Incisione, Bruno Vivoli

Repubblica di San Procolo, 2001

FLORIN WEBSITE © JULIA BOLTON

HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO

ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI,

& GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY ||

FLORENCE IN SEPIA ||

CITY

AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS I, II, III,

IV, V, VI,

VII || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA

MAZZEI' || EDITRICE

AUREO

ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA

WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES:

ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

New: Dante vivo || White Silence

LA CITTA E IL LIBRO

II/

THE CITY AND

THE BOOK II

IL

MANOSCRITTO, LA MINIATURA/

THE

MANUSCRIPT, THE ILLUMINATION

ORSANMICHELE,

4-7 SETTEMBRE 2002

V. IL

MANOSCRITTO DAL GOTICO AL RINASCIMENTALE/

THE GOTHIC AND

RENAISSANCE MANUSCRIPT

Incisione, Bruno Vivoli

Repubblica di San Procolo, 2001

THE GOTHIC AND RENAISSANCE MANUSCRIPT

Presiede:

dott.ssa Franca Arduini, Direttrice Biblioteca

Medicea-Laurenziana

La Miniatura fiorentina del Rinascimento,

prof.ssa Mirella Levi D'Ancona, Firenze (italiano,

English)

Tavola Rotonda III: Brunetto Latino, Li

Livres dou Tresor e il Tesoro, Dante, La Commedia

: prof.ssa Alison Stones, University of

Pittsburgh (English); prof.ssa Brigitte

Roux, Université de Genève (French, italiano, English);

prof.ssa Maria Grazia Ciardi Dupré, Università di Firenze

(italiano)

Boccaccio: Le Des

Cas des Noble Hommes et Femmes de Bocace, prof.ssa

Cécile Quentel Touche, Université de Rennes (French,

English)

Appendix:

Female City Builders: Hildegard von

Bingen's Scivias and Christine de Pizan's Livre de

la cité des dames, prof.ssa Christine McWebb, University

of Alberta, Canada (English);

Dante Alighieri e Christine de Pizan,

prof.ssa Ester Zago, University of Colorado, Boulder

(English)

LA MINIATURA FIORENTINA DEL RINASCIMENTO

MIRELLA LEVI D'ANCONA, FIRENZE

* / * =

diapositivi, slides, sinistra/desta, left/right

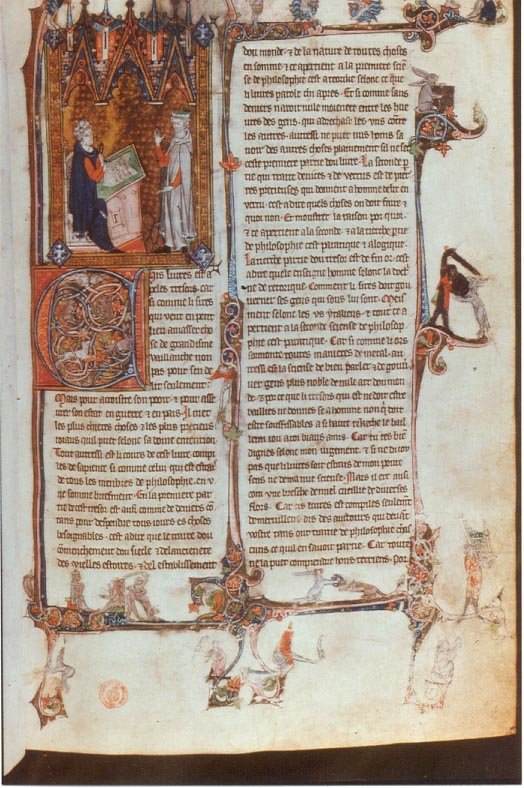

{ Ringrazio il Comitato Scientifico che mi ha invitata e il pubblico che mi é venuto ad ascoltare. Il mio intervento sulla miniatura fiorentina del Rinascimento sarà di necessità superficiale e a grandi linee. Inizierò col tardo Gotico, che é il punto di partenza, per mostrare cosa porti di differenza il Rinascimento. Premetto che le miniature sono molto costose, e che le commissioni agli artisti venivano fatte per esse per lo più dai monasteri e dal Duomo di Firenze. I miniatori nel Trecento erano per lo più dei monaci che operavano nel proprio monastero, mentre nel quattrocento erano quasi esclusivamente dei laici, che operavano nelle botteghe dei cartolai. La maggiore concentrazione delle botteghe era in via dei Cartolai, ora via del Proconsolo. Anche le ricche famiglie fiorentine come i Medici, i Sassetti, gli Ardinghelli, gli Acciaiuoli, ecc., commisero dei libri miniati nel Quattrocento, ma delle loro commissioni purtroppo ora ci restano solo gli stemmi. Mentre che dei monasteri abbiamo una ricca messe di documenti. Tre grandi miniatori emergono nel tardo Trecento: Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci, Don Simone Camaldolese e Don Lorenzo Monaco - tutti tre monaci camaldolesi. E fra i monasteri primeggia Santa Maria degli Angeli nel tardo Trecento e primi del Quattrocento. * 1 / * 2

I thank the Scientific Committee and the Associazione Culturale Biblioteca e Bottega Fioretta Mazzei who have invited me to give this talk and you who have come to hear me. The time given me only allows a brief and superficial survey of this topic. I will start with the Gothic period as the point of departure for what will become Renaissance Florentine book illumination. I need to explain that book illuminating is very costly, and that most of the illuminators were commissioned by the Florentine monasteries and cathedral. In the fourteenth century the illuminators were mostly monks working within their monasteries. Whereas in the fifteenth century, the artists are mostly laymen working in bookshops. These bookshops were mainly concentrated in the Via dei Cartolai, now called the Via del Proconsolo. Eventually, the rich Florentine families, such as the Medici, the Sassetti, the Ardinghelli, the Acciaiuoli, also commissioned illuminated books, but only their coats-of-arms now bear witness to such commissions. At first three great artists come to our attention: don Silvestro dei Gherarducci, Don Simone Camoldolese and Don Lorenzo Monaco, all three Camoldolese monks. Santa Maria degli Angeli is foremost among the monasteries in Florence in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries.

Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci (1339-1399) fu monaco al Monastero di Santa Maria degli Angeli e ne divenne l'abate nel 1398. Nelle sue miniature la figura umana si fonda ed adegua alla decorazine e la luce fa risaltare i colori come gemme. Caratteristico di Firenze é il rosso arancione e vibrante, come si nota in questa Dedicazione della Chiesa a c.1 del Cor.2 della Biblioteca Laurenziana, proveniente dal Monastero di Santa Maria degli Angeli, e datato 1371 nel colophon. Pure nello stesso Corale, alla c. 46 é questa bella S. Agata dove vediamo un'altro colore caratteristico di Firenze: il verde oliva. La figura é soave, ed i fogliami hanno corpo. * 3

A great miniaturist emerges in the late fourteenth century: Don Silvestro dei Gherarducci (1339-1399) who was a monk at the Camoldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence and became an abbot of that monastery. Don Silvestro's illuminations show the human figure as subservient to the decoration of the page and which is fused together with it. Characteristic of Florence in the fourteenth century is the red light which enhances the colors as may be seen in this beautiful Dedication of the Church on folio 1 of Chorale 2 of Santa Maria degli Angeli, now in the Laurentian Library in Florence. It is dated 1371 in the colophon. Also in Chorale 2, at folio 46, is this beautiful St Agatha where we see another dominant colour characteristic of Florence: the olive green in the decoration of the letter. At this period (1371) the decoration is made of bulky leaves; and don Silvestro's figure is sweet, its colours evidenced by light.

Don Simone Camaldolese, che venne da Siena, ma operò a Firenze dal 1375 al 1398 firmò e datò 1381 il Corale 39 della Biblioteca Laurenziana, proveniente dalla Chiesa di S. Pancrazio a Firenze. L'unità della pagina é costituita dalle figure piatte e dalla decorazione marginale a fogliami che fa da cornice al testo.

Another interesting artist is Don Simone Camaldolese, who came from Siena and worked in Florence from 1375 to 1398. He painted Chorale 39, now in the Laurentian Library, in 1381 for the monastery of Saint Pancras and signed its colophon. Here, fol. 1v, the artist keeps the unity of the page by flattening the text as well as the border decoration. The decoration is still with leaves

* 4/ * 5 Il primo passo verso il Rinascimento é fatto da Don Lorenzo Monaco (operoso dal 1390 al 1424), monaco a Santa Maria degli Angeli ma che lasciò il monastero per una bottega propria. Questo stupendo S. Giovanni Evangelista alla c.33 del Corale 1, datato 1396, é modellato dalla luce e si protende nello spazio verso di noi, con il libro in prospettiva e l'aquila che gli fa da leggio. Questa proiezione in avanti nello spazio sarà sviluppata più di due secoli dopo con il Barocco. Caratteristica rinascimentale é l'analisi psicologica nel bel volto del Santo. La luce é solare, altra caratteristica rinascimentale.

Don Lorenzo Monaco (flourished 1390-1424) took the first step towards the Renaissance in this beautiful St John the Evangelist on fol. 33 of Chorale 1 in the Laurentian Library, coming from the monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, where Don Lorenzo was a monk, though he later left the monastery to set up his own bottega. The manuscript is dated 1396, but already the light gives body to the figure which comes forward from the initial letter with the projection of the book drawn in perspective and the jutting forward of the eagle which supports the book. This projection into space is a forerunner of the Baroque period. Already characteristic of the Renaissance is the psychological rendering of the expression in the beautiful face of the saint. The figure is modelled with sunlight, another Renaissance characteristic.

