APP - ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING’S

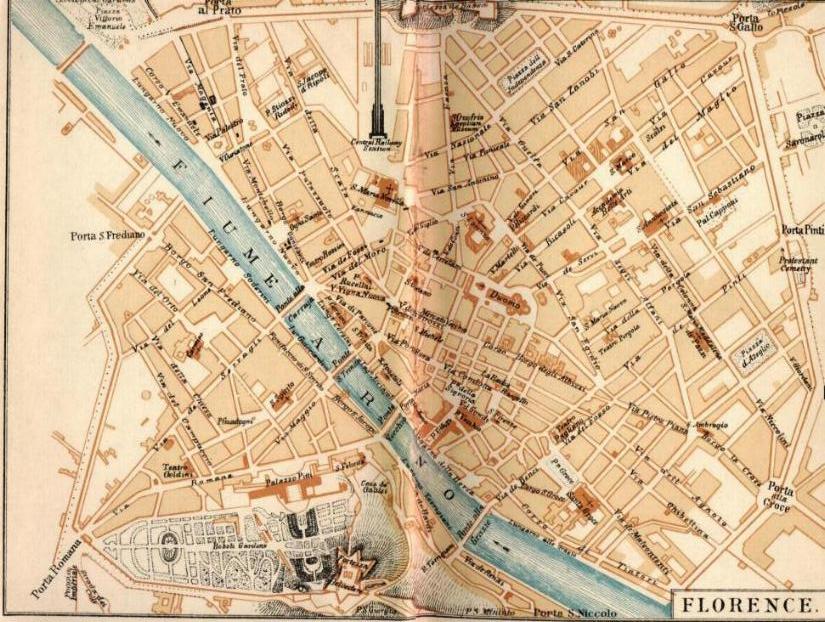

FLORENCE

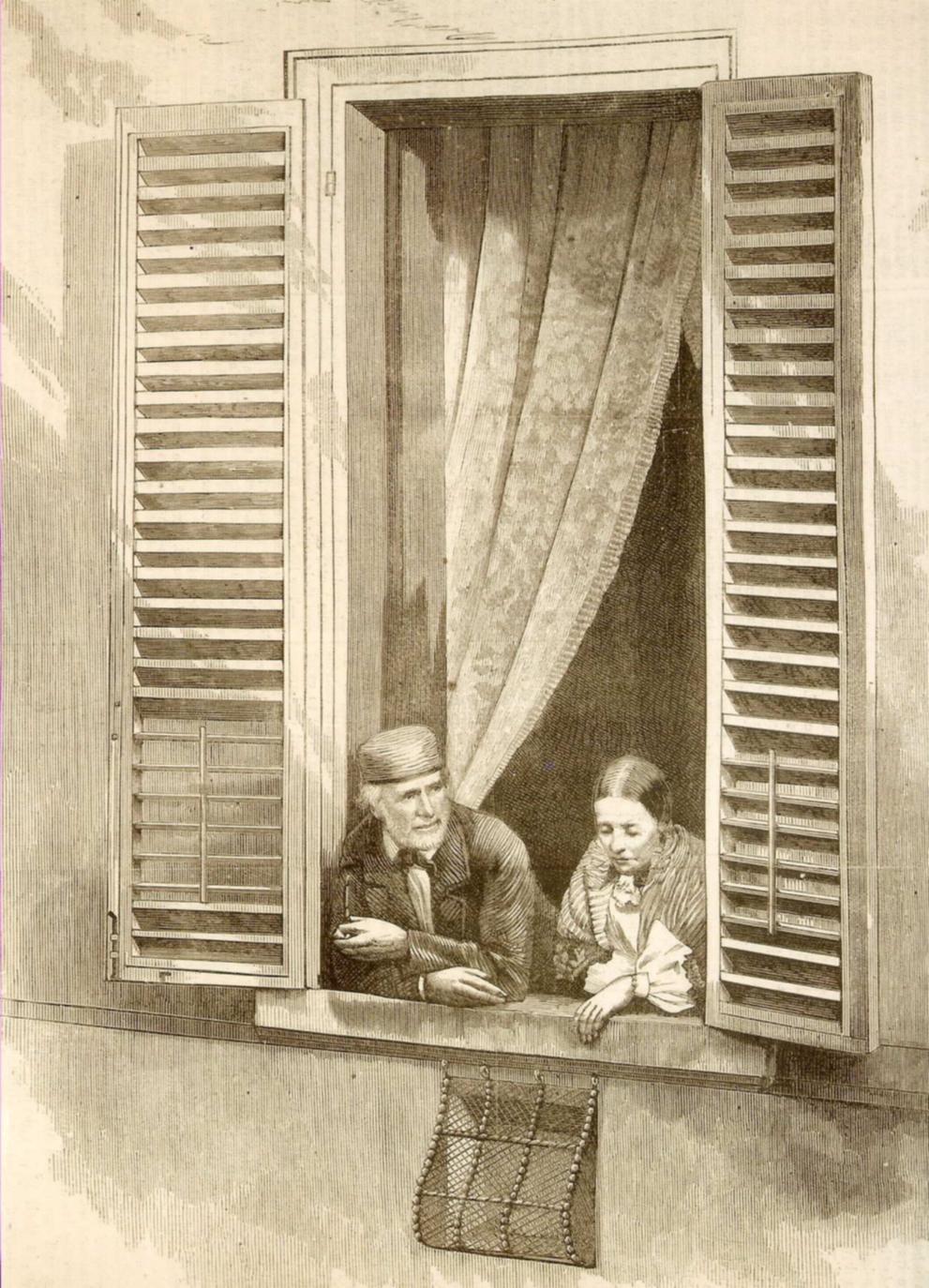

Casa Guidi (1), by George Mignaty, 1861

These

hypertexted numbers signify

places that can be found on map.

Casa Guidi

(1) is open on Monday, Wednesday and Friday from

3:00 until 6:00, except in winter. The English

Cemetery (16), is open

Monday morning, 9:00-12:00, Tuesday through Friday afternoons,

summer, 3:00-6:00 p.m., winter, 2:00-5:00 p.m.

AUDIO FILES OF

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING'S FLORENCE

♫

CASA GUIDI WINDOWS

♫

AURORA

LEIGH & POLITICAL POEMS

to accompany Elizabeth Barrett Browning's

Florence

♫

PREFACE

Elizabeth

Barrett Moulton Barrett, crippled by childhood tuberculosis and

already a successful poet, eloped at forty with Robert Browning,

her entourage including Lily Wilson, her maid, and the spaniel

Flush, coming, by way of Paris, Vaucluse and Pisa, September,

1846, reaching Florence in April 1847, then going to Vallombrosa

in July, on their returning finding Casa Guidi in

Via Maggio (1)

which became their home for the rest of their marriage,

immediately meeting Hiram Powers, the great American sculptor,

and soon after the French sculptress, Félicie de Fauveau.

Miss Mitford gives Flush to Elizabeth Barrett in Wimpole Street,

Marylbourn, London, drawings by Vanessa Bell, as endpapers to

her sister Virginia Woolf's book, Flush

Elizabeth Barrett

Browning at Casa Guidi (1)

in Florence with Flush, but which actually does not have a view

of the Duomo and its Giotto Bell Tower, only the wall of the San

