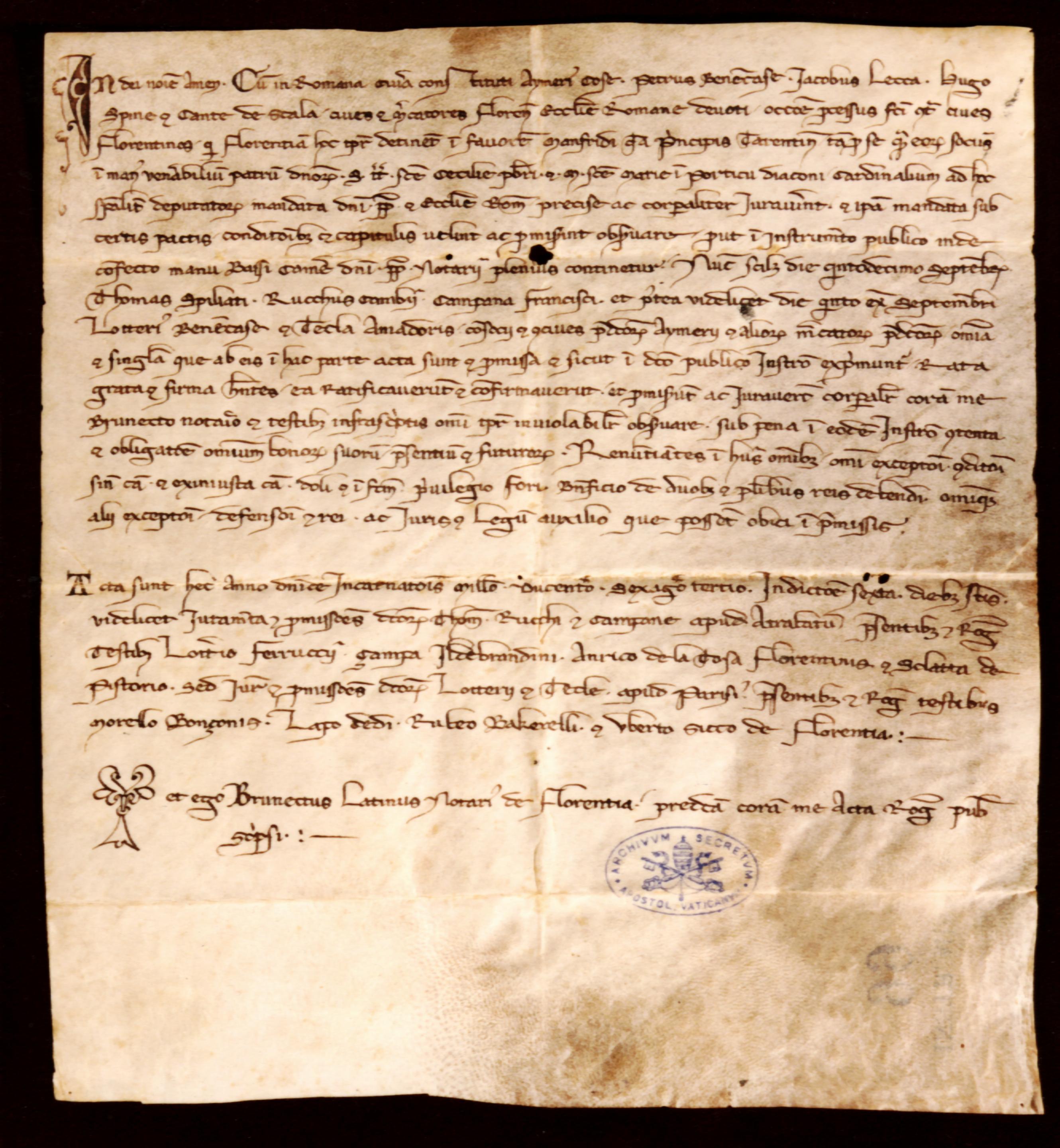

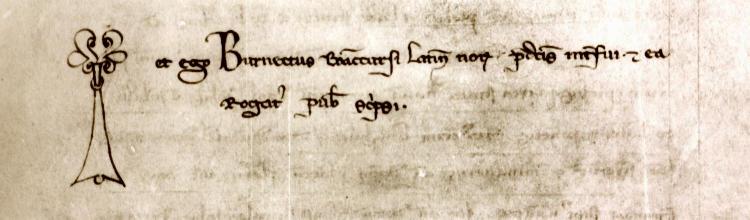

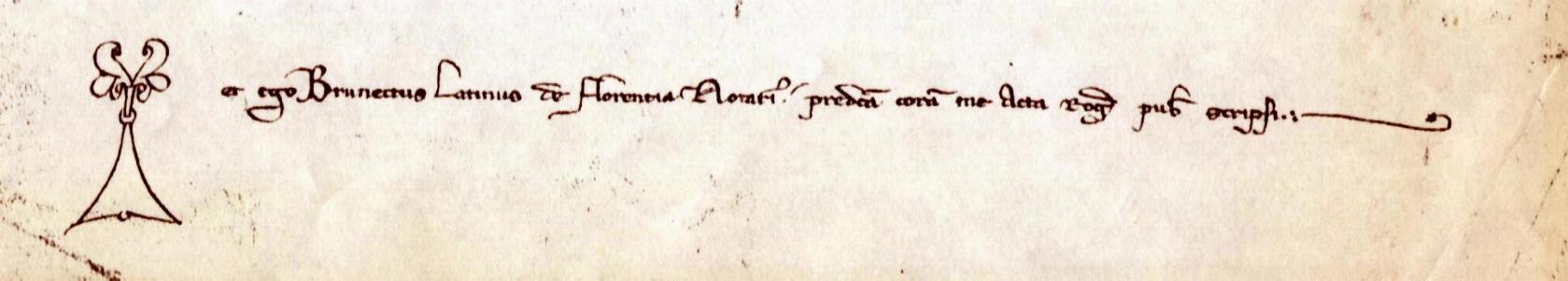

Vatican Secret Archives Autograph Document Written During Brunetto Latino's Exile from Florence

FLORIN WEBSITE © JULIA BOLTON

HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO

ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI,

& GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY ||

FLORENCE IN SEPIA ||

CITY

AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS I, II, III,

IV, V, VI,

VII || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA

MAZZEI' || EDITRICE

AUREO

ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA

WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES:

ITALIANO, ENGLISH || VITA

New: Dante vivo || White Silence

ELISABETTA SAYINER,

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA

{ Brunetto’s Tesoretto is a fictional journey. During this journey the protagonist, Brunetto, meets various teachers. While Brunetto learns from his teachers, the reader also learns with him. Brunetto, however, is not only the author and the protagonist of this didactic journey; he is also its narrator. The narrational “I” is that of Brunetto the protagonist after the conclusion of the journey.

Nel testo del Tesoretto, Brunetto è il nome dell’autore, del protagonista e del narratore. Quando Brunetto dà il proprio nome anche al narratore e al protagonista del Tesoretto, lui introduce il lettore a una complessa rappresentazione di se stesso che investe sia la realtà all’interno del poema che quella all’esterno. Questo saggio intende esplorare questa realtà e le dinamiche del narratore all’interno di questa realtà.

When Brunetto gives the poem’s protagonist and narrator his own name, he intertwines the various aspects of Brunetto - namely Brunetto the historical figure and poet, Brunetto the narrator, and Brunetto the protagonist— in a complex and subtle construction. This construction attempts to introduce the reader to an artificial and multi-layered alter ego that is highly controlled and manipulated. Brunetto’s programmatic self-representation in the text determines several aspects of his literary strategy and is at the heart of the author’s poetical effort. The aim of this paper is to explore some aspects of such construction, namely Brunetto’s self-representation in the dedication, his programmatic exploitation of some autobiographical references, and his skillful rewriting of the Boethian model.

In the poem, the voice of Brunetto undergoes some changes and is most meaningful at the beginning. In the dedication to the Worthy Lord (1-114), /1 the first person voice pleads for patronage and commends the poem. At the beginning of the narrative, the narrator introduces various facts about Florentine politics and Brunetto’s exile (114-85). As the allegorical journey begins (180-282), the centrality of the narrator weakens.

Nelle varie parti del poema la voce del narratore cambia. Prima nella dedica al Valente Signore (1-114) la voce di Brunetto chiede sostegno per il poeta e raccomanda il poema. Poi all’inizio della narrazione il narratore introduce le circostanze politiche e storiche dell’esilio di Brunetto (114-85). Tuttavia quando il viaggio allegorico comincia la centralità del narratore si affievolisce. Nei duemila versi che seguono il narratore scompare e la voce dell’autore si identifica con quello delle personificazioni che Brunetto incontra.