Ma Lorenzo Monaco non si ferma qui, e nel bel Profeta all c. 93 dal Corale 3 nella Biblioteca Laurenziana, proveniente pure da Santa Maria degli Angeli, modella la figura con luce crepuscolare. Questa sperimentazione con luce crepuscolare sarà ripresa solo da un altro grande miniatore fiorentino, Gherardo di Giovanni, alla fine del Quattrocento. In età tarda, Don Lorenzo Monaco sperimenterà pure con effetti di luce notturna, ancora anticipando il Barocco. * 6

But Lorenzo Monaco does not stop at his experience with sunlight, and, in Chorale 3, fol. 33, dated 1409, again from Santa Maria degli Angeli and now in the Laurentian Library, he experimented with light at dusk in modelling this beautiful prophet. This twilight will be taken over at the end of the fifteenth century by another Florentine illuminator, Gherardo diGiovanni. Otherwise all Renaissance books will show sunlight. Later, Don Lorenzo Monaco experiments with night light, already anticipating the Baroque.

Un altro artista minore, seguace di Lorenzo Monaco, é Bartolomeo di Fruosino (1366-1441), che fa sperimenti di spazio limitato, ma empirico e bifocale - cioè da due punti di vista - in questa bella Annunciazione del Cod. F72 del Museo del Bargello c.24v, proveniente dall'Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova. Il Cod. F72 fu rilegato nel 1423, e in quello stesso anno Bartolomeo di Fruosino miniò questa Annunciazione che si ispira ad una Annunciazione tarda di Lorenzo Monaco, a sua volta influenzata dalla Pala Strozzi di Gentile da Fabriano, datata nel marzo del 1423. La scena si svolge davanti ad una camera da letto, con il pavimento visto dall'alto e il soffitto visto dal basso, appunto una prospettiva bifocale. L'Annunciazione di Lorenzo Monaco che la ispirò si trova nella Chiesa di Santa Trinita, ed ha al centro un orto - l'hortus conclusus - con vegetazione rampicante, come fatto da Gentile da Fabriano nella cornice della Pala Strozzi. La prospettiva bifocale in questa Annunciazione di Bartolomeo di Fruosino, come l'andamento sinuoso delle figure é una caratteristica ancora tardo-gotica, ma vi é un primo tentativo di invitare l'occhio nello spazio, caratteristica rinascimentale. * 7/ * 8

A lesser artist was Bartolomeo di Fruosino (1366-1441) who was a follower of Lorenzo Monaco. He illuminated this beautiful Annunciation for the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, now in the Bargello Museum, Cod. F72, fol. 24v. In the illumination Bartolomeo di Fruosino shows a limited space in bifocal perspective - that is, the floor is seen from above, whereas the ceiling is seen from below. The figures float and undulate sinuously, still a late Gothic characteristic. This Annunciation is datable 1423 because the Chorale Cod. F72 was bound in that year and the Annunciation is copied from an Annunciation by Lorenzo Monaco in the church of Santa Trinità in Florence, which in turn was influenced by the Strozzi Altarpiece by Gentile da Fabriano, now in the Uffizi Museum, which is dated March 1423.

La personalità che domina la miniatura fiorentina dagli anni venti del Quattrocento agli anni trenta, e introduce il Rinascimento é Battista di Biagio Sanguigni (1393-1451). Gli attribuisco questo bel Martirio di Santo Stefano nel Graduale D c.51 del Duomo di Prato, proveniente dalla Chiesa di S. Stefano at Prato e datato 1429. Caratteristica del Sanguigni é la divisione in due strati della miniatura, come si vede con un paragone con l'Antifonario documentato nel 1432 che dal Monastero di S. Catherina in San Gaggio é passato alla Biblioteca del Principe Corsini, e ora si trova nel Museo di S. Marco a Firenze. Vedasi nell'Antifonario di S. Gaggio la Decollazione e Sepultura di S. Catherina alla c.32. Entrambe le miniature hanno la divisione in due strati, e la decorazione dell'iniziale a bocce e la divisione di essa a grossi nodi in mezzo. Inoltre nella miniatura di Prato il cielo é blu scuro - un'altra caratteristica del Sanguigni.

Battista di Biagio Sanguigni is the chief illuminator of the late 1420s and the 1430s. I attribute to him this beautiful Martyrdom of St Stephen on fol. 51, of Gradual D from the church of St Stephen in Prato, near Florence, and now in the cathedral of Prato, and which is dated 1429. Characteristics of Sanguigni (1393-1451) are the two-tiered illuminations; the dark blue sky; and the initial letter decorated with balls and tied in the middle by a thick knot. The beautiful St Stephen is still influenced by Lorenzo Monaco in its elongated and sinuous figure, with curving folds in the drapery. I base my attribution of this St Stephen to Sanguigni by comparing it to a documented work by Sanguigni, dated 1432, this Beheading and Burial of St Catherine, fol. 32, which was brought from the convent of San Gaggio, near Florence, to the library of Prince Corsini, and is now in the Museum of San Marco. Laurence Kanter wrongly attributed this documented work to Zanobi Strozzi.

* 9/mantenere8/ Angela Dillon Bussi ha giustamente attribuito al Sanguigni questi magnifici Monaci in Coro alla c.41 del Corale 3 della Biblioteca Laurenziana proveniente dal Monastero di Santa Maria degli Angeli. /1 Abbiamo già visto il Corale 3 a proposito di Lorenzo Monaco che vi ha lavorato a diverse epoche della sua vita. Il Corale 3 é stato scritto nel 1409, ma é stato rilegato nel 1454, e vi hanno collaborato vari artisti. Il Sanguigni vi ha lavorato dopo il 1432, data dell'Antifonario de S. Gaggio, a prima del 1451, anno della sua morte. Aspettiamo la Mostra del Sanguigni e dello Strozzi allestita da Magnolia Scudieri, Direttrice del Museo di S. Marco per maggiori precisazioni sul Sanguigni. I Monaci in Coro sono un capolavoro del Sanguigni per lo spazio in prospettiva che sfonda attraverso una porta, e poi attraverso un'altra; per la magnifica caratterizzazione dei volti dei monaci, e il bianco stupendo delle loro tonache. Il Sanguigni ci porta qui in pieno Rinascimento.

This beautiful illumination of Chanting Monks has been rightfully attributed to Sanguigni by Angela Dillon Bussi. It is Chorale 3, fol. 45, from Santa Maria degli Angeli and is now in the Laurentian Librar y./1 Chorale 3 is dated 1409 and was first illuminated by Lorenzo Monaco, but Lorenzo himself illuminated it at different stages of his life. It is difficult to date the Chanting Monks by Sanguigni, but they must date after 1432, the date of the documented antiphonary from San Gaggio and before Sanguigni's death in 1451. Magnolia Scudieri, Director of the San Marco Museum in Florence, is organizing an exhibition of Sanguigni's works next year and hopefully will give a better dating of Sanguigni's works. The Chanting Monks is Sanguigni's masterwork. The scene is masterfully created by perspective, and opens up in the back through a door, and then yet through another door. The portraits of the monks are wonderful, and so is the beautiful white of their habits. With this illumination, Sanguigni takes us fully into the Renaissance.

* 10/ * 11/ Negli anni quaranta del Quattrocento data questa bella miniatura del Beato Angelico, al secolo Guido di Pietro, che prese il nome di Fra Giovanni da Fiesole come monaco a San Domenico di Fiesole (1400-1455). Faccio vedere a sinistra la pagina intera, e a destra un particolare. Nella pagina intera questa Annunciazione alle c.33v del Cod. 558 del Museo di S. Marco a Firenze, mostra una novità nella decorazione: i fiori nel bas-de-page, che preludono alla decorazione floreale caratteristica del Rinascimento a Firenze. Il particolare mostra il carattere dolce e soave delle figure, che daranno al monaco il soprannome di Beato Angelico.

This beautiful Annunciation by Fra Angelico - whose secular name was Guido di Pietro and who took the name of Fra Giovanni da Fiesole as a monk (1400.1455) - is on fol. 33v of Chorale Inv. 558 of the San Marco Museum in Florence. I show both the full page for its flower decoration which ushers in the floral border decoration of Florentine manuscripts of the second half of the fifteenth century. I also show a detail because it evidences the ethereal and suave figures that gave the name of 'blessed Angelico' to Fra Giovanni.

* 12/ mantenere 11/ Certo non dell'Angelico é questo stupendo gruppo di due figure alla c.199 del Cor. 43 nella Biblioteca Laurenziana, come ben detto da Angela Dillon Bussi./2 E' un artista che ha un vigore aggresività nel colore che esulano dal mite Beato Angelico.

This magnificent group of two standing figures is certainly not by Angelico, as rightfully claimed by Angela Dillon Bussi./2 It is on fol. 199 of Chorale 43 in the Laurentian Library. The strength of the figures, especially the man seen from the back, wrapped in his bulky mantle, and the aggressive colours are foreign to the sweet figures by Fra Angelico.

* 13/ Seguace dell'Angelico é Zanobi Strozzi (1412-1468) che domina la miniatura fiorentina dei tardi anni quaranta e negli anni cinquanta del Quattrocento. Mostro qui una miniatura con la Conversione di S. Paolo alla c.6 del Ms.Inv.515 del Museo di San Marco, datata da documenti nel 1448. Qui le figure sono pienamente rinascimentali, e lo spazio invita l'occhio in profondità fino a molto lontano. E' uno dei capolavori dello Strozzi.

Zanobi Strozzi (1412-1468) is a follower of Fra Angelico. He is the chief Florentine illuminator in the late 1440s and 1450s. I show here his Conversion of St Paul in Chorale Inv. 515, fol. 6, in the San Marco Museum in Florence, dated by documents in 1448. The figures modelled by light are fully Renaissance, and the space leads our eye into the far distance. It is one of Strozzi's masterpieces. Strozzi was Sanguigni's private pupil, but we don't yet have any work which evidences this apprenticeship.

* 14/ * 15/ Dopo la

metà del Quattrocento domina la personalità di Francesco

d'Antonio del Chierico (1433-1484). Mostro qui due miniature

del 1463 che evidenziano la sua bravura sia con figure grandi

nei Corali ne nelle figurine e la decorazione marginale a

fiorami nei manoscritti umanistici di mino formato. La

diapositiva d sinistra mostra la Nascita del Battista

alla c. 48v del Corale Edili 150 della Biblioteca Laurenziana,

Proveniente dall'Opera del Duomo di Firenze, opera documentata

del 1463. Siamo in pieno Rinascimento, e lo spazio é misurato

dalle prospettive con S. Zaccaria e la Vergine Maria con

l'infante

Battista in collo nel proscenio,

poi il letto in prospettiva con la sua bella coperta verde

fiorita, poi ancora le due figure detro al letto - bellissima

é la donna che regge un cesto in testa - ; e finalmente un

paessaggio in lontananza vista da una finestra aperta. Siamo

nel Rinascimento al suo meglio.