Felice church.

Casa Guidi

is in the Oltrarno, the other side of the Arno river and best

reached by the Ponte Santa Trinità with its sculptures of

Spring, Summer, Autumn and shivering Winter, then up the Via

Maggio to the little square with its great column by Casa Guidi

the church of San Felice. On its other side is the the

huge and grim Pitti Palace, then Florence's political centre

as the residence first of the Grand Duke Leopold, then of King

Victor Emanuel. The plaque above the door on the left

proclaims that Elizabeth's poetry made a golden ring between

Italy and England. In Casa Guidi Windows I she

describe seeing the joyous procession up the Via Maggio from

the Ponte Santa Trinita to the Grand duke's palace, in Casa

Guidi Windows II she describes seeing the invading

Austrian army in their white uniforms with their cannons

coming up the street by Santa Felicita's church.

Elizabeth

became friends with Margaret Fuller, her presumed husband and

their child Angelo who, fleeing the disaster of Giuseppe

Mazzini's Roman Republic came to Florence in April 1850,

shortly before their deaths by drowning in the ship

'Elizabeth' off Fire Island, on 19 July of that year.

Elizabeth would turn her into the character of Aurora of her Aurora

Leigh. Another of their American friends was Harriet

Beecher Stowe, who wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin against

slavery in America, while others included the Hawthornes and

the young Kate Field, journalist for the Atlantic Monthly,

and Harriet Hosmer, sculptress, who sculpted their

'Clasped Hands' when they were staying in Rome.