In the two thousand lines that follow the initial passage, political issues, historical references, and individual experience fade out of the text. The voice of Brunetto as narrator becomes more and more imprecise for the reader as the protagonist’s predominance in the text is displaced by a series of teachers who disclose to Brunetto the protagonist the knowledge that the author intends to convey to his reader. Thus, the authorial voice comes to be identified, in its didactic stance, not with Brunetto’s voice but rather with the voice of his mentors. The individual voice of Brunetto, however, emerges again in the garden of Love where the emotional experience of the poet becomes exemplary. There the text recovers the narratorial “I” that both the lyric and the didactic tradition employ for representing love. /2 The poet’s identity becomes again the center of attention, because personal experience is essential to affairs of the heart.

Even in the section where Brunetto is still the center of the poem, his voice displays different aspects. In the dedication to the Worthy Lord, (1-112) Brunetto’s voice is primarily that of the historical poet pleading for patronage. /3 However, this voice carefully and programmatically begins to shape the reader’s perception of Brunetto in the Tesoretto . The dedication can be divided in two parts. The first part (1-69) praises the Worthy Lord. Line 70 hinges the two parts together and names the author. The second part (71-112) commends the poem to the patron. This distribution of text magnifies the figure of the lord and gives minimal space to Brunetto, hinting at the extra-textual power relationship in which the lord is more dominant. Literally, the dedication is an act of homage to the lord from his intellectual servant and a pledge for financial support from a powerless and impoverished exile. Covertly, however, Brunetto manipulates the text in such a way that, in the end, he presents himself as an authoritative and powerful teacher, an essential asset for the lord, and a well-deserving recipient of a substantial remuneration.

Anche nella parte del poema dove la voce di Brunetto è più costante, troviamo notevoli variazioni. Infatti nella dedica del poema la voce del poeta è molto vicina al personaggio storico anche se incomincia già a dare forma alla figura che il poeta intende presentare al lettore. La dedica può essere divisa in due parti: i versi 1-69 lodano il Signore; i versi 71-112 gli raccomandano il poema. La distribuzione del testo dà più peso alla figura del Signore e indica l’autorità e il potere del Signore al di fuori del testo. Chiaramente la dedica è un omaggio che ha l’intento di chiedere supporto finanziario. Tuttavia un’attenta letture mostra che Brunetto sovverte questa rapporto di autorità e potere all’interno del testo.

Brunetto subverts the literary meaning of the text first of all through the naming of the author. The naming appears with a forceful rhyme “Come oro fino / Io, brunetto latino” [Just like refined gold: / I, Brunetto Latino] (69-70). Noteworthy in this couplet is the beginning of the line with “Io” followed by the full name of the author that occupies the entire line, making Brunetto’s presence in the text powerfully evident to the reader.

Vatican Secret Archives Autograph Document

Written During Brunetto Latino's Exile from Florence

While this rhyme sets up the definition of the lord as pure gold, it also undercuts it by juxtaposing the lord as gold to the name of the author. This contrast is the first hint of Brunetto’s argument concerning the pecuniary and transcendent value of the knowledge he is offering to the lord. This contrast also points to the difference between the lord and the author. The lord does not hold a treasure of knowledge but rather a treasure of gold, and he is defined as such. The author, on the contrary, does not hold any earthly riches but he owns a treasure of knowledge that he makes available to the lord by means of his book, namely the Tesoretto , the little treasure.

Questa cambio di prospettiva è attuato dal verso 70 dove l’autore si nomina: “Come oro fino / Io brunetto latino” (69-70). Nel primo verso la parola “fino” descrive il signore che viene identificato con l’oro stesso sia per il suo valore morale che, implicitamente, per la sua ricchezza. Tuttavia il secondo verso intruduce l’identità del poeta con grande forza, occupando l’intero verso e creando un constrasto o alternativa con quella del Signore. Brunetto sviluppa questo senso di opposizione nel poema presentando se stesso dapprima come alla mercè del potente e ricco Signore e poi come investito da potere, ricchezza e autorità. Il potere del poeta è quello conferitogli dalla sua sapienza e conoscenza e la sua autorità è quella conferitagli dal poema stesso. La ricchezza del poeta deriva dallo straordinario valore intellettuale e morale del poema che si traduce in valore pecuniario per la sua utilità didattica. In queto senso il poema e un “tesoretto,” cioè informazione che può essere tradotta il pratica. Per tanto il Signore possiede una ricchezza terrena e viene definito come “oro,” ma il poeta possiede la ricchezza trascendende della sapienza e della conoscenza che rende acessibile al Signore, condividendo con lui il suo piccolo tesoro.

Brunetto subverts the power relationship between the patron and the author also through the praising of the lord which follows some traditional topoi. /4 In fact, the praise of the lord continues with a set of comparisons between the lord and others that exemplify some specific virtuous characteristics (14-62). According to Brunetto, the lord’s sense and wisdom make him a new Solomon, he has the generosity of Alexander, the heroism of Achilles, Hector, Lancelot, Tristan, the oratory skills of Cicero, and the moral standards of Cato and Seneca.

Brunetto sovverte la relazione di potere tra il Signore e il poeta anche nel modo in cui loda il Signore (14-62). Lo definisce saggio come Salomone, generoso come Alessandro, eroico come Achille, Ettore, Lancellotto, Tristano. Gli attribuisce l’abilità oratoria di Cicerone e le qualità morali di Catone e Seneca. Questa lode è in molti aspetti tradizionale però è anche attentamente costruita per servire gli scopi dell’autore e per rappresentare il poeta come indispemsabile al Signore. Infatti, Achille, Ettore, Lancellotto e Tristano sono stati immortalati da poeti. Per essere Salomone o Cicero il Signore ha bisogno dell’aiuto di un esperto di legge e di retorica. Brunetto può essere tutto questo per il Signore.

Although this tribute flatters the lord, its focus is twofold: first it compliments the lord; second it sets up an authorial self-representation that will portray Brunetto as a worthy recipient of patronage and a necessary support for the lord’s leadership (113-62). In fact, Achilles, Hector, Lancelot, and Tristan owe their fame to poets. Alexander was a pupil of Aristotle, a philosopher. To be a new Solomon or a new Cicero, the lord would need help from a legal expert and a rhetorician: Brunetto can function in all these roles. Thus, the flattering introduction is an implicit promise of what the Tesoretto and his author can bring to the lord and how they can both intellectually enrich him and professionally serve him.

The author further strengthens his position by weaving into the text a biblical reference to heavenly versus earthly treasures. This reference echoes the Gospel according to Matthew, where Jesus urges his disciples not to lay up treasure on earth but in heaven: “Nolite thesaurizare vobis thesauros in terra: ubi aerego, et tinea demolitur: et ubi fures effidiunt, et furantur. Thesaurizate autem vobis thesauros in caelo, ubi neque aurego, neque tinea demolitur, et ubi fures non effodiunt, nec furantur” [ Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth where moth and rust consume and where thieves break in and steal; but store up for yourselves treasures in heaven where neither moth nor rust consumes and where thieves do not break in and steal] (Matthew, 6.19-20).

L’autore ulteriormente rinforza la sua posizione usando dei riferimenti biblici quando parla dell’opposizione tra tesori terrestri e tesori celesti. Qui fa riferimento ad un passo del Vangelo (Matteo 6,19-20) in cui Gesù ammonisce di cercare le ricchezze celesti e non quelle terrestri che sono caduche. Nel suo riferimento a questo passo del Vangelo, quando Brunetto parla delle ricchezze celesti modifica il significato del passo di Matteo. Infatti Matteo indente opere di fede mentre Brunetto indende l’incorruttibile ricchezza del sapere cioè l’incorruttibile ricchezza di ciò che viene presenato nel Tesoretto.

Through this allusion to the Gospel, Brunetto invites the lord not to seek earthly treasures and praises him for despising them, but to pursue and value incorruptible treasures. The author holds the imperishable treasure of knowledge, and he is willing to share it with the lord if he appreciates it. Brunetto writes: “E a voi faccio prego / Che lo teniate caro / E chenne siete avaro” [And to you I pray / That you may hold it dear / And be sparing with it] (84-86).

In spite of Brunetto’s dismissal of earthly treasures, his preoccupation with pecuniary matters is evident in the continuous insistence on money-related metaphors. For example, the book is a “Ricco tesoro / Che vale argento e oro” [Rich Treasure / Which is worth silver and gold] (75-76), of which one should be “greedy” (86). The text is comparable to “pietre preziose” [Precious gems] (90). Brunetto’s double rhetorical strategy dismisses the value of earthly things, and it measures the value of knowledge in pecuniary terms (gold, silver, and gems), while it points out to the patron that access to this treasury of knowledge must be compensated adequately.

The idea of proper compensation is reiterated in the second reference to the Gospel. This allusion points to a passage where Matthew writes that a Christian has to affirm, like the bright light of a candle, his faith in God: “[N]eque accendunt lucernam, et ponunt eam sub modio, sed super candelabrum, ut luceat omnibus qui in domo sunt. Sic luceat lux vestra coram hominibus: ut videant opera vestra bona et glorificent Patrem vestrum, qui in caelis est” [Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light onto all that are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in Heaven] (Matthew, 5.15-16). Brunetto, however, reinterprets this passage in didactic and practical terms to suggest that the Tesoretto is precious not only because it offers the incorruptible good of knowledge and wisdom, but also because the author’s didactic effort will make this knowledge accessible to the lord. Brunetto paraphrases the Gospel as follows:

Ben conoscho che’l bene[I know well that the good / Is worth less to him who holds it / All hidden in himself, / Than that which is revealed, / Just the way a candle / Shines less when concealed] (93-98).

Assai val meno, chi’l tene

Del tutto in sé celato,

Che quel ch’é palesato,

Sì come la candela

Luce meno, chi la cela

Un secondo esempio in cui Brunetto usa il testo evangelico per avvalorare il suo testo poetico si trova nei versi 93-98. In questo caso Brunetto fa riferimento al passo di Matteo in cui Gesù descrive una luce sotto un moggio (Matteo 5.15-16). Gesù dice che la fede dovrebbe esserre chiara ed evidente come una candela e non nascosta come una candela sotto un moggio. Quando Brunetto fa riferimento a questo passo ancora una volta ne manipola il significato. La luce della candela non è la fede, ma la conoscenze offerta nel Tesoretto. Questa sovrapposizione tra la fede e la conoscenza di Brunetto e tra il Vangelo e il poema investe di nuovo il testo di una autorità superiore e ne indica il valore trascendente e monetario.

Once again Brunetto uses an authoritative subtext to support his pledge. At the same time, he hints to a similarity between his text and the Good itself. Brunetto’s Good, however, is not faith but the knowledge he is offering.

After the conclusion of the dedication, Brunetto’s “I” undergoes a significant change. Here Brunetto narrates how and why he undertook his journey which let to encounter his teachers. In lines 114 to 162 the reader learns about Florence, Tuscany, and its civil war. This passage locates the beginning of the narration within the frame of Florentine history, giving it a distinctively political color:

Lo tesoro comincia,[The treasure begins, / At the time when Florence / Flourished and bore fruit, / So that she was of all / The Lady of Tuscany] (113-17).

Al tempo ke fiorença

Fioria e fece frutto,

Sí ch’ell’era del tutto

La donna di toscana

Later, Brunetto tells of his diplomatic trip to Spain and how on his way back to Italy he learns that the members of his party were exiled. Returning to Florence means for him prison and death. As the text makes the transition from the dedication to this autobiographical material, the voice of Brunetto undergoes a transformation from the historical self of the poet to primarily a first person narrator. In fact, even though this autobiographical material is historically true in many ways, this passage is the actual beginning of the narrative and merges the historical information with the fictional construction. In this transition between the dedication and the narrative Brunetto’s voice preserves its historical identity while it moves into the explicit literary model of the medieval didactic-allegorical journey, traditionally narrated in the first person. As a matter of fact, the allegory of the journey will emerge unequivocally from Florentine history and Brunetto’s exile, that is, from his personal and political experience.

Dopo la conclusione della dedica, l’”Io” di Brunetto cambia di nuovo quando incomincia a narrarre il viaggio del Tesoretto. Nei versi 114-62, il poeta incomincia a raccontare i fatti di Firenze e della Toscana, cioè della guerra civile. Dal panorama storico e politico Brunetto ci conduce alla sua storia personale e racconta del suo esilio da Firenze. La voce del narratore diventa più chiaramente una prima persona autobiografica che tipicamente si ritrova nelle narrative poetica di tipo allegorico-didattico. E’ importante notare che malgrado le informazioni su Firenze siano storicamente abbastanza corrette, l’informazione storica e autobiographica appartiene inequivocanilmente alla dimensione narrativa. Anzi, la narrazione del viaggio e gli incontri allegorici di Brunetto sbocciano direttamente ed esplicitamente dall’episodio dell’esilio.

Commonly, the model of the medieval allegorical journey used the autobiographical material to add a sense of authenticity to the narration, a perception of actuality and universality. On this issue, Segre writes:

Di solito, nei viaggi allegorico didattici medievali il materiale autobiografico dava un senso di autenticità e universalità alla narrazione. Si noti a questo riguardo Segre:

La forma pseudoautobiografica è una novità rispetto ai testi neolatini, sempre in terza persona. La prima persona, che prevarrà nei testi romanzi analoghi, è forse dedotta da quella delle visioni dell’altro mondo, che da questo tipo di presentazione traevano un effetto di reale . . . . Nei nostri testi naturalmente la prima persona non deve garantire la veridicità di quanto narrato, tant’é vero che viene subito corretta dall’opinabilità del sogno che poi rientra in una fortunata convenzione letteraria. La prima persona di questi viaggi ha un valore esemplare: io sta per tutti gli uomini, io é ognunoNotably, Segre talks about pseudo-autobiography because traditionally the author used minimal and often fictional autobiographical material. Brunetto, however, introduces relatively detailed and historically accurate information about himself and Florence. This makes the autobiographical section less conventional and more pragmatic. In fact, while on the one hand, in the Tesoretto, the information about Brunetto and Florence adds authenticity to the narrative and follows the traditional allegorical-didactic model, on the other hand, it introduces in the text a forceful historical, political, and personal dimension that defines Brunetto's historical figure in the eyes of his readers.

[The pseudo-autobiographical format is a novelty with regard to the neo-Latin texts, always in the third person. Probably, the first person, which will prevail in similar romance texts, is borrowed from visions of the under-world, which could obtain an effect of reality with this type of presentation. In our texts, obviously, the first person does not have to guarantee the truthfulness of the narration. This is immediately corrected by the disputability of the dream, which later becomes a self-sustaining literary convention. The first person in these journeys has an exemplary value: I is every man, I is everyone] (Cesare Segre, Fuori del mondo: I modelli nella follia e nelle immagini dell’aldilà [Torino: Einaudi, 1900], p. 53).

Si noti che Segre parla di pseudoautobiografia perchè tradizionalmente il materiale è minimo e spesso fittizio. Nel caso di Brunetto invece il materiale è corretto e relativamente esteso. Questo rende il suo materiale autobiografico meno convenzionale e più pragmatico. Infatti da una parte dà un senso di autenticità e rientra nella tradizione allegorico-didattica, ma dall’altra introduce nel testo una dimensione storica, politica e personale molto forte che ridefinisce la figura storica dell’autore nella percezione del lettore.

An example of how Brunetto programmatically manipulates his self-representation can be found in his references to Montaperti (159) which orchestrate Brunetto’s self-representation with a politically loaded stratagem. /5 In fact, Brunetto places his protagonist in Roncesvalles while he learns about his exile. Brunetto writes:

Venendo per la valle[Coming through the valley / Of the plain of Roncesvalles, / I met a scholar / And he courteously / Told me immediately / That the Guelphs of Florence, / Through ill fortune / And through the force of war, / Were exiled from that land, / And the penalty was great / Of imprisonment and death] (145-47, 155-62).

Del piano di Roncesvalle

Incontrai uno scolaio.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ed e’ cortesemente

Mi disse immantenente

Che guelfi di fiorença,

Per mala provedença

E per força di guerra,

Eran fori di terra

E’l dannaggio era forte

Di pregione e di morte

Historians and biographers of Brunetto have not yet been able to establish how Brunetto learned of his exile. The Tesoretto tells us that its protagonist learns about it from a Bolognese scholar in Roncesvalles. We have, however, a letter written by Brunetto’s father that seems to inform him of his exile. /6 Whether we decide that Brunetto’s meeting with the scholar in Roncesvalles is truth or fiction, we still need to establish the significance of Roncesvalles in the poem. To any medieval reader the mention of Roncesvalles would send a clear message. In the Song of Roland , the troops of Charlemagne, betrayed by Roland’s stepfather Ganelon and led by Roland, were defeated and wiped out at Roncesvalles. Roland’s heroic death during the battle triggered Charlemagne’s desire for revenge and ultimately caused the Christians’ conclusive victory.

Il riferimento a Roncesvalle è un chiaro esempio di come Brunetto manipola pragmaticamente la percezione del lettore. Brunetto racconta che il suo protagonista è a Roncesvalle quando viene a sapere del suo esilio (145-47 … 155-62). Storici e biografi non hanno ancora potuto stabilire come Brunetto sia venuto a sapere del suo esilio. Il Tesoretto ci dice che è venuto a saperlo da uno scolaro di Bologna, abbiamo tuttavia una lettera scritta dal padre di Brunetto che lo informa del fatto. Indipendentemente dalla fonte da cui Brunetto abbia saputo del suo esilio, il fatto che nel poema lo viene a sapere a Roncesvalle è molto significativo. Qualunque lettore medievale sentendo di Roncesvalle immediatamente non poteva che pensare a come le truppe di Carlo Magno, tradite dal patrigno di Rolando, abbiano sconfitto e distrutto i paladini cristiani. La morte eroica di Rolando in questa battaglia, spinse Carlo Magno a cercare vendetta e in ultima analisi ha ottenere la vittoria dei cristiani.

When Brunetto places his protagonist in Roncesvalles as he learns of the battle of Montaperti and his consequent exile, he sets up a distinctive parallel between the paladins’ defeat in Roncesvalles and the Guelphs’ defeat in Montaperti, that is, between Roland then and himself now. His party, like the Crusaders, was betrayed. The fight of Guelphs against the Ghibellines was not so much a struggle over control and power in Florence but here expressed as a crusade to defend the very roots of Christianity. The aim of this strife is to reappropriate what belongs by right to the Church: the Holy Land for the paladins and the Pope’s supremacy in Italy for the Guelphs. The “emperor” (perhaps the Worthy Lord is Alfonso el Sabio, King of Castile, and elected though uncrowned, Emperor) should seek revenge and justice if he wants to be the counterpart of Charlemagne. As for Brunetto, he appears as nothing short of a Christian hero, a crusader, who suffers martyrdom at the hands of the godless enemy. Martyrdom, however, is exile from Florence; the godless enemies are the Florentine Ghibellines; the conflict that resolves his fate is not in Roncesvalles but in Montaperti. /7

Quando Brunetto mette il suo protagonista a Roncesvalle quando sente della battaglia di Montaperti e del suo esilo, chiaramente costituisce un parallelo tra i paladini a Roncesvalle e i Guelfi a Montaperti. In questa luce, Brunetto presenta i Guelfi traditi come i paladini e la lotta tra i guelfi e i ghibellini non come una lotta civile per il controllo della città ma come una crociata per difendere la cristianità e la Chiesa.

Thus, Roncesvalles becomes the pivotal center of a political commentary, a propagandistic statement, and also a mean to reframe Brunetto’s personal history. As Brunetto is not simply one of the victims of a power-ridden civil war, he is the betrayed epic hero of an unfolding crusade. If the reader accepts Brunetto’s self-representation as truthful then he will feel compelled to embrace Brunetto in his strife and support him in his disgrace.

Quindi Roncesvalle diventa il fuoco di un’interpretazione politica, di un’affermazione propagandistica e di una riscrittura della storia personale di Brunetto. Perchè Brunetto non è tanto la vittima di una guerra civile tra fazioni assetate di potere, ma è l’eroe epico di una crociata, tradito e punito ingiustamente. Se il lettore accetta la rappresentazione che Brunetto ci dà di sè, allora deve unirsi a Brunetto nella sua lotta e sostenerlo nella sua disgrazia.

After having explored how Brunetto represents himself in the dedication and in the autobiographical section, it is important to observe how he represents himself as his character moves into a more literary and allegorical setting. As the character transitions, also the narrator does and begins to loose its central role. In fact, when Brunetto the protagonist hears about his exile from Florence, overwhelmed with sorrow, gets lost in the strange wood. The loss of his path initiates his allegorical experience. Brunetto’s narrator says:

Certo lo cor mi parte[Truly my heart broke / With so much sorrow, / Thinking on the great honor / And the rich power / That Florence is used to having / Almost through the whole world, / And I, in such anguish, / Thinking with head downcast, / Lost the great highway] (180-87).

Di cotanto dolore,

Pensando il gran honore

E la riccha potenza

Che suole aver fiorenza

E io in tal corrocto,

Pensando a capo chino,

Perdei il gran cammino

Dopo aver visto come Brunetto rappresenta se stesso nella dedica e nel segmento autobiografico. Passiamo ad osservare la sua autorappresentazione all’interno del contesto letterario e allegorico. Infatti Brunetto narratore e protagonista del passo autobiografico cambia quando la narrativa diviene più strettamente letteraria. Quando Brunetto sente del suo esilio viene preso da grande dolore e perde la via. Dal suo vagare emerge l’incontro con Natura (180-87). In questa transizione è marcata l’influenza della Consolazione della Filosofia di Boezio.

Here Brunetto evokes the Consolation of Philosophy. Elio Costa suggests that Brunetto derives from Boethius both topoi and rhetorical techniques (Brunetto 49-51). Costa believes also that the author intends to present Brunetto’s personal experience as similar to Boethius’ and therefore depicts Brunetto’s condition in Boethian terms: Brunetto, like Boethius, has suffered his punishment because of his political position, that is, both Boethius and Brunetto are virtuous politicians unjustly punished. One may add that both Brunetto and Boethius are “professional” politicians and philosophers who in a time of political misfortune turn to a didactic production. Within their works, this didactic production is for Brunetto and Boethius the outcome of the first-person protagonist’s encounter with a personification, and it explores the themes of Fortune and Virtue. Furthermore, Costa notices that the point where Brunetto is alluding to the Consolation coincides with Lady Philosophy’s invitation to abandon the muses of poetry for the muses of knowledge (Brunetto 216, n. 5). According to Costa, this suggests that Brunetto’s experience forces the protagonist to focus specifically on didactic writing rather than pursuing other poetical genres, as Brunetto may have done before his exile. /8

L’evocazio di questo testo è chiaramente riconosciuta dal Costa (Brunetto 49-51) il quale afferma che Brunetto rappresenta l’esperienza del suo protagonista in maniera del tutto simile a quella del personaggio di Boezio. Entrambi vengono ingiustamente puniti per motivi politici pur essendo uomini virtuosi. Entrambi vengono descritti come politici di professione e filosofi che si dedicano alla produzione didattica quando hanno perduto il loro potere politico. All’interno del testo Brunetto e Boezio sono protagonisti di vari incontri allegorici che esplorano tra gli altri i temi della Fortuna e della Virtù.

From this comparison between the Tesoretto and the Consolation , it emerges that both Brunetto and Boethius present their misfortune as essential to the production of the text. Exile for Brunetto, as it will be for Dante, is both a reversal of Fortune and a divine gift that leads to a unique knowledge. This knowledge renews the exile and entrusts him with an intellectual patrimony he feels compelled to share. Dante formulates this position openly while Brunetto implies it in the Tesoretto. Once shared, the experience of exile modifies not only the individual - the poet - but also, potentially, the community to which he returns. The wish to have an impact on their homeland is a constant preoccupation for both Brunetto and Dante as authors, who use political and literary means to reach out to Florence, to perpetuate their impact on their fatherland, and to bring their own presence within the wall of the city. Although physically removed from the city, Brunetto and Dante continually address their literary works and their political dealings towards the city, as if that remains an important moral, political, intellectual, and psychological stage.

Dal paragone tra Boezio e Brunetto emerge che entrambi rappresentano la loro disgrazia personale come il punto di partenza della loro esperienza didattica. L’esilio è per Brunetto un’esperienza cardinale che gli offre una comprensione priviligeta della realtà filosofica e morale che poi l’autore condivide con il lettore nel poema.Questa esperienza non solo modifica l’esiliato ma anche la comunità a cui ritorna. Brunetto infatti come Dante ha un continuo bisogno di essere in relazione con la città che ha abbandonato e usa la sua voce poetica per modificare la realtà da cui è rimosso. Un aspetto di questo sforzo è la riscrittura della propria rappresentazion che il poeta invia ai testimoni del suo esilio attraverso il testo poetico. Il testo poeto riporta l’esiliato nella prorio città e lo rende una presenza costante e potente. Allo stesso tempo il testo testimonia come la città rimanga il centro morale, politico, intellettuale e psicologoco per il poeta.

As Brunetto reaches out to the community of Florentines and of other influential Italians involved in the Florentine political dealings, he has multiple purposes. First he aims to establish himself as an authoritative teacher and a major intellectual figure of his time (as he represents himself in the dedication) so that he can establish himself again financially and professionally. Second, he wants his reader to see him as a martyr and a righteous man unjustly persecuted (like Roland and Boethius). So that the emperor or one of the great leaders of Europe - whom he was trying to rally against his enemies as an ambassador - would feel compelled to revenge him from his enemies. So that his Italian readership would feel compelled to embrace him and the citizens of Florence would allow him to return and restore him as a powerful and an influential member of their city. Brunetto, unlike Dante is going to be successful in shaping his fate. His literary works, especially the Trésor , gave him access to the court of Charles D’Anjou. And thanks to him, few years after the composition of the TesorettoBrunetto - admired, respected and powerful - will return to Florence.

Quando Brunetto si mette in contatto con la comunità

dei fiorentini e degli italiani ha varie scopi. Vuole prima di

tutto presentarsi a loro come un maestro di grande prestigio e

sapienza e come una figura di primo piano nel mondo

intellettuale europeo nella speranza che questo gli permetta

di riacquistare stabilità economica e professionale. Inoltre

vuole che il lettore lo veda come un martire e un uomo

ingiustamente perseguitato nella speranza che questi e che tra

questi i potenti d’Europa si sentano spinti a vendicare questa

ingiustizia e a schierasi con lui e i suoi. Quindi l’efficacia

e il successo del poema di Brunetto si potrebbe tradurre in un

risultato pratico. Cioè i suoi lettori e i cittadini di

Firenze in particolare si potrebbero sentire motivati a

sostenere Brunetto, a farlo ritornare in patria e a rendergli

prestigio e potere all’interno della città. Difatti Brunetto

grazie alla sua autorità letteraria e filosofica (specialmente

grazie al Trésor) entrerà a far parte della corte di Carlo

D’Angiò e grazie a lui, pochi anni dopo la composizione del

Tesoretto, Brunetto, ammirato, rispettato e potente ritornerà

a Firenze.

NOTES

1 Julia Bolton Holloway, Il

Tesoretto (The Little Treasure) (New York: Garland, 1981).

All the quotations and translations from the Tesoretto

are from this edition.

2 Leo Spitzer, “Notes on the Empiric

‘I’ in Medieval Authors” Traditio IV (1946) 414-22.

3 Although in the context of the

Florentine Commonwealth there is no strong tradition of requests

for patronage, many rulers, such as Charles V in France and

Robert the Wise in Italy, increasingly supported the production

of treatises on political and civic matters (See: Ruth Morse, Truth

and Convention in the Middle Ages. Rhetoric, Representation,

and Reality [ Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1991] 214).

4 In his detailed discussion of

traditional attributes and eulogies of heroes and rulers (Ernest

Robert Curtius, European Literature and the Latin Middle

Ages [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990]

176-82), Curtius mentions the topos of outdoing (162) which is

also pertinent to the Tesoretto : “Non avete pare / Né

in pace né in guerra” [You have no equal / Either in peace or

war] (4-5) and “A voi tutta la terra /. . . si convene” [To you

all the earth / Is rightly suited] (6-9).

5 Costa, however, reads this episode

as spiritually charged (Elio Gabriel Costa, “Brunetto Latini

between Boethius and Dante: the Tesoretto and the

Medieval Allegorical Tradition,” Diss.University of Toronto,

1974, 52). He first acknowledges that we have no proof that

Brunetto learned of his exile in Roncesvalles. He then adds that

Brunetto does not even seem to have a precise idea of the

location of the site of the battle. He suggests, however, that

Brunetto might have known of this location from literary and

historical sources or from having traveled by the actual place.

According to a legend, he adds, a chapel would mark the site

where the Christian heroes were buried. To support his spiritual

interpretation Costa points to a religious gloss of the battle

in the Chronique de Turpin and to the battle’s appearance

in church sculptures (52-53).

6 This letter was published first by

G. Ch. Gebauer ( Leben un denckwürdige Thaten Herrn Richards

erwählten römischen Kaisers [Leipzig: Gaspar Fritsch,

1744] 579) and then by D. Donati (“Lettere politche del XIII

sec.,” Bullettino Senese di Storia Patria III [1896]

230).

7 Thor Sundby ( Della vita e delle

opere di Brunetto Latini , trans. Rodolfo Renier,

[Firenze: Successori Le Monnier, 1884] 9-10) and Donati (222)

believe that the version presented in the Tesoretto is

not historically true. Bianca Ceva, on the contrary, believes

that the version of the Tesoretto is accurate, but that

Brunetto may have had the same information by various sources at

the same time (Brunetto Latini, l’uomo e le opere

[Milano: Ricciardi, 1965] 20). Julia Bolton Holloway suggests

that the letter is a scholastic exercise and that Brunetto

learned of his exile from the scholar in Roncesvalles (Brunetto

Latini: An Analytic Bibliography [London: Grant

&Cutler, 1986] 67). Some scholars even doubt the

authenticity of the letter. For example, Donati questions its

authenticity because of the highly literary way it is written

(228-29). In fact, he likens this letter to others written at

the time and describes them as follows: “la loro forma molto

artificiosa e prolissa rileva lo scopo puramente letterario e

scolastico di chi le compose” [Their highly artificial and

prolix form reveals the merely literary and didactic intent of

these who composed them] (228). This style led Donati to believe

that the letter did not have an informative purpose but was a

literary exercise: “non dubito di ritenere questo documento una

finzione, non solo per le ragioni stilistiche sopra accennate,

ma anche perchè appare strano che una lettera del tutto privata

potesse capitare nelle mani del maestro o notaio da cui fu

formata la nostra raccolta” [I do not doubt that this document

is fiction, not only because of the stylistic reasons I

mentioned above but also because it appears strange that a

completely private letter could end up in the hands of the

teacher or notary who prepared this collection of letters]

(229). Davidhson instead believes that Brunetto’ father wrote

this letter (Robert Davidsohn, Forschungen zur älteren

Geschichten von Florenz [Berlin: Mittler, 1908] IV, 149

and 153). Francesco Maggini ( La “Rettorica” italiana di

Brunetto Latini [Firenze: Galetti e Cocci, 1912] 18) and

Gianfranco Contini (Poeti del Duecento, vol. II [Milano:

Ricciardi, 1960] 169-172) also believe in the authenticity of

the letter.

8 Sundby (9) and others after him make

a reference to the chronicle of Brunetto’s contemporary

Ricordano Malespini (Storia fiorentina di Ricordano Malispini

col seguito di Giacotto Malispini dalla edificazione di

Firenze sino all’anno 1286, ridotta a miglior lezione e con

annotazioni illustrata da Vincenzo Follini [Firenze:

Stamperia di Niccolo Carli, 1816] 139) that Brunetto was already

in Florence or in its vicinity at the time, he received the

news. In fact, Malespini lists some prominent families that had

to leave Florence after Montaperti. In this list appears also

Brunetto and his family. It is noteworthy that Brunetto is the

only individual mentioned by name. With regard to Brunetto,

Malespini also stated that when the Guelphs were defeated at

Montaperti Brunetto’s diplomatic mission was completed. From

this, Sundby infers that by the time of the battle Brunetto had

just arrived in Florence and that he left it immediately after

the Guelphs’ defeat (9). Del Lungo, however, believes that this

interpretation is not accurate (“Alla biografia di ser Brunetto

Brunetto contributo di documenti per Isidoro del Lungo,” Della

vita e delle opere di Brunetto Latini [Firenze: Successori

Le Monnier, 1884] 212). For him, the reference to “Ser Brunetto

Latini” is a way to indicate his family and not him personally.

Peter Armour has gracefully shared with me that he considers

Malaspini an unreliable source.

9 Zannoni also refers to Malespini: “Il

Malaspini [sic] noverando le famiglie di questi fuggitivi per

sesti, giunto a quelle del sesto della porta del Duomo nomina

Ser Brunetto Latini e i suoi. E poichè, come sopra è detto,

quando avvenne la rotta di monte Aperti [sic] non era ancora

compiuta l’ambascieria, convien credere che Brunetto, il quale

uscì di patria con gli altri Guelfi, tornato vi fosse nel tempo

brevissimo, che corse da essa rotta alla partenza di loro”

[Malespini, counting the families of the fugitives according to

their neighborhood, having reached those of the neighborhood of

the Cathedral’s Gate, names Ser Brunetto Latini and his own. And

since, as I said before, when the defeat of Montaperti happened

his diplomatic visit [to Spain] was not completed yet, it is

suitable to believe that Brunetto, who left his homeland with

the other Guelphs, had returned during the very brief time that

passed between that defeat and their expatriation] (Il

Tesoretto e il Favoletto [Firenze: Giuseppe Molini, 1824]

XIII).

10 Zannoni points out that Brunetto may

have fictionalized in the text the episode of Roncesvalles just

as he fictionalized everything else. He writes:

Non dissimulo qui un passo del Tesoretto , nel quale asserisce il Latini, di aver avuto notizia della rotta di monte Aperti nel piano di Roncesvalle da uno scolaro che venia da Bologna, e di aver perduto per lo dolore di tanta disavventura il cammino, e d’essersi tenuto alla traversa d’una selva. Ma quale autorità potrà aver mai un poeta che finge di smarrirsi in una boscaglia e di ritrovare in sul vicin monte la Natura, che d’assai cose lo istruisce, a confronto d’uno storico, che visse nel medesimo tempo, che fu Guelfo, e che insieme con gli altri di sua parte uscì di Firenze?11 Morse’s following observation on truth and convention is particularly useful to illustrate the roots of my skepticism in assuming that Brunetto’s statement that he was in Roncesvalles is the truth: “The tension between correspondence to events which had actually, verifiably, occurred and the sophisticated convention of signs for their depiction reveals certain contradictions between what authors say they do, and what they do in practice. At the simple level ‘truth’ means something at least as much like ‘exemplary’ or ‘representative’ as it does ‘what really happened as far as it can be ascertained.’ ‘Evidence’ can be moral rather than actual. ‘Accuracy’ is one of a number of competing values and may be variously defined” (Ruth Morse, Truth and Convention in the Middle Ages. Rhetoric, Representation, and Reality [ Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991] 180).

[I do not deny here a passage on the Tesoretto in which Brunetto states that he had received the news of the defeat of Montaperti in the valley of Roncesvalles from a scholar from Bologna and also that he lost his path because of the sorrow of such a disgrace and proceeded on the right hand side of a wood. But what kind of authority could a poet ever have who pretends to get lost in a wood, find Natura on the top of a close by mountain, a figure who instructs him about quite a few things, as opposed to a historian who lived at the same time, who was a Guelph, and who together with the other members of his party had to leave Florence?] (XV).

VISUALIZING BRUNETTO LATINI'S TESORETTO IN EARLY TRECENTO FLORENCE

CATHERINE HARDING, UNIVERSITY OF VANCOUVER, CANADA

{ I n the course of the thirteenth- and fourteenth centuries, writers and readers were presented with a rapid multiplication of texts that required the invention of new visual imagery: the most famous examples in the Trecento are Dante’s Commedia and Boccaccio’s Decameron . /1 Our interest is heightened further when a text is illustrated rarely, or one time only. Such is the case with the only extant illustrated manuscript of Brunetto Latini’s Tesoretto (Florence, Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana, Strozzi 146) from the early Trecento./2 This particular exemplar features a cycle of imagery that was carefully planned in relation to the text. The interplay of words, illustrations, and initial lettering across the pages of Strozzi 146 is rich and complex, demonstrating that late medieval Italian readers were as adept as their northern European counterparts at negotiating the page with its ‘systemic rivalries’. /3

Strozzi 146 apparently belongs to a new type of book, the so-called ‘courtly reading book,’ which emerged in Italy during the thirteenth century. /4 Petrucci describes it accordingly: made of parchment, of careful manufacture and medium-small format (height between 230 and 240 mm), without any apparatus or commentary, and written in gotica textualis by a scribe of notably professional level. /5 Strozzi 146 shares all of these features; it is 243 mm high x 168 mm. The high legibility of gotica textualis has been associated with the emergence of silent reading practices for the lay reader in late medieval Italy. /6

It should be stated at the outset, however, that our labels for the many variations in illustrated Italian books of this period are rather imprecise, particularly when a key factor, that of relative systems of value, is introduced to the discussion. For example, Luisa Miglio describes the Specchio umano or Libro del Biadaiolo by the Florentine author and grain-merchant Domenico Lenzi, datable to the late 1330s, as a ‘deluxe, bourgeois’ book, because of its rather unusual mix of illustrations with heavy opaque color, one decorated initial, lists of grain prices, poetry and prose sections in a register-book format. /7 Since Strozzi 146 only possesses pen-and-ink drawings with traces of ink wash shading, would it be described as a deluxe or medium-cost book? One source, the record of the Perugian gabella [duty paid on goods brought into the city] of 1379, indicates that ‘books of Dante and the like’ were considered to be in a category of their own compared to the pricing of ecclesiastical, law or grammar books. /8 Once illustrations were added to Strozzi 146, the shift from unadorned to adorned page would have ensured that the book was prized in a variety of ways: as a work of moral and ethical instruction, as a literary work indicative of its author Brunetto Latini, as well as being a carefully produced illustrated exemplar that could be compared with other ‘grades’ of book in the household. /9

Petrucci links the emergence of the new categories of book with a new type of book-owner: he describes merchants and artisans who ‘bought [books] for themselves, preferring works in volgare of devotional-moral, literary-fantastic, rhetorical-historical, or even a technical nature’. /10 Strozzi 146 belongs to the category of didactic, moralizing literature written in volgare. Examples such as the Tesoretto or Specchio umano prompt us to reflect on key issues, such as public versus private reading, readers who briefly skim a text or read intensively (slowly, carefully, one book over and over), /11 and the corporate or shared use of books between one or more individuals. /12 Was an illustrated book like the Specchio umano designed to be shared in public, at Lenzi’s business table in Orsanmichele? The first framed image in the Specchio shows Lenzi writing at his business table, surrounded by his wares and the instruments of his profession. /13 Surely his book must have also contributed to the ennoblement of the author’s home and attested to his level of acculturation. It seems reasonable to assume that Strozzi 146 was commissioned to be used and displayed at home, simply because it fits most clearly into the category of book we imagine a reader contemplating in the private realm. Even if the evidence from this period is limited, we must continue to search for accurate definitions of ‘courtly reading’ books, or bourgeois books, as well as identifying the relative values of illustrated books, and the diverse ways that books functioned in Trecento society.

Brunetto’s current fame is linked primarily to his contributions to pre-humanistic politics and rhetoric, and as a model of the visionary poet for his ‘pupil’ Dante. /14 According to Charles Davis, Brunetto’s writings stressed the importance of education for the general public, and rhetorical education in particular for elite males running the affairs of urban centers like Florence. /15 The Tesoretto, the encyclopedic Trésor, and its volgare translation, the Tesoro, were designed to make knowledge appealing to laypeople. /16 Brunetto’s younger contemporary, Giovanni Villani, for instance, remembered him as: ‘a great philosopher and a consummate master of rhetoric....he was the master who first taught refinement to the Florentines...’. /17 The Tesoretto is written in simple rhyming couplets, and would have been relatively easy to memorize and recite. /18 The simplicity of the rhyme may explain why literary scholars relegate the Tesoretto to the less exalted category of didactic, ‘municipal’ literature, a category coined by Dante and still upheld in anthologies of Italian Trecento literature. /19 The poem presents an explanation of the nature of celestial and terrestial features of the cosmos, the necessity for moral and ethical training, penitence and conversion in a man’s life, the significance of an ongoing search for knowledge and self-development within the context of history. /20

Scholars point to the importance of the Tesoretto because it also demonstrates Brunetto’s interest in re-working the mode of allegory common in France during the 1260s. /21 Some of the major sources that he used in the Tesoretto and Trésor/Tesoro are: the Ethics of Aristotle; Cicero’s Offices and Laelius, (On Friendship) ; the Remedia amoris of Ovid; the Liber de Regimine Civitatum of Giovanni da Viterbo; Alain of Lille’s Anticlaudianus and De Planctu Naturae ; as well as the allegorical tradition of the Roman de la Rose. /22 According to Smith, scholarly evaluations of the poem suffer because of the tendency to compare it with the larger Trésor . He is adamant that the poem is not an abridged or even ‘surrogate’ encyclopedia, as some scholars suggest. /23 Literary scholars point out that Brunetto’s vision poem is filled with contrasts and ironies, and key epistemological questions: the poet’s journey presents the gradual enlightenment of the protagonist in natural and moral philosophy, in Christian virtue, and love. /24

The poem’s conclusion will be discussed in greater detail below, but Brunetto possibly intended to conclude the work with a treatise on the liberal arts, as suggested in the poem’s last few lines which trail off inconclusively. Brunetto’s use of the palinodic form at the end of the Tesoretto seems purposeful. Late medieval authors such as Uc de Saint Circ, Fra Guittone d’Arezzo, and Dante, all made use of the palinode as a form signaling their authorial decision to ‘sing again’, to recant, to retract their earlier thoughts on a particular subject, or to reflect an unfolding process of education’. /25 Scholars stress that the palinode is a rhetorical device, rather than a true expression of an author’s experience: the form works especially well for authors interested in establishing ‘an identification between author and first-person speaker...’. /26 Smith argues that Brunetto’s poem was conceived as a didactic work for the layperson, which ‘imposes limits on the range of his poetry and allegory, but as compensation ... [offers] a vision of a genuine sense of concrete historical reality, both in the ensenhamen and in the autobiographical presence of the author, who appears before us at a particular point in time and space’. /27 No one to date has noted how the palinode and its accompanying images contributes to the vivid sense of the author/self in the poem.

This study will examine how an illustrated book like Strozzi 146 fits into our existing knowledge of late medieval reading practices in Europe. The recent study by Kathryn Kerby-Fulton and Denise Despres demonstrates that some medieval texts were designed to be ‘performative, self-reflexive, and ...dissenting’. /28 I will be arguing here that the images in Strozzi 146 convey the idea of renovatio for a late medieval reader, in a pictorial vision that is forward-looking, questioning, self-perfective and performative. My study will examine how the overall structure of the cycle works to shape the reader’s movement through this one manuscript of the Tesoretto. Restrictions of space necessitate that I am only able to present the broad thematic structure of the poem, and note how key images within each part are visualized. The physical layout of Strozzi 146 exhibits a clear sense of the links between poetic-making visionary activity and the sense of a journey through the forms in the manuscript. From prologue to palinode, the visual images clearly heighten a reader’s experience of the text.

THE MANUSCRIPT

Strozzi 146 has been dated on paleographical grounds to the early fourteenth century; the visual evidence supports approximate dates of 1310 to 1325. /29 The artist of the manuscript is anonymous (dal Poggetto is the first to call him the Master of the Tesoretto ), with no other work by this artist having survived. /30 Although the figures display expressive, convincing poses and gestures, and the compositions possess a sense of monumentality, other features of the images, such as the confused handling of perspective, or places where the horses are drawn with less assurance, might suggest the work of a scribe-artist rather than a highly-trained professional. /31 The overall production of the manuscript would have been supervised by a director of a scriptorium, or a cartolaio who acted as an intermediary between patron and craftspeople. /32 The generic term ‘designer’ is used here to designate whoever was responsible for the overall production of Strozzi 146: the individual or team responsible for the final form of the manuscript clearly knew the poem exceptionally well.

The text of Strozzi 146 occupies the same space throughout the codex, 28-29 lines each in double columns, with generous margins left at the bottom of each page. Thus, the artist’s task was simplified considerably, for the images could be drawn on the available space left on each recto or verso, ensuring that close connections were made between text and image throughout the manuscript. The images themselves are simple shaded line drawings, with occasional traces of color, and without elaborate backdrops or decorated framing elements (they are surrounded in all but one case by rough double lines done in ink). /33 As a result of the simplicity of the images, the reader is presented with the essential shape of an episode, seen against the plain, empty space of the manuscript page, as if to ensure the meditative and mnemonic potential of the images.

The images appear to model a visionary ordinatio, emphasizing in particular the body of the poet and the motif of the journey of self-knowledge and discovery. The reader is asked at various points, both in the text and in the cycle of images, to contemplate certain ‘historical’ images, such as when Latini learns of the Guelf defeat at Montaperti in 1260, an event which resulted in his exile from Florence for six years. At other times, the reader must imagine a visionary, ‘abstract’ space, as when the Poet is being taught by Lady Nature. The performativity and self-reflexivity of the medieval reading process is made apparent in the way that the artist draws our attention to the ever-present body of the poet, Brunetto Latini, who appears in nearly every frame of the image cycle. Throughout the poem, the poet assumes a distinctive and repetitive set of bodily positions that seem to underscore his inbred sense of restraint, of moderation and moral goodness. /34 Read overall, the images convey an impression of the poet who is capable of operating within the realm of action, as when he encounters the realm of the Virtues, all the while exhibiting a deep sense of constancy and reserve. The manuscript seems to proclaim Latini’s excellence of mind and nobility of outward form. However, twice in the cycle, the gestures of his hands and arms ‘open up’: first when he is speaking with Ovid about love’s remedy, and then again at the end, when he meets Ptolemy on Mount Olympus. Perhaps because the poses and gestures of his body are so similar and so repetitive, allowing the reader to identify the poet, and by extension, stimulating the reader’s own internal reactions to the various questions raised by the central issues in the poem, these moments of bodily expansion and openness help to convey the notion of internal upheaval and conversion, as part of the poem’s allegorical process.

In emphasizing the performative aspect of this manuscript, I wish to draw attention to how the text, illustration and initial letters interact in the visual layout of the page. Runte’s work on the early manuscripts of Chrétien de Troyes demonstrates how initials, as structural markers, can shape the readings of these romances’. /35 No one to date has noticed how the layout of initials on the pages of Strozzi 146 work as ‘enabling’ dividers. At times they signal a shift in the dialogue between narrator and characters in the poem, or they may underscore an important point, and otherwise help to retain the reader’s attention throughout. It should be noted how frequently the initials are used to begin lines with simple connective phrases such as ‘and so’; ‘therefore’; ‘thus’, etc.. The irregularity of the textual divisions presented by the initials reminds us of the performativity of the reading process, at a time when readers used both oral and silent forms of reading and recitation. /36 The initials are clearly an important feature of the written page, providing places for a person to pause for breath in oral recitation, or perhaps reflect in silent meditative reading at significant places in the text — in short, to assist the active, hermeneutical dialogue of reading described so vividly by scholars such as Carruthers, Saenger, and more recently, Kerby-Fulton and Despres. /37

This manuscript offers us a chance to contemplate the intricate workings of memory and tradition, of remembrance and oblivion, for, as noted above, the Tesoretto was illustrated this one time only, although there are sixteen extant copies of the poem from the fourteenth- and fifteenth centuries. /38 In this sense, then, we might describe the imagery of Strozzi 146 as ‘dissenting’, based on the probable dating of the manuscript to the second decade of the fourteenth century. Could the focus on the poet’s noble body in this manuscript have been fashioned in response to some of the negative features of Dante’s portrait of Ser Brunetto in Inferno XV of the Commedia? /39 Francesco da Barberino alludes to the Inferno in his poetry, indicating that the first part of the Commedia was beginning to circulate in the second half of 1314. /40 A recent study reminds us that memory may enable new image production – indeed, images often precipitate, shape and consolidate memory: were there competing memories of this author, notary, and statesman abroad in Florence? /41 Until we are able to date Strozzi 146 with more precision, the idea that these images represent an alternative view of Brunetto Latini designed to counter Dante’s view of him in Inferno XV, remains mere speculation.

THEMES AND IMAGES

In studying comparative examples of texts with new visual imagery from the period, we observe a common difficulty: the identification of specific models employed by artists. Gillerman, for instance, maintains that the artists of various exemplars of the Commedia looked to contemporary monumental wall painting for ‘compositional formulae, iconographical types, ... [as well as] a narrative mode derived from late antique Roman sources’, such as the images found in the Vatican Virgil. /42 Dal Poggetto suggests that the images in Strozzi 146 were based on an earlier, now-lost prototype designed by Brunetto himself before his death in 1294, noting that some of the images appear to re-work patterns found in late thirteenth-century pictorial models. /43 Manuscripts of both the Commedia and the Tesoretto share certain elements: the use of a framed panel, limited stage space, how major elements are arranged in the scenes, the constant presence of the poet/ protagonist, and the quality of the rhetorical gestures. It is possible, as dal Poggetto indicates, that Strozzi 146 influenced the Florentine canon of imagery for the Commedia. The artist/ designer of our manuscript appears to have studied both miniatures and wall paintings ranging from the 1290s to the 1320s.

Within the overall cycle of image, we can designate certain sub-sets of pictures that demarcate the main themes of the poem. The images are clustered in the following way:

I. Prologue with author portrait and Brunetto’s embassy to the King of Spain (2).The idea of the journey is conveyed by the appearance and re-appearances of Ser Brunetto riding his horse, an action which occurs five times in the pictorial cycle; the poem mentions that he moves from Florence to Spain, from Roncesvalles to Montpellier, and finally, on to Mount Olympus.

II. Main Text with the message of exile (1); the poet’s journey to and including the meeting with Lady Nature (8); the poet continues on his journey (1); the court of the cardinal virtues (2); the encounter between the Poet, Knight and Largesse, Courtesy, Loyalty, and Valor (4); the court of Love (3).

III. Palinode with the poet and his friend (1); the friend meets Death (1), Ser Brunetto’s repentance (1); the journey resumes again and the poet meets Ptolemy (1).

Beginning with the prologue of the poem (lines 1-113), the textual unit is accompanied by two images on folios 1r and 1 v. On folio 1r we see the author-portrait of Brunetto Latini seated at his desk, inkpot and bound books lie scattered on its surface (figure 1). He passes a bound volume to another figure on the right. We sense immediately how the persons responsible for the manuscript’s visualization had to plan this first visual unit with care, following the traditional custom of employing an author portrait to assert the authorship and individuality of the text. In an important study of author-portraits within the manuscript tradition of the Roman de la Rose, Hult differentiates some of the different actions used to depict the authors of this romance: authors may be shown seated at a desk writing, following a venerable tradition based on representations of the biblical Evangelists; the author, or perhaps, a reader may be seated at a desk reading; two author/scribes may copy different manuscripts within the same frame; an author may read to a crowd; or an author may hand his book to another person. /44 Whereas some of the Rose manuscripts feature images of an author passing his book to another to underscore the continuity between Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun, here the idea of Brunetto as teacher of the Florentine people is highlighted. The idea of the author transmitting his book to the people is alluded to with the inclusion of the word ‘laicus’ beside the head of the person receiving the work. /45 This individual is shown in slightly smaller scale than Ser Brunetto, grasping the bound volume in his two hands. As befits the start of the prologue, line 1 features a decorated initial ‘ { A ’, which has been partitioned into colored patterns; the body of the poem relies on alternating red and blue letters that span two lines for major divisions of the poem. Apart from the first ‘A’ there are no other textual divisions of the prologue.

The next image depicts Ser Brunetto at the court of the King of Spain, an image which resonates closely with lines 70-75 of the prologue, ‘Io, burnetto latino/.../ a voi mi raccommando/ poi vi presento e mando questo ricco tesoro/ (I, Brunetto Latini, ..., to you I beg, then I present and send to you this rich Treasure)’ (figure 2). Interestingly, the book is not visualized here: rather, the artist depicts Latini on a diplomatic mission to Alfonso X, King of Spain, who is shown with his guard of honor: Latini has dismounted and gone down on bended knee, while a page holds his horse. The artist has also depicted the two most important figures in the scene, the King and the poet, in a larger scale than the two servants, a feature that will appear in many scenes throughout the cycle.

The text proper of the poem begins at line 114, folio 2r, with a two-line height blue ‘ L ’. On this page we are witness to Ser Brunetto’s moment when he learns of his exile from Florence. He is shown riding his horse and attended by a servant carrying his belongings; he learns of the disastrous turn of events from a scholar mounted on ‘the bay mule,’ a detail mentioned in the poem (figure 3). We must assume that the scholar is of some importance, for he is shown in the same scale as Ser Brunetto. However, the two men are distinguished by their different garments, and the presence of the servant behind Ser Brunetto may help to establish his social superiority.

The first division of the text proper of the poem occurs after thirty lines, starting at the opening initial ‘L’. The next large initial is a red ‘V’ , used to draw attention to the line announcing the poet’s journey through a valley near Navarre: ‘ V enendo per la valle/ del piano di roncisvalle/ (Coming through the valley of the plain of Roncesvalles).’ The next division, a letter ‘E’, occurs overleaf on folio 2r, and marks a moment of prophecy, which will find its resolution shortly, beginning at line 163: ‘ Ed io, ponendo cura/ tornai a la natura/ c’audivi dir che tene/ ongn’uom c’al mondo vene/ (And, becoming sorrowful, I returned to the nature that I have heard is possessed by every man coming into the world),’ an interior conversation that helps to foreshadow his conversation with Lady Nature. In accordance with the poem’s use of a specific point in time and space, the designer of the cycle apparently chose to set the first three images in historical time; the reader is reminded of the contemporary events of the poet’s biography, and the forces that have set the journey of self-discovery in motion.

The poem continues on for a further sixty-eight lines unmarked, and when the next large initial, an ‘O’, is used at line 230, it helps the reader return to the narrating voice of the poet: ‘ O nd’io ponendo mente/ All’ alto convenente/ (Therefore, I, considering the lofty dignity...).’ A further fifty-two lines takes us to a large initial ‘M’, this time to mark another moment requiring emphasis in the poem, at the moment when Lady Nature turns to look at the poet in line 283: ‘ M a poi ch’ella mi vide/ La sua cera che ride/ Inver’di me si volse/ (But after she saw me she turned toward me that smiling face).’ The narrative in this part of the poem also shifts from ‘real’ time to a focus on the poet’s internal state, which is full of affect, and in this, the pictures do not convey the complexity of Ser Brunetto’s interior state. He is described in line 186 as moving through the land full of anguish, thinking with head downcast: ‘E io in tal corrocto/ pensando a capo chino/ perdei il gran cammino/ e tenni a la traversa/ d’una selva diversa/ (And I, in such anguish, thinking with head downcast, lost the great highway and took the crossroad through a strange wood),’ to enter eventually into the world of Lady Nature. These moments of emotion and traveling are conveyed through the combined force of words and images: at the bottom of the page we see Ser Brunetto riding on his horse and raising his hands as if to indicate Lady Nature, who is seated at the right, resplendent amidst a ‘great crowd of different living things’ (figure 4). The image here is full of rich details, clearly inspired by Biblical imagery of creation, some of which are not mentioned in the poem: plants, fish, birds, animals, and humans, the sun, moon and starry realm shown behind her head. By folio 3v, we can see just how closely and carefully the artist has interpreted lines 236-240: ‘Ebbi proponimento/ di fare un ardimento/ per gire in sua presenca/ con dengna reverença/ (I firmly resolved to pluck up my courage to come into her presence with proper reverence).’ The artist conveys this notion of reverence and awe before Lady Nature: the poet is shown with his arms folded across the upper part of his chest. In all, six images in this section of the manuscript show the poet displaying his body and hands in various poses of reverence and awe before his instructress; she is always shown seated in a pose of great majesty.

We find a parallel use of the gesture of arms folded across the chest in monumental paintings of the early Trecento: Barasch reminds us that Giotto made effective use of the same motif in wall paintings, as in the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple at the Arena Chapel, or the Raising of Drusiana in the Peruzzi Chapel./46 He notes the connection of this gesture with the priest’s posture when receiving the Eucharist in early Christian times. The gesture apparently persisted through the ages, for a late twelfth-century didactic poem tells us that believers used it to indicate their need for repentance, humility and forgiveness. /47 The dominant impression of Ser Brunetto in this section is one of inward dignity and reverence, certainly not the conflicted representation of the damned sodomite found in Guido da Pisa’s illustrated Commentary on Dante’s Inferno, now in the Musée Condé, Chantilly, and analyzed recently by Camille. /48

In this part of the manuscript, both individuals employ hand gestures that indicate their response to one another: Lady Nature can carefully enumerate the points of a discussion, using her ‘speaking hands’, although it may be hard to know exactly what moment of speech is being represented (figures 4-11). /49 For instance, on folio 6v, her right hand gestures upwards towards the heavens (figure 8). As she does this, the poet falls on his knees. /50 Or, as on folio 10r, she spreads her arms open expansively to indicate the vastness of the ocean, with the Pillars of Hercules at the mouth of the Mediterranean (figure 10). In the final scene of this unit, the poet adopts a pose of proskynesis to kiss the feet of his lady, to underscore lines 1171-79 in the poem which state: ‘E io gecchitamente/ ricevetti il presente/ la’ nsengna che mi diede/ poi le lasciai lo piede/ e mercé le chiamai/ ch’ella m’avesse omai./ per suo accomandato/ (And I humbly received the present, the badge she gave to me, then I kissed her feet, and cried out for the mercy that she till now had shown me through her advice)’ (figure 11). The large initial letters in the rest of the dialogue with Lady Nature appear to be used when the reader/ Poet is addressed directly, as on folio 3v, ‘ A te dico (I say to you),’ or with coordinating conjunctions, as evidenced in the frequent use of: ‘ P oi (then)’;’ B en dico veramente (truly I say)’, to move the reader on through the poem.

We are reminded of the nature of the journey with the motif of the poet riding his horse set against the blank background of the parchment page (figure 12). The artist has not indicated anything of the background, perhaps because lines 1183-89 state ‘O r va mastro burnetto/ per lo cammino stretto/ cercando di vedere/ e toccare e sapere/ ciò ch’elgli é destinato/ e non fuit guari andato/ ch’i’ fui ne la diserta / (Now goes Master Brunetto, along the narrow path, seeking to see, and touch and know, what is destined for him. And I had not gone for long when I was in a desert).’ The visual sense of the emptiness of his movement in space is strengthened by the bleak words that follow in lines 1198-1200: ‘quivi nonn’a viaggio/ quivi nonn’a persone/ quivi nonn’a magione/ (There was no travel, there were no people, there was no dwelling). Again, the larger initials help the narrative flow and mark the reader’s identification with the poet-protagonist: they are found at line 1183: ‘ O r va mastro burnetto (Now goes Master Brunetto),’ and then again in line 1205 when we learn about his interior state: ‘ E io, pensando forte...(And I thinking hard).’

The next sequence is focused on Brunetto’s presence at the court of the cardinal virtues – the artist has created a double image in which the poet’s body is noticeably absent. We must turn from 12r to 12 verso to complete the reading of the cardinal virtues: the image shows Prudence in the center of the image, flanked by Virtue and Temperance, or Measure, then overleaf, the images of Fortitude and Justice (figures 13 and 14). The poet makes continual reference to his own action of seeing, as the field of vision shifts to encompass the next object of his attention, which begins on folio 13r: the witnessing of the conversations between the Knight and the four daughters of Justice: Largesse, Courtesy, Loyalty and Valor. He states in line 1365-67: ‘Ch’io vidi largheazza/ mostrar con gran pianezza/ ad un bel cavalero/ (I saw Generosity showing with great clarity to a handsome knight).’ The initials, too, underscore the poet’s actions, as in line 1263: ‘ E io c’avea volere (And I, who had the desire);’ line 1300: ‘ P oi vidi immantenente (Then I saw suddenly);’ or line 1305, ‘ E partendomi un poco (And parting a little).’

In these four scenes the poet acts rather like the figure of St John the Evangelist in Apocalypse manuscripts: he stands in a pose of reverence, with the same gestures of folding his arms across his chest in an attitude of devotion, or with his right arm raised in a rhetorical gesture that emphasizes his dignity. /51 The Knight stands beside him and receives instruction from the four enthroned figures of the virtues, all of whom look remarkably similar and suggest the use of the same pattern sheet on the artist’s part (figures 15-18). In the case of Largesse, Courtesy, Loyalty, the poses of the bodies are remarkably similar, and their hands seem to be raised in almost identical gestures of teaching or declamation. Valor, by contrast, carries her shield and mace (figure 18). The Knight moves through a series of bodily movements: from arms open and elbows down by his side, which is used twice, or, we see his arms folded across his chest, and finally, still with his arms held down by his side, holding his right hand near his heart and the left hand open. Even the Knight seems to share in the general gravity of the encounters. /52