Francesco D'Antonio del Chierico (1433-1488) is the chief Florentine illuminator after the middle of the fifteenth century. I show here two of his illuminations which demonstrate his skill in 1463 for his illumination of large figures in choir books as well as the precious flowery decoration of a humanistic book of smaller format. This is the Birth of the Baptist on fol. 48v of Chorale Edili 150 from the Cathedral of Florence and now in the Laurentian Library in Florence, which was commissioned from Francesco D'Antonio del Chierico in 1463. See how the space is measured in perspective with Zachariah and the Virgin Mary holding the infant Baptist in the foreground; the green flowered bedspread in perspective in the middle ground: even the two figures in the background - magnificent the woman holding a basket on her head - and finally a vibrant landscape seen from an open window. This is the Renaissance at its best.

A destra vediamo un altro capolavorio di Francesco d'Antonia: il Plutarco, cod. Plut. 65.26,c.2 con la miniaturina firmata di Teseo e il Minotauro, e una splendida decorazione floreale nei margini. La diapositiva non rende la bellezza dei colori e dell'oro dell'originale. Francesco d'Antonia é inegugliato in questa decorazione. Angela Dillon Russi ha dimostrato con l'aiuto di una lettera datata 1463 che questa miniatura é stata eseguita per il giovane Lorenzo il Magnifico, di cui si vede l'emblema, l'alloro, nel bas-de-page./3

Equally masterful is the precious border flower decoration with golden bars. The gold, the blue and the various colours decorate the borders of the page, glittering like jewes. Angela Dillon Bussi has documented with the help of a letter dated 1463 that the decoration of this fol. 2, in Plut. 65.26, signed F.D.A. , Francesca D'Antonia, was made for the young Lorenzo the Magnificent of which we see the laurel - his emblem. /3

* 16/ Accanto alla decorazione floreale si svolse dal 1432 al 1473 la decorazione a bianchi nastri intrecciatti, detta 'bianchi girari' da Paolo D'Ancona. Mostro a sinistra un frontispizio di Giuseppe Flavio nel Ms. Plut. 66.3.c.1 della Biblioteca Laurenziana, databile negli anni 60 del Quattrocento. Moltissimi artisti si cimentarono in questa tecnica dei bianchi girari.

In the years 1432-1473 there developed side by side with the floral decoration another kind of decoration with white interlaces called 'bianchi girari' Paolo D'Ancona. This white scroll decoration is in a manuscript of Flavius Josephus Ms Plut. 66.3, fol. 1, in the Laurentian Library, datable in the 1480s. Many artists adopted this type of decoration.

Bargello, Cod. A67, fol. 5

* 17/ E ora veniamo al maggior miniatore fiorentino del Rinascimento, Gherardo di Giovanni (1446-1497). Gherardo ha miniato la c.5 con l'Annunciazione nel Messale A 67 del Museo del Bargello, proveniente dall'Ospedale di S. Maria Nuova a Firenze, come si vede dalla gruccia, in alto, emblema dell'Ospedale. Il Cod. A 67 é documentato dal 1474. Le figure sono stupende, bagnata di luce solare, e con la tecnica dello sfumato nei volti. Lo sfumato é la tecnica che passa gradualmente dalle luce in ombra come se fosse fumo. Oltre allo sfumato, nello stupendo paessaggio che sfonda a sinistra, a destra, e poi in lontananza all'infinito, vi é la tecnica della prospettive aerea. La densità dell'aria funge come una nebbia che dissolve nel'azzurrino gli oggetti in lontananza.

Le due techniche dello sfumato e della prospettiva aerea erano appena state inventate da Leonardo da Vinci nell'Angelo e nel paessaggio di sinistra nel Battesimo di Cristo del Verrocchio ora nel Museo degli Uffizi. Ma non basta. La scena di Gherardo é bagnata di luce solare, mentre nei medaglioni nel margine sono scene dell' Inferno di Dante con luce crepuscolare o notturna.

Gherardo di Giovanni (1446-1497) is the greatest Florentine illuminator of the Renaissance. This magnificent Annunciation is on fol. 5 of Ms A 67 in the Bargello Museum, coming from the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, as evidenced by the crutch, its emblem. It is a documented work by Gherardo in 1474. The artist uses two techniques newly invented by Leonardo da Vinci in the angel and landscape of Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ, datable circa 1470, and now in the Uffizi Museum. The 'sfumato' and aerial perspective. The 'sfumato', used in the faces of the angel and the Virgin Mary, is the gradual passage from light to shadow as if it were smoke - 'fumo' in Italian. The aerial perspective, used by Gherardo in the distant landscape, is the technique whereby the mass of the air by its density appears as a bluish veil which dissolves the objects in the far distance. The space in this Annunciation is infinite, continuing at right, at left, and in the distance dissolved in aerial perspective. The scene is bathed in sunlight, and the angel is superb. But this is not all; the medallions in the border with scenes from Dante's Inferno lack sunlight; given at dusk or at night. This experiment with nocturnal light will be taken over only in the Baroque period.

Questa iconografia è interessante perchè mostra che la Vergine Maria non è stata toccata dalla macchia del Peccato Originale, mentre i peccatori sono condannati all'Inferno. In quegli anni ferveva una disputa fra Francescani e Domenicani sul momento in cui la Vergine Maria era stata esentata dal Peccato Originale. I Francescani erano Immaculisti, e sostenevano che la Vergine Maria era stata esentata dal Peccato Originale sin dal momento della sua concezione. La loro teoria sfociava nel Mariale di Bernardino dei Busti, una Messa e Ufficio della Immacolata Concezione, approvata dal Papa Sisto IV, un Francescano, nel 1480.

This iconography is interesting because it shows that the Virgin Mary was untouched by the stain of Original Sin, whereas the sinners were condemned to Hell. In those years there was a debate on the moment in which Mary had been exempted from the stain of Original Sin. The Franciscans were Immaculists and defended the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, the belief that Mary had been conceived free from Original Sin. This theory was embodied in the Mariale by Bernardino dei Busti, a Mass and Office of the Immaculate Conception approved by Pope Sixtus IV, a Franciscan, in 1480.

I Domenica i erano Maculisti, e sostenevano che la Vergine Maria era stata esentata dal Peccato Originale solo alla nascita, o al momento della Annunciazione./4

The Dominicans were Maculists, believing that Mary had been conceived in sin, and exempted from the stain of Original Sin only at birth, or at the moment of the Annunciation./4

Nel Messale di Sant'Egidio, Gherardo sembra sostenesse la tesi Maculista che la Vergine Maria sia stata esentata dal Peccato Originale al momento della Annunciazione.

In the Missal of Sant'Egidio Gherardo seems to have endorsed the Maculist theory that Mary was exempted from the stain of Original Sin only at the moment of the Annunciation.

mantenere 17 / 18/ La personalità di Gherardo é stata confusa con quella di suo fratello Monte (1448-1532/33), che non arriva all'altezza di Gherardo. Mostro qui una miniatura di Monte nel Salterio di Mattia Corvino, ora nella Biblioteca Laurenziana Plut. 15.17.c.2v. Angela Dillon Bussi ha mostrato che questo Salterio fu fatto per il patto di alleanza fra il Re di Ungheria Mattia Corvino e il Re di Francia Carlo VIII nel 1490, in occasione della guerra contro i Turchi che minacciavano Budapest./5 I due Re sono raffigurati insieme in piedi, con un volo di corvi neri in alto - emblema di Mattia Corvino, e un terzo personaggio giovanile ammantato di azzurro con i gigli d'oro di Francia, emblema di Carlo VIII. Il patto fra i due Re é raffigurato in un Salterio perché nel Salmo 2.2 é detto: 'Astiterunt Reges Terrae, et Principes Terrae convenerunt in unum' (Stettero in piedi i Re della terra, e i Principi del mondo si riunirono insieme), ad illustrare il patto. La scenografia é stupenda nel paesaggio che raffigurare l'assedio di Gerusalemme da parte dei Filistei, con David nel proscenio con il suo nome iscritto sul suo colletto. Ma manca la prospettiva aerea nel paesaggio, e manca lo sfumato nei volti che vedemmo in Gherardo. La scena non é bagnata di luce solare, e le figure sono piatte e sproporzionate. In manto rosso di Re David non ne modella il corpo e le tre figure in piedi sono sproporzionate dal ginoccio fino ai piedi, e sono malferme.

The attributions to Monte (1488-1532/33), Gherardo's brother, have been inextricably confused with Gherardo's. In my opinion the works of the two brothers differ and Monte's works do not come to the perfection of Gherardo's. For instance, the Psalter of Matthias Corvinus, now Plut. 15.17 of the Laurentian Library has been attributed to Gherardo and Monte jointly, whereas the illuminaton on fol. 2v is by Monte alone. The landscape is beautifully rendered. But it lacks Gherardo's aerial perspective and is not bathed in sunlight. The figures lack 'sfumato', are ill-proportioned and flat. David's red mantle does not model the figure and looks like a lacquer dish. Angela Dillon Bussi has rightly pointed out that this Psalter was made in 1490 to celebrate the alliance between Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, and Charles VIII, King of France, against the Turks who were menacing Budapest. /5 The illumination shows King David kneeling in prayer in the foreground, with his name inscribed on his collar. The siege of Jerusalem by the Philistines is shown in the right background, while at the left are shown, standing, King Matthias Corvinus, with a flight of crows on high - his emblem (crow='corvus' in Latin echoed in his name 'Corvinus') - and King Charles VIII, followed by a youth bearing the emblems of France - the blue mante covered with gold lilies. The two kings are shown in a Psalter because Psalm 2.2 states: 'Adstiterunt reges terrar et principes terrae convenerunt in unum' (The kings of the earth stood, and the princes of the world assembled together). Unfortunately, the figures of the two kings are ill-balanced and the portion of the body between knee and foot is too short. The scenery of Jerusalem's siege is, however, beautiful.

mantenere 17/ * 19/ Nel Cinquecento la miniatura fiorentina decade. Un miniatore molto alla moda, ma modesto e ripetitivo é Attavante (1452-1520/25), che visse a cavallo fra Quattrocento e Cinquecento. Mostro qui una sua miniatura eseguita per il Papa Leone X (Medici) fra il 1513 e il 1521 e ora nella Biblioteca Laurenziana, Plut. 18.3.c.13. E' il Simbolo del Papa S. Gregorio Magno. La miniatura mostra il titolo del libro su di una specie di tabernacolo sormontato da due puttini bianchi. La decorazione marginale mal si accorda con il tabernacolo.