Harriet Hosmer's Clasped Hands of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert

Browning

Their English friends included Walter Savage Landor, whom they would eventually care for in his senile dementia, Elizabeth speaking of him having 'the most beautiful sea-foam of a beard you ever saw, all in a curl and white bubblement of beauty'; Seymour Kirkup, who discovered Giotto's portrait of Dante in the Bargello Magdalen Chapel (7); John Ruskin, who wrote Mornings in Florence; Tennyson's brother, Frederick Tennyson; Robert Lytton, who became Viceroy of India; and - at a distance - the Trollopes. Elizabeth also kept George Eliot at a distance when that novelist came to Italy to research the period of Savonarola for Romola.

Elizabeth placed on the Casa Guidi marble mantelpiece the two engravings from Hengist Horne's New Spirit of the Age, which she helped edit in her Wimpole Street sickroom, of Lord Tennyson, Poet Laureate, and Robert Browning, author of Paracelsus. She had jokingly proposed to both of them in her 1844 poem, Lady Geraldine's Courtship, before meeting either poet, when speaking of her heroine reading with her lover hero, of aaa

aaa

And these images would be joined on the mantelpiece in Casa Guidi (1) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti's sketch of Tennyson reading 'Maud', about which event Elizabeth wrote in October 1855.

Robert,

meanwhile, furnished the vast room in which Elizabeth wrote (and

which she said was 'like a room in a novel') with antiques,

including its great gold-framed mirror, and paintings, many

pieces resulting from the suppression of monasteries, bought in

San Lorenzo Market (13)

where, one day, he found 'The Old Yellow Book' about a man's

murder of his wife.

The visit to

Vallombrosa was succeeded by stays in Bagni di Lucca where, one

morning in 1849, Elizabeth shyly gave Robert her sonnets she had

written of their love, now years ago, in her Wimpole Street

sickroom. And which he promptly published as Sonnets from

the Portuguese. It was here in Casa Guidi (1),

9 March 1849, that Pen Browning, their child, was born, about

whom Elizabeth would write in both Casa Guidi Windows II

and in Aurora Leigh. It was here that Elizabeth saw the

Grand Duke come back with the Austrian Army, 12 April 1848, to

oppress the Florentine people, forbidding their flag of red,

white and green, from Dante's Beatrice in Purgatorio.

Elizabeth defiantly furnished her salon with white and red

curtains against its green walls, those colours of the Italian

flag forbidden by the Grand Duke. She would write in the low

deckchair in the foreground of George Mignaty's painting,

stuffing the sheets between the cushions when visitors called.

It was here in the bedroom, 29 June 1861, that Elizabeth Barrett

Browning died, his father cutting off Pen's curls and also hers

and journeying back to England with the boy, after commissioning

George Mignaty to paint the room in which she had written so

many of her letters and her major poems.

Robert after her death went on to write the murder story of The Ring and the Book, from the 'Old Yellow Book' he had found in San Lorenzo Market, beginning it and ending it speaking of his wife. Their son Pen when he grew up preferred the Continent to England, became a painter and a sculptor, studying under Rodin, one bronze bust he made being of 'Pompilia', his model, his illegitimate Breton daughter, Ginevra, and thus Elizabeth's granddaughter. Robert and Elizabeth had shared a friendship with Isa Blagden, which Robert continued following his wife's death. Elizabeth had used the landscape from Isa's Bellosguardo terrace for the setting of Aurora's house in Florence - though its interior is that of via Maggio's Casa Guidi (1).

The View from Bellosguardo (17), reached by way of

the Oltrarno (beyond the Arno and beyond this map) Porta

Romana and turning right and climbing up the hill. This

painting by the Pre-Raphaelite John Brett of Bellosguardo

shows the medieval walls before Giuseppe Poggi tore them

down to make the viale, modeled on Parisian boulevards, at

the Risorgimento when Florence briefly became capital of

Italy. The Jewish Cemetery can be seen at the extreme left

outside the wall, just as the Protestant Cemetery (16) was just outside the

medieval wall but on the opposite side of Florence.

Though from a Jamaican family whose wealth came from slaves, Elizabeth hated slavery and oppression, using her poetry to write for the liberation of slaves, children, women, nations, Greece, and also Italy, in her day ground under by the Austrians, the Spanish, the French, the Pope. She witnessed the Austrian army passing beneath her Casa Guidi windows. She, as a woman, was barred from reading newspapers and novels at the Gabinetