIONI DEL GALLUZZO ||

FIERA DEL LIBRO || FLORENTINE BINDING || CALLIGRAPHY WORKSHOPS || BOOKBINDING WORKSHOPS

To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library click on our Aureo Anello Associazione's PayPal button:

THANKYOU!