The Florentine book-illumination of the sixteenth century is decadent. The beautiful harmony between text and illustration is lost in a hodge podge of elements. Attavante was a fashionable illuminator of the sixteenth century, but he repeats himself and his output is modest, as we may see in this Creed by St Gregory the Great illuminated for Pope Leo X (Medici), between 1513 and 1521, now in the Laurentian Library, Plut. 16.3, fol. 13. In the frontispiece the title of the book is inscribed on a sort of tabernacle surmounted by two small white 'putti. The border decoration ill matches the tabernacle.

mantenere 17/ * 20

Con la Trinità del Boccardino

(1460-1529) nel Cod. Inv.542.c.33v del Museo di S. Marco,

proveniente dalla Badia di Firenze, la pagina diventa un

guazzabuglio di elementi alla rinfusa. L'armonia della pagina,

così bella nel Quattrocento, ha perso la sua eleganza. La

ragione di questa decadenza non é solo l'avvento del libro a

stampa, ma é data maggiormente dalla situazione politica di

Firenze, con prima la cacciata dei Medici, poi la predica del

Savonarola, e finalmente l'assedio di Firenze del 1527.

Another illumination of the sixteenth century, by Boccardino (1460-1529) is even worse. It is a Trinity in a Psalter from the monastery of the Badia and now in the San Marco Museum in Florence, Ms. Inv. 542, fol. 33v. The various elements kill the page in a great confusion, and text and illustration vie with each other. This decadence is partly caused by the advent of the printed book, but mostly by the political situation in Florence with the expulsion of the Medici, the preaching of Savonarola, and the Siege of Florence, in 1527.

NOTE/ NOTES

1 Angela Dillon Bussi in Omaggio

al Beato Angelico, Cinisello Balsamo (Milano: Silvana

Editoriale, 2001), p. 33.

2 Angela Dillon Bussi, Ibid., pp.

30-35.

3 Angela Dillon Bussi, 'Alcune novità

sulla miniatura in età Laurenziana (a proposito di Littifredi

Corbizi, e di un nuovo codice per Lorenzo)', in Rara

Volumina , vol. I, 1994, pp. 15-16.

4 Mirella Levi D'Ancona, The

Immaculate Conception in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance

, published by the College Art Association of America in

conjunction with the Art Bulletin, New York, 1957.

5 Angela Dillon Bussi, Primo

Incontro Italo-Ungherese di Bibliotecari, Budapest, 2000,

pp. 51-53.

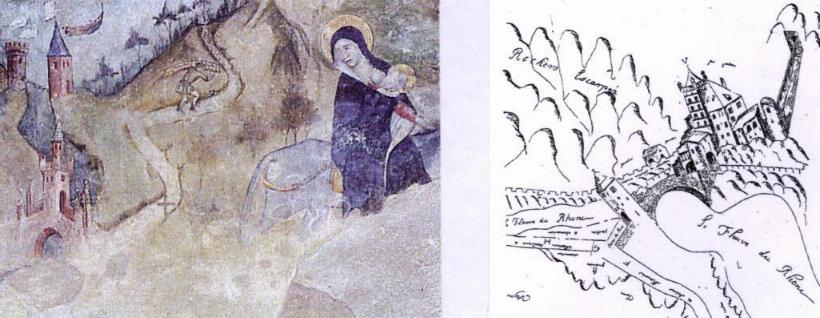

TAVOLA ROTONDA III: BRUNETTO

LATINO, IL TESORETTO, LI LIVRES DOU TRESOR, IL TESORO

THE ILLUSTRATION OF BRUNETTO LATINI'S TRESOR TO C. 1320

©ALISON STONES, UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH

Text Editions:

P. Chabaille, Li livres dou Tresor,

Paris, 1863 (based on Paris, BNF fr. 12581, MS F,

written in 1284, first redaction; descriptive catalogue of

manuscripts).

F.J. Carmody, ed. Brunetto Latini, Le Trésor,

Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1948 (based on Paris, BNF fr. 1110,

MS T, supplemented by Chantilly, Musée Condé 288, MS C5).

S. Baldwin and P.

Barrette, Brunetto

Latini, Li livres dou Tresor (Medieval and

Renaissance Texts and Studies 257), Tucson, AZ, 2003 (based on

Escorial L. II. 3, MS M3).

Other References:

M. Fauriel,

'Brunetto Latini,' in HLF XX 276-304.

F.J. Carmody, 'Brunetto

Latini's Trésor:

A Genealogy of 43 MSS,' Zeitschrift

für romanische Philologie 56, 1936, 93-99 and 60,

1940, 78-8.

id., 'The Revised Version of

Brunetto Latini's Trésor,' Italica 12, 1935, 146-47.

E. Brayer, 'Notice du manuscrit:

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, français 1109,' Mélanges dédiés à la mémoire de

Félix Grat, 2 vols. Paris, 1946-49, II, 237-40

(includes a list of manuscripts).

B. Ceva, Brunetto Latini, l'uomo e

l'opera, Milan and Naples, 1965.

P.M. Gathercole, 'Illuminations

of the manuscripts of Brunetto Latini,' Italica 43, 1966, 345-52

(generalized descriptions of BNF manuscripts only).

J.B. Holloway, Brunetto Latini: An Analytic

Bibliography (Research Bibliographies and Checklists

44) London, 1986.

F. Vielliard, 'La tradition

manuscrite du Livre dou

Trésor de Brunet Latin: Mise au point,' Romania 111, 1990, 141-52, adding

several previously unknown fragments.

Brigitte

Roux, L'iconographie

du Livre du trésor de Brunetto Latini (Thèse de

Doctorat, Université de Genève, 2004).

This Table was presented, in an earlier version,

at the Città e libro

II conference in Florence in September, 2002.

The manuscripts considered here mostly transmit the second redaction of the text, but Bolton-Holloway has criticised Carmody's division of manuscripts and the recension structure is more complicated than he allowed; his first redaction manuscripts considered here are F, F2, and K.

The manuscripts fall into three major stylistic groups and a cluster of stragglers:

1) Paris, BNF fr. 1110; Brussels, BR 10228; Vatican, lat. 3203, and, at some distance stylistically, Arras, BM182(1060). These are related to two Douai manuscripts, the martyrology of Notre-Dame-des-Prés, O. Cist., Valenciennes, BM 838 and the psalter-hours of Saint-Amé, OSB, Brussels, BR 9391; other secular books by this artist include several copies of the Estoire del saint Graal, Le Mans, MM 354, Paris, BNF fr. 770 (with other texts), and Paris, BNF fr. 342 (less close stylistically), written by a female scribe in 1274.

2) St Petersburg, SL Fr.F.v.III.4, London, BL YT 19, Paris, BNF fr. 567, and Florence, Laur. Ash. 125. These are associated with Thérouanne and close stylistically to the psalter-hours of Thérouanne, Paris, BNF fr. 1076 and Marseille BM 111, and Paris, BNF Smith-Lesouëf 20; there are also stylistic links to the missal of Saint-Nicaise, Reims, St Petersburg SL Lat.Q.v.I.78. They are also linked to other secular manuscripts centred upon the Lancelot-Grail, Paris, BNF fr. 95 and New Haven, Yale 229 and the four copies of the Roman d'Alexander in prose (see Ross and Stones in Scriptorium 2002).

3) Turin BN L.II. 18 (anc. ms. 1643), Geneva BPU Comites latentes 179, and Rennes, BM 593, are Parisian, but they are stylistically distinct. The Turin manuscript is by the Hospitaller Master and is datable between c. 1275 and 1291; the Rennes manuscript is part of a miscellany that was illustrated by the Thomas de Maubeuge painter and written in 1303 and 1304 by Robin Boutemont; the Geneva copy is also attributable to the early fourteenth century and is by an associate of the Maubeuge Master.

4) Paris BNF fr. 12581, written by Michel in 1284, is Champenois or perhaps Burgundian; Paris, BNF fr. 1109 and Lyon BM 948 are both associated with Arras, but by different artists: BNF fr. 1109 (written in 1310) by the Master of the Psalter-Hours of Arras, BNF lat. 1328, to whom may also be attributed a large number of other manuscripts. It is possible that New York, Morgan Library M 814 is also arrageois but its one miniature, depicting the author at his desk at the opening of Book I, is too rubbed for a certain attribution. Paris, BNF fr. 566, attributed to Liège (Oliver, Liège,1988, I, 187-89), is stylistically close to the Thomas de Cantimpré of 1295, Berlin, SB Ham. 114 and to the Lancelot-Grail manuscripts London, BL Add. 10292-4, Royal 14.E. III and Amsterdam, BPH 1/ Oxford, Bodl. Douce 215/Manchester, Rylands fr. 1, dating c. 1310-25 and made in the region of Saint-Omer or Ghent; the Liège association is based on the comparison with London, BL Stowe 17, a psalter of Maastricht use. Vat. Reg. lat. 1320 is by three artists, one Franco-Flemish, also associated with Ghent-Bruges production of the 1320s, and the other two Italian (designated a and b).

I leave aside here the four Southern French copies, London, BL Add. 30024, 30025, and Carpentras BI 269, perhaps from Perpignan; and Karlsruhe copy, Badische Landesbibliothek, MS 391, attributable to Toulouse. Oxford, Bodl. Douce 319, was probably made in Acre; Paris, BNF fr. 571, has been published as English, see L.F. Sandler, Gothic Manuscripts 1285-1385 (A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, V), London, 1986, no. 96; Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum 20, which contains only selections of the text as part of a miscellany, may be from Tournai.

Notes on the patterns of distribution and treatment of the illustrations follow below. Chapter Headings and Sigla are after Carmody.

General Observations:

There is no overall consistency

in the placing or choice of subjects for the

illustrations. Nevertheless, some patterns emerge:

--all manuscripts have an

opening illustration for Books 1 and 2, and all but F2 for

Book 3.

--all but the sparsely

illustrated Geneva have an illustration for Book 2, Ch. 50, On

Vices and Virtues.

--two manuscripts only, S and

A5, both Arrageois, omit an illustration for Book 1, Ch. 121,

Li mapemonde.

--at Book 1, Ch. 21, Second

Aage, there is alignment between the Arras Group (MSS T, B3,

R5, A6) and the Thérouanne Group (MSS L2, YT, L, Q2).

--Bestiary material is

illustrated in two manuscripts of the Thérouanne Group, L2 and

YT, and also in K and R3.

--Prophets and Saints are

illustrated only in L2 and K.

--Ages I-IV are most fully

illustrated in Q2.

For further comments, see BLatini120605-notes.html

Chapter Headings and Sigla after Carmody

[To fit on small computer

screen, reduce type size of Table to 8 point, instead of 10

point]

| Paris,

BNF fr. 1110 MS T |

Brussels,

BR 10228 MS B3 |

Vatican,

BAV lat. 3203 MS R5 |

Arras,

BM182

(1060) MS A6 |

St

Petersburg, SL Fr.F.v.III.4

MS L2 |

London,

BLYT 19

no

siglum |

Paris,

BNFfr. 567 MS L |

Florence, Laur.Ash. 125, ff. 1-139 MS Q2 |

Turin,

BNL.II. 18 anc. ms.1643)

MS T2 |

Rennes,

BM 593(147) ff.170-284 (1303-04) MS F2 |

Geneva, BPU Comites latentes 179 Geneva | Paris,BNF

fr.1109 (1310) MS S |

Lyon,

BM948, ff.3-93v MS A5 |

Paris,BNF fr. 566 MS K |

Vatican,

Reg.lat.1320 First redaction MS R3 |

|

| Table of Contents | 1-5 | 1-5 | iv verso-vii | 1-4 | 1-2r (2v blank) | 1-3 | i-xiv | 1-4v | 1-4 (4v-7v blank) | 1,3,4,5 | 1-4v | ||||

| Book I, Preface | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | i | 1 | 1 | 170 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 5 (French) |

| Chapter 6. Coment Dieus fist toutes coses au commencement | 4v | 7 | 5 | iii | 2v | 7 (Italian a) | |||||||||

| Chapter 19. Coment roi furent premierement | 5v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 21. Des coses ki furent au II. aage. | 13 | 13v | 8v | 7 | 11 | 10 | vii, vii verso | vii verso | 6 | 18, 18v | 11v (Italian a) | ||||

| Chapter 25. Des gens ki furent au III. aage | xiii | 7 | 20 | ||||||||||||

| Chapter 30. Dou regne des femes. | 13v | 8 | |||||||||||||

| Chapter 38. Coment Jules Cesar fu premier roi de Rome | 9 | 9v | |||||||||||||

| Chapter 39. Des rois de France. | 15 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 41. Des choses dou IV. aage. | 11 | 10v | 26 | ||||||||||||

| Chapter 42. Des choses ki furent el quint aage | 26 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 43. Dou sisime aage du siecle. | 26v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 44. De David ki fu rois des prophetes | 18v | 12 | 16v | 26v | |||||||||||

| Chapters 45-47. Dou roi Salemon son fil. Elyseus. | 17 | 27,27v,27v | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 48-50. Ysias, Jeremie, Ezechiel. | 17v | 28,28,28v | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 51-55. Daniel, Achias, Jagdo, Tobias, iii enfans profetes. | 18 | 28v,28v,28v | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 56-59. Esdras, Zorobabel, Hester, Judith | 18v | 29,29,29,29 | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 60-62. Zacharias, Machebeus, noviel loi. | 19 | 29v,29v,29v | |||||||||||||

| Chapter 63. Nouvel loi | 19 | 18 | xv | 12v | 29v | 19v (Italian a) | |||||||||

| Chapter 64. De la parente la mere Dieu. | 23 | 19v | 14v | 19v | 18v | xv verso | 15 | 21v | 30v | 20 (French) | |||||

| Chapters 65-67. De Nostre Dame Sainte Marie, S. Jehan Baptiste, S. Jake Alphei | 20 | 30v,31,31 | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 68-70. S. Jude, S. Jehan Evangeliste, S. Jakeme Zebedei. | 20v | 31,31v,31v | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 71-73. S. Piere, S. Pol, S. Andrieu | 21 | 32,32,32v | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 74-79. SS. Phelippe, Thumas, Bartholemeu, Mathieu, Mathias, Luc | 21v | 32v, 32v, 33, 33, 33, 33 | |||||||||||||

| Chapters 80-84. SS. Symon, Marc, Barnabe, Tymothe, Thithus. | 22 | 33v, 33v, 33v 33v, 33v | |||||||||||||

| Chapter 85. Encore dou Novel Testament et des .x. commandemens de la loi. | 33v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 86. Coment loys fu comenchie | 22v | 21v | xviii | 34 | 23 (Italian a) | ||||||||||

| Chapter 87. Coment Crestientés essaucha au tens Silvestre. | 26 | 22v | 36 | ||||||||||||

| Chapter 88. Coment eglise essaucha | 16 | 37v | |||||||||||||

| Chapter 89. Coment li rois de France fu empereor de Rome. | 38v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 90. Coment li empereor de Rome revient as Ytaliens | 18 | 24 | 23 | xx | 24v (Italian a) | ||||||||||

| Chapter 93. Coment l'empire vint as Alemans | 41 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 95. De la hautece Frederik | 16v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 96. De l'empereor et del pape Innocens | 21v | 26v | 26 | xxii verso | 27v (Italian a) | ||||||||||

| Chapter 98. Coment et por coi l'empereor fu desposes Manfred | 27v | 27 | xxiii verso | 28v (French) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 99. La nature est chose establi par iiii complexions | 28v | 22v | 28v | 28 | xxiiii verso | 19 | 29v (Italian a) | ||||||||

| Chapters 100-103. Des vices, des iiii elemens, Del auironnement del air et dorbisdes vii planetes. | 45, 45v, 47v, 48 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 104. Del mondes reondes et des iiii elemens | 34v | 31v | 24 | 30v | 48,48v | ||||||||||

| Chapter 105. De la nature de l'eve | 20 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 106. De l'aire et de la pluie | 31v | 31v | xxviii | 33 (Italian a) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 110. Del firmament et des planetes. | 23 | 51v | |||||||||||||

| Chapter

116. Comment la lune enpronte sa lumiere del soleil et des eclipses |

41v | 39 | 28 | 52,52v | |||||||||||

| Chapter 121. Li mapemonde | 38v | 44v | 42v | 31 | 38v | 40 | xxxvi | 27v | 42v | 193 | 36v | 56v | 41 (Italian a) | ||

| Chapter 125. comment hom ki est sages doit esliere tiere gaaignable | 35 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 130, 131. poissons, anguille, echinus, corcorel | 45v | 53 | 51v | 37v | 46 | 48,48v | 52 | 66 | 49,49v (Italian b) | ||||||

| Chapters 132-4. cete, coquille, delfin | 46v | 49v-50 | 66, 66v, 67, 67v, 67v | 50-50v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 135-6. ypotamie, sieraine. | 47 | 50 | 45 | 68,68 | 51 (Italian b) | ||||||||||

| Chapter 137. serpens | 47v | 50 | 202 | 55 | 68v | 51 (Italian b) | |||||||||

| Chapters 138-41. aspide, anfemeine, basilike, dragon | 48 | 51v | 69, 69v, 69v, 69v | 51v-52 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 142-4. scitalis, vipre, lisarde | 48v | 52 | 69v,70,70,70 | 52v(Italian-b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter145-6. aigle, ostoire | 49 | 52v,53 | 70v, 70v, 71 | 53 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 148. esperviers | 50 | 53v | 72 | 54 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 149,150. faucons, esmerillons | 50v | 54v | 72v,73 | 55,55v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 151-4. alcion, ardea, anes et oes, besenes | 52 | 55 | 73, 73, 73v, 73v | 55v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 155-68. calandre, peredrix, papegal | 52 | 56 | 74v, 74v, 74v | 56v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 169. paon | 52 | 56v | 75, 75, 75, 76, 76, 76v, 77, 77, 77, 77v 57(Italian-b) | 57 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 170-3. tortrele, ostrisse, co | 52v | 56v.57 | 77v, 78, 78, 78, 78, 78v | 57 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 174. lion. | 60 | 53 | 57 | li | 65 | 205 | 78v | 57v (Italian b) | |||||||

| Chapter 175. anteled | 53v | 58 | 79v 57v(Italian-b) | 57v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 176-7. asnes, bues | 54 | 58,58v | 80, 80 | 58v,59 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 178-80. brebis, belotes, chamel | 54v | 59 | 80v, 81, 81 | 59-59v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 181-3. castore, chevriers, cers | 55 | 59v,60 | 81v, 81v, 81v | 60 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 184. chiens | 55v | 60v | 82 | 60v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 185. camelion | 56 | 61 | 83v | 61v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 186. chevaus | 56v | 61v | 83v | 61v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 187. olifans | 57 | 62v | 85 | 62v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapter 188. formis | 57v | 63 | 86 63(Italian-b) | 63 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters

189-90. yena, loup |

58 | 63,63v | 86, 86v | 63,63v (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 191-4. lucrote, manticore, pantere, parandes | 58v | 64 | 87, 87, 87, 87v | 63v,64 (Italian b) | |||||||||||

| Chapters 195-6. singes, tigres | 59 | 64v | 87v, 87v, 88, 88, 88 | 64,64v (Italian a) | |||||||||||

| Book

2, Chapter 1. Des vices et des vertu |

58 | 67v | 66v | 48 | 59 | 65 | lvii | 44 | 74v | 210 | 62 | 57v | 35 | 89 | 64v (French) |

| Chapter 19. De force | 73v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter

28. Ci parole de justice |

66 | 55 | |||||||||||||

| Chapter

50. Li livres de moralités...les enseignement des vices et des vertus |

77 | 89v | 90v | 64v | 77 | 87 | lxxvii verso | 60 | 101 | 225v | 75 | 47 | 116 | 85 (Italian a) | |

| Chapter 68. De conoissance | 85v | lxxxvi verso | 94v (French) | ||||||||||||

| Chapter 69. L'ensegnement d'aprendre les nonsachans | 102 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 90. Ci dist de forche | 105 | 108v | 78 | ||||||||||||

| Chapter 95. Les enseignements de doner | 97v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 98. De religion | 100v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 115. Des biens de fortune | 106 | 121 | 126 | 91 | |||||||||||

| Book 3, Chapter 1. De bone parleure | 113v | 128v | 134v | 97 | 110v | 118v | 114v | 88 | 150v | 108 | 106v | 68v | 165 | 123 (French) | |

| Chapter 2.De retorike | 252v | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 33. Des vii vices dou prologue et premierement dou general Apres les vertus dou prologue | 140 | ||||||||||||||

| Chapter 54. De tous argumenz en ii manierez cest de loing et de pries Apres ce que li maistres ot enseignie les lieus | 151v | missing | |||||||||||||

| Chapter 73.Dou governement de cités | 137 | missing | 192 | 274v | 205, 218, 249 |

Notes

Table of Contents

K: f. 1 C, God creating birds and animals; God drawing Eve from Adam's side; f. 3 C, Three living (on horseback) and three dead ? (badly rubbed); C, Barlaam and Josaphat and Child in Tree; f. 5 C, Pelican in her Piety.

Book 1, Preface:

F: C, man sitting on top of money chest with coins on it, holding up a coin (f. 90v).

T: Scribe seated at desk, author as cleric standing before him, giving orders.

B3: Miniature in 2 columns: King orders 2 men, one of whom points to man holding bowl of golden objects (presenting or receiving ?), addressed by gatekeeper with huge key standing in door of central structure; on right, author seated at desk addressed by 3 lawyers one holding gloves; border: knight terminal with club and buckler; two men holding crook and long cutting instrument approach a bird of prey in a trap; another man gestures at them; knight terminal wields club, shield argent [white] three fesses coticed sable.

R5: Miniature in 2 columns: author seated at desk; group of men, one offering a goblet; men offering vessel full of coins to king; border: man in cale carries sack to windmill.

A6, YT: Author seated with a group of scholars, one of whom writes; YT border: birds, bagpiper on back of hybrid; bald hybrid archer; man playing rebec to dog; squirrel on goat chasing ape on unicorn.

L2: Author seated at desk between two groups of scholars to whom he points; border: foliate initial with hooded male terminal; male hybrid terminal, lion; bird and animal partly cut off; ape holding urine flask; greyhound running; man holding stag by its antlers and aiming a long arrow at it; shield or (device scraped off).

L: Author seated at desk with book, instructing one seated student holding book.

Q2: Author seated, standing man in academic costume.

T2: Miniature in 2 columns: Christ in Majesty, blessing, holding TO globe, in a mandorla with the evangelist symbols in the spandrels, flanked by two groups of 6 seated apostles, Peter holding key, Paul holding sword, the others without attribute.

Geneva: Author copying from a model.

F2: Seated author.

S, A5: miniature in 2 columns: 7 Days of Creation.

K: Wheel of Fortune; border: prophet holding scroll; hybrid trumpeting terminal.

R3: Author seated, standing man, both wearing academic hats, standing man pointing to the book in which the seated man writes; border: birds, hare, horned hybrid man holding a flail (?); running stag.

Chapter 6

A6: God warns Adam and Eve.

L2: Circular diagram of the universe containing planets and sun and moon, with Christ standing in hell-mouth at the centre; evangelist symbols holding scrolls in the corners of the miniature; bottom border: creation of Eve, drawn from the side of Adam; top: intertwined male and female hybrids with long necks and human heads.

YT: Circular diagram of the universe with the sun and moon; in the centre God and animals, Adam lying on the ground; border: bird, hybrids, knight riding.

L: God enthroned holding banner white a cross gules, between two angels, seated above the universe shown as circles with sun and moon prominent; bottom border, God and sleeping Adam.

Q2: Miniature in two registers: top: God blessing heaven with angels, sky with sun and moon, birds, animals, water with fish; bottom: creation of Eve, drawn from the side of Adam.

R3: God sits enthroned by rocks, trees, and water.

Chapter 19

Q2: Two kings, one holding gloves, stand before seated author who addresses them.

Chapter 21

T: Noah and family inside ark, Noah sends out dove.

B3: Noah and family inside ark, Noah sends out dove.

R5: Noah, wife and son look out of floating ark; Noah sends out dove.

A6: Noah and family inside floating ark, Noah sends out dove.

L2: Noah, between his family and the animals inside floating ark, sends out dove; hare playing gittern; trumpeter in robe party red and blue crouches on border; bottom: ape archer riding doe has shot arrow into rear of another ape, both turn back to look at each other.

YT: Noah and family inside floating ark with animals, Noah sends and receives dove; border: hybrid, female acrobat, naked woman with tail rides unicorn at dog hybrid.

L: f. 7 Noah and son building ark; f. 7v Noah and family with animals inside floating ark; female head in initial, dragon terminal.

Q2: Noah standing in ark holding adze.

K: f. 18 A, Adam digs, Eve spins and nurses; four seated figures at bottom of hill; f. 18v N, Noah, wearing academic hat in ark, animals entering.

R3: Noah and 2 animals in ark windows; raven on roof.

Chapter 25

L: Author ? Abraham ? wearing academic hat and group of men wearing Jew's hats; O, author's head in academic hat.

Q2: God in a cloud addresses Abraham on crutches wearing a Jewish hat.

K: Two women (one with veiled head, one wearing knotted headscarf) holding babies, Abraham seated holding stick, wearing Jewish hat.

Chapter 30

L2: Queen Penthesilea, seated, crowned by two ladies holding gloves; border, top: hybrid archer has shot arrow at male hybrid terminal; bottom: juggler holds up long table-top on his chin; woman dances and plays pipe and tabor.

Q2: Queen Penthesilea, seated, holding sceptre, ladies on either side; border: knight terminal holding sword and buckler.

Chapter 38

A6: Julius Caesar's army rides out (against Pompey).

Q2: Julius Caesar, crowned, seated, with his men: knight with raised sword, standing men.

Chapter 39

L2: King (Faremond ? Henri ? Gidebors ? Clyoedeus ? Nimorem ? identified as Clovis by Mokretsova, 95) crowned by two officials ; Q, bearded hybrid wearing hat; border, top: archer terminal has shot arrow into rear of male terminal; bottom: two shield or, traces of a device gules, scraped off.

Chapter 41

A6: Sacrifice of Isaac, angel stays sword, ram in background.

Q2: King Saul killed, King David crowned by mitred priest.

K: L, David crowned in presence of two groups of Jews.

Chapter 42

K: L, Captivity of the Jews.

Chapter 43

K: L, Birth of Christ: Virgin in bed, Child held by midwife, Joseph seated, wearing halo and Jew's hat.

Chapter 44

T: David slings at Goliath.

A6: David slings at Goliath.

L2: King David standing holding sceptre and book.

K: D, King David harping (Chapter numbers in K are one ahead of those in Carmody's edition).

Chapters 45-63

L2: ff. 17-19 contain a series of half-column miniatures of King Solomon followed by prophets in Jews' hats, holding scrolls; Isaiah holds a saw and a scroll; Daniel, bareheaded and haloed, holds his scroll in a crenellated pit with lions; Queen Esther stands with veiled head; Judith wears hair net, touret and head bands, slices off Holofernes' head in tent.

K: f. 27 S, Judgement of Solomon: two mothers, one soldier; ff. 27v-29v, a series of initials containing prophets holding scrolls.

Chapters 60-62

L2: Judas Maccabeus wearing knotted headscarf.

K: M, 5 Maccabees on horseback; O, seated scribe (evangelist ?).

Chapter 63

L2: Jesse in bed, surrounded by kingsÕ heads in circular branches of Tree, Virgin Mary in centre, holding palm; top border: hooded archer aims at rear of ape; bottom border: ape seated in scrollwork terminal; dog and rabbit in scrollwork terminal.

YT: Jesse in bed, surrounded by kingsÕ heads in circular branches, birds, Virgin Mary in centre, holding palm and crucifix; border: cat with mouse in jaw, archer terminal has shot bolt at bird, apes riding camels fight with swords and shields or.

L: Jesse (wearing academic hat) in bed, surrounded by kingsÕ heads in circular branches, birds, Virgin Mary in centre, holding palm and crucifix; A, male head wearing academic hat; top border: unicorn.

Q2: Christ on the cross between Ecclesia and Synagoga.

K: A, Baptism of Christ.

R3: Four foliate medallions flanking two foliate mandorlas, in two registers, each containing a bust except for the lower medallion which has Christ on the cross; in the adjacent roundels are the Virgin (right) and St John (left); one of the upper figures is female, all are indistinct.

Chapter 64

B3, R5: Nativity: Virgin lies head on hand.

A6: Jesse Tree: 4 roundels enclosing kings, 2 on each side of Virgin and Child in central lozenge.

L2: Bare-headed man and man in cale kneel one on each side of St Anne holding crowned Mary and Christ Child; border, top: archer has shot arrow at mouth of hooded black male hybrid; bottom: man playing portative organ; female acrobat; O, male head wearing Jew's hat.

YT: Esmeria holding Elizabeth facing St Anne holding crowned Mary and Christ Child; border: falconer and woman with dog beneath tree with birds, some goldfinches.

L: Man in blue vair-lined robe with red hood praying before St Anne holding crowned Mary and Christ Child; top border: naked man in hood, draped in cloak, aims spear at crouching unicorn; bottom: greyhound chases stag.

Q2: Moses and the Burning Bush: Moses, horned, holding Tablets, Head of God in bush.

T2: Annunciation to the Virgin.

K: C, Esmeria and Anne.

R3: Esmeria and Elizabeth with Anne and the Virgin Mary; border: birds, hybrid creature.

Chapters 65-67

L2: ff. 20-22: half-column miniatures with portraits of standing saints holding attributes or books, beginning with initial L, bust of Virgin Mary; unlike those in K, none are narrative in content.

K: L, Annunciation to the Virgin; E, execution of John the Baptist, Salome holding head on charger; A, torture of James Alpheus.

Chapters 68-70

K: I, Jude executed with axe; I, John the Evangelist boiled; I, James the Greater executed with sword.

Chapters 71-73

K: P, Peter crucified upside down; P, Paul executed with sword; A, Andrew roped to cross, looking down at crowd.

Chapters 74-79

K: P, Philip roped to cross and beaten; T, Thomas pierced through with lance, watched by seated crowd; B, Bartholomew flayed by 2 men, his lower body decorously draped; 2 Ms, Matthew and Mathias executed by sword; L, Luke seated writing on scroll, ox holding scroll behind him.

Chapters 80-84

K: S, Simon roped sideways to cross; M, Mark seated writing, looking back at symbol; B, Barnabas preaching to seated crowd; T, Timothy seated; T, Titus destroying an idol on column.

Chapter 85

K: O, Ecclesia and Synagoga.

Chapter 86

L2: Gnadenstuhl Trinity (God the Father's face rubbed); C, bust of Christ, pointing at text; border, top (partly cut off): archer has shot arrow at eye of hooded hybrid; bottom: hooded hybrid in hat; two shields, or (devices gules erased).

YT: Gnadenstuhl Trinity (badly rubbed); border: mastiff attacks hare; bird of prey.

L: Adoration of the Magi: Virgin and Child each hold a flower; top border: hare, squirrel; bottom border: ape falconer.

K: C, Nativity of Christ, Child in manger with ox and ass.

R3: Adoration of the Magi, all kneeling, one with his feet outside the frame.

Chapter 87

B3, R5: Emperor Constantine and his men before Pope Silvester.

K: A, Transfiguration of Christ.

Chapter 88

Q2: Emperor Constantine V Copronymous taking the idols from the image-worshippers of Western Christendom to Constantinople and there breaking and burning them (cf. text of Ch. 89).

K: Composite page of Passion scenes, from the Entry to Jerusalem to Pentecost (Virgin Mary present).

Chapter 89

K: O, Pope hands small cross to kneeling emperor Charlemagne, large shield of France in background.

Chapter 90

A6: Seated emperor (Charlemagne ?), two standing knights.

L2: Pope crowns Charlemagne, in the presence of Archbishop Turpin (shield France a cross argent [white]), Roland (shield party, France impaling Empire), and Oliver (shield azure a bust of a woman [Virgin Mary ?]) (illustrating the previous chapter); top border: backturned archer-centaur has shot arrow through pursuing centaur; bottom border: male and female (wearing wimple and veil) hybrid terminals.

YT: Charlemagne (face rubbed), shield party France and Empire, kneels before pope (illustrating the previous chapter); border: hybrid cripple trumpeter wearing hood with bells; greyhound chasing stag; hybrid.

L: Mounted combat between two armies: shields or a double-headed eagle sable; gules a lion argent [white], barruly or and gules, a bend sable charged with cockle-shells argent [white]; others rubbed. E, King's head; top border: greyhound chases rabbits; bottom: female falconer.

R3: Pope crowns Charlemagne (feet outside frame), watched by 3 standing men.

Chapter 93

K: M, Two bishops crown emperor (one of the Ottos, illustrating Ch. 93, or Henry VI (r1190-97), illustrating Ch. 94), watched by the electors (Ch. 93).

Chapter 95

Q2: Knights kneel before cephalophore saint (relics of St Peter) in presence of Pope Gregory IX (1227-1241); Emperor Frederick II on horseback with his knights, riding to Rome to subjugate the pope.

Chapter 96

A6: Pope Innocent IV (1241-1253) in conical hat and 2 clerics address Emperor Frederick II and lawyer (excommunicating Frederick).

L2: Pope Innocent IV hands sealed letter to cleric (in which he excommunicates Frederick II); Emperor Frederick and a group of lawyers dispute; top border: shield or, device gules erased; bottom: boys on the shoulders of men aim lances at each other, holding shields or.

YT: Emperor Frederick and a lawyer dispute with two more lawyers (pope not shown); border: animals, bird, hybrid.

L: Emperor Frederick disputes with 3 lawyers and a bareheaded man; man kneels before enthroned Pope Innocent IV in conical hat; E, foliate initial; female and male hybrid terminals.

R3: Enthroned pope gestures towards group of men who sail away in a boat.

Chapter 98

L2: Group of lawyers debate; pope hands sealed letter to messenger with spear (Urban IV [1261-1264] summoning Charles d'Anjou to fight Manfred and take possession of his lands in Italy); border, top: hybrid in Jew's hat holds banner sable ? erased; hybrid; bottom: youths fight with swords and bucklers.

YT: Three lawyers debate before seated pope; border: hybrids, bird of prey.

L: Man in vair-lined hat and group of tonsured clerics address seated pope; O, female head wearing headbands; pope's head terminal; top border: male hybrid; bottom: youth has shot stork with arrow.

R3: Pope Innocent IV and his forces approach Manfred and his army; border: birds, hybrid.

Chapter 99

T: Two men in academic robes sitting on a bench and debating with each other.

A6: God stands facing circle of planets, water, and earth with tree and tower on it.

L2: Man in bed, doctor with flask, within concentric rings of four elements; border, top (partly cut off: ape traps bird with decoy on string; bottom: hooded apes riding stag and goat joust with lances, shields barruly argent and azure, a lion gules (Luxemburg rather than Lusignan ?), and or a lion gules (Holland).

YT: Man in bed, doctor holding flask, within concentric rings of water with fish, air, fire; border: greyhound chases stag; bird; hare; huntsman on horse holding lure.

L: Doctor holds up flask before naked man lying in garden within concentric rings of water with fish, air, fire; dragon terminals; man holding portative organ, man (in kneeling position) riding on ox, holding axe.

Q2: Doctor holds up flask before naked man lying in garden within concentric rings of water with fish, air, fire.

R3: Four elements in medallions, air containing a flying bird.

Chapters 100-102

K: Marginal circle diagrams of elements, inscribed; waters, inscribed; air and fire, inscribed; planets, inscribed.

Chapter 104

B3, R5, A6: Circular diagram of 7 planets and sun with earth and a crenellated building at the centre.

L2: Circular diagram of 4 elements, at centre cleric seated at desk with book looks up (holding small telescope ?); border, top: knight terminal has struck dragon through the jaw with sword; female hybrid terminal; acrobat holding his feet with his hands, knives falling into a large jug; bottom: knight terminal holding sword, buckler, and lance with pennant or, aiming at snail.

K: marginal circle diagram of planets with earth at centre containing animal head spuing forth flames; f. 48v marginal circle diagram of planets accompanying text numbered ch. 105, on Saturn and the firmament.

Chapter 105

Q2: Circular diagram, seated man surrounded by water.

Chapter 106

L2: Circular diagram of 4

elements, at centre cleric seated at desk holding long wavy

rod which extends up through all four elements; border, top:

archer (partly cut off) aims at hares; bottom: cleric hybrid

faces female hybrid with veiled head.

YT: Circular diagram of 4 elements, man in academic hat sits in centre before open book, holding long wavy rod which extends up through all four elements; border: knight (shield, ailette banner or a cross gules) fights hybrid.

L: Circular diagram of 4 elements, man in academic hat sits in centre before open book, raising hand; behind him a huge gold sun extends over all four elements; L, king's head; border: male hybrid.

R3: Square diagram of the 4 elements, arranged diagonally in a mandorla-shaped configuration from bottom left to top right.

Chapter 110

Q2: Circular diagram of planets.

K: Marginal circle diagram of planets and zodiacs, inscribed.

Chapter 116

B3, R5: Circular diagram of 7 planets, sun and moon, with earth and a castle with 2 turrets at centre.

A6 Circular diagram with earth and a castle with single turret at centre, 2 suns and 2 moons, day and night.

K: Chapter numbered 111: diagram in text column of planets and eclipse; f. 52v chapter numbered 112: circle diagram of path of moon.

Chapter 121

T, B3: Circular diagram with earth and castle at centre, showing sun and moon, day and night.

A6: Earth with tree, building, water beneath.

R5: Man with pack on back standing by river and building (cf. Ch. 130, B3).

L2: Circular diagram of 4 elements, sun, moon, and planets, lions and trees at centre; border, top: hybrids; bottom: hooded archer blows horn, rides after greyhound chasing boar.

YT: Circular diagram of 4 elements with sun and moon in a fifth outer ring, house and trees at centre; border: hybrids; man shielding himself from the sun with a huge hat on a stick

L: Circular diagram of 4 elements and five rings of stars and planets on which are placed a large gold sun and a smaller grey moon; rocks in centre; hybrid terminals; top border: male hybrid.

Q2: Circular diagram of 4 elements and five rings of stars and planets, seated man in centre, holding globe.

T2: God stands holding a circular diagram of the world, a TO globe with water and earth.

F2: Two standing masters, one holding very long gloves.

Geneva CL: Circular diagram of the world with Jerusalem at the centre, framed by 8 heads representing the winds.

K: L, Circular diagram in two registers: top: two groups of castles linked by rivers (?); below, a cynocephalus (?) and a sciapod shielding himself from the sun.

R3: Circular diagram of the world shown as a spoon-shaped configuration linked across turbulent air by a 'handle' to the outer bands of water and fire.

Chapter 125

A6: Man digging outside house by tree.

Chapter 130: The Bestiary section mostly presents the fish, birds, and animals as 'portraits': I note here those that include narrative elements.

T: Water with a single large fish, and land.

B3: Man with cloth on stick over shoulder walks by water towards house (cf. Ch. 121, R5).

R5: Knights at sea in a sail-boat.

A6: Fish in water, earth with dragon and rabbits looking out of holes.

L2: Half-column miniatures of fish.

YT: Half-column images of fish.

T2: Miniature in 2 registers: 6 quadruped above, fish in water below.

K, numbered 125: P, merman, mermaid, and fish.

R3: Frameless coloured drawings of fish in three-quarters of a text column.

Chapter 132

L2: Man stepping out of boat onto land with trees on back of whale, slightly larger miniature; half-column miniatures of fish.

YT: Large miniature of whale with sailors on back; 3 small pictures of fish.

K, numbered 126: B, fish; f. 66v numbered 27, C, cocatrix emerging from side of crocodile which is swallowing it; f. 67 numbered 28: C, sailors lighting fire on back of whale; f. 67v numbered 129: C, coquille; numbered 130: D, man in boat next to 2 large flatfish (delphin).

Chapters 135-36

L2: 3 sirens play gittern, harp, trumpet; horse-like hypotamie with tusks.

Geneva: Sirens among fish in water.

K, numbered 131: Y, hypotamie, horse-like with tusks; numbered 132: D, sirens capturing sleeping men in boat.

Chapter 137

F2: Standing king and standing master disputing.

Geneva: 5 different creatures: serpent, aspide, anfemeine, basilisk, dragon.

K, numbered 133: S, 2 serpents with greyhound-like heads.

Chapters 138-41

L2: Asp bites leg of man.

K: numbered 134-137: A, man reading, asp at his feet; A, double-headed amphine; B, basilisk with cock's head; D, shaggy dragon.

Chapters 142-144

K, numbered 138-140 K adds Salamander as no. 141 to this group of creatures.

Chapters 145-146

K, numbered 142, 143: eagle flies to sun with small bird in claws; O, ostoire; f. 71 adds E, grand ostor, shown as falconer with bird on wrist.

Chapters 155-168

K numbered 152-165, shows fenix on flames, pelican in her piety.

Chapter 174

R5: Lion and trees.

L2: Miniature in two registers: lioness holding bone above lion; L, head of an old man, balding and bearded; border: top: female hybrid; bottom: bagpiper, hybrid, dancing woman in hair net; shield or a chevron gules (rubbed).

YT: Addorsed lion with bone, and lioness.

L: 3 crouching lions, superimposed; lion, lioness, and a second lioness eating large bone.

T2: Lion devouring animal leg, man with cloak on stick over shoulder walks away.

F2: Standing king and standing master: lion between them.

K numbered 171: L, cock chasing lion.

Chapter 175

K numbered 172: antelope speared by hunter in cale.

Chapter 181

L2: Trumpeting hunter holding lance; castor biting off testicles.

K numbered 178: Castor biting off testicles, hunted by man in cale with club.

Chapter 187

L2: Elephant with castle containing 3 knights in crenellations, knights in window.

K numbered 184: Elephant with castle on back.

Chapter 189

L2, YT: Hyena eating corpse.

K numbered 186: Hyenas lurking beside tomb.

Chapter 195

L2, YT: Hunter chasing ape carrying young on front and back; hunter (bareheaded in YT, hooded in L2) holding baby tiger drops mirror to tiger (amidst 6 mirrors in L2; 1 mirror in YT).

K numbered 192, 193: Hunter chasing ape carrying young on front and back; tiger amidst 6 mirrors, but no hunter or babies; numbered 194, 195, 196: taupe, unicorn in virgin's lap, speared by hunter; urs.

Book 2, Chapter 1

F: Q, tonsured author writing (f. 139v).

T: Author at desk expounding from book to standing cleric holding gloves and debating.

B3: Author writing; man walks away from door holding written manuscript.

R5: Author seated, writing on a scroll, a standing man before him.

A6: Author seated, two men before him, outside door of building.

L2: Author as cleric seated at desk, teaching seated students holding books; border: juggler in cale balancing sword on chin, holding a second sword; shields or a maunch sable (rubbed) and or a chevron gules (rubbed).

YT: Author (tonsured) teaching seated students who write; border: knight (shield azure a carbuncle or) aims lance at snail; archer has shot bolt at dragon terminal; lions, male terminal wearing hat. with bell, playing rebec; stag chased by dog.

L: Author in vair-lined academic hat enthroned between two groups of students, points to group on his right; arch frame with two mask-heads in spandrels; top border: youth's head terminal; bottom: greyhound chasing stag; male hybrid rebec-player wearing long pointed hood with bell terminal.

Q2: Author alone, writing at desk.

T2: Seated master before open book on lectern, 2 students seated on ground.

F2: Seated master before open book on lectern, students on ground.

Geneva: Q, author seated, writing.

S: author in hat seated at open book pointing to scales held by man in grey hooded robe; border: chaffinch.

Lyon: seated author at desk addressing group of standing men (lawyers ?).

K: Q, author in academic hat seated at desk with book instructs seated students; border: man embracing recoiling woman; equestrian knight (surcoat and housing bendy or and azure) aims crossbow at them.

R3: Bareheaded man standing and pointing at author who wears academic hat, and sits writing on scroll; border: hybrid.

Chapter 19

R5: Man with axe, two men with swords.

Chapter 28

T: Seated king, three standing men (badly rubbed).

A6: Seated king, group of men lead before him a man with rope around neck.

Chapter 50

T, A6, R5: Seated author, standing man holding gloves and debating.

B3: Author writing at desk, students standing before him.

L2: Author seated at desk, teaching seated students; border, top: bust-terminal blows two trumpets (partly cut off); bottom: male and female centaurs fight with lances, holding shields or a saltire gules a fess sable, and or a lion sable a bend gules (Flanders differenced).

YT: Author teaching seated students; border: knight (shield, banner, surcoat gules a fess or a star sable) aims lance at snail; greyhound chases hare; hybrids.

L: seated author, bareheaded, holding book, teaching standing students (badly rubbed): top border: hybrid eating human arm; bottom: male hybrid wearing conical hat.

Q2: Author alone, writing at desk.

T2: Author seated, teaching three seated students, all without books.

F2: Seated master, seated students on ground.

S: Author at desk pointing to man seated on ground before him; border: bird; faint marginal note beginning 'vn maistre...'.

K: A, man in cale and woman in wimple kneel before Christ on the cross.

R3: Outside a crenellated wall, two figures address a figure seated by a tree (rubbed).

Chapter 68

L2: Author wearing academic hat, seated at desk, instructing 3 standing men who gesture at him; border, top: affronted hybrids, bottom: ape falconer holding lure, hawk flying; ape bird-catcher holding owl on gloved hand; stork.

L: Author in vair-lined hat, seated at desk teaching seated students, one holding book; f. 87: border: lion, male terminal; bottom: male hybrid wearing pointed hat.

R3: Author in vair-lined hat and vair cape seated on bench discussing with bearded bareheaded man holding book; border: ape aiming spear at creature on foliage.

Chapter 69

R5: Seated King, standing men.

Chapter 90

B3: Samson carrying the gates of Gaza.

R5: Samson about to lift the gates of Gaza.

A6: Man in cale points at Samson carrying the gates of Gaza.

Chapter 95

T: Man at chest filled with coins, holds out chalice before 2 men holding gloves, one wearing a cale.

Chapter 98

T: Cleric kneels at altar with chalice beneath canopy (rubbed).

Chapter 115

T, B3, R5, A6: Wheel of Fortune.

Book 3, Chapter 1

F: A, tonsured master holding birch rod instructs seated students, one holding book (f. 191).

T: Seated king addresses 4 men.

R5: Author seated, writing.

A6: Standing king and man before 2 clerics.

L2: Master in academic hat seated at desk instructs seated students; border, top: hooded male bust; bottom: addorsed lions.

YT: Seated Master teaches seated students; border: hybrids.

L: Seated author in vair-lined hat at desk teaches seated students, one of whom holds book; f. 115 borders: male hybrids.

Q2: Author alone, writing at desk.

T2: Author and man seated together, debating; two other men stand behind.

Geneva: A, foliate initial.

S: seated master in hat pointing to man standing in pink robe holding gloves; marginal note in leadpoint, ending '...se main'.

K: A, bishop addresses seated ruler holding sceptre, both flanked by supporters.

R3: Author seated outside by tree, in three-quarter profile pointing to written text on desk (as though addressing the reader); border: hybrid, bird.

Chapter 2

F2: Seated king, two standing masters, one holding book.

Chapter 33

B3: Standing Master addresses group of standing men.

Chapter 54

B3: Seated Master holding book; 3 bareheaded academics address him.

Chapter 73

R5: Three knights ride to city.

T2: Seated king, his supporters on his right, addresses 3 men on his left.

F2: Tonsured cleric shows king a city.

K: numbered Book 4, chs. 1, 17, 51: f. 205 E, King

and bishop seated together, king flanked by knight in heraldic

robe quarterly 1 and 4 argent [white] a lion gules (Limburg),

2 and 3 sable a lion or (Brabant), the arms adopted by Jean I

de Brabant on acquiring the Duchy of Limburg in 1287; bishop

flanked by knight in heraldic robe barruly argent [white] and

azure, a lion gules overall (Luxemburg); f. 218 Government of

cities in peacetime: P, king holding sceptre seated between

standing man (poet ?) and musician playing rebec; f. 249

emperor wearing chain-mail and surcoat or an eagle sable,

holding sword, between 2 knights, one with surcoat or 3

besants voided sable, holding a club; the other in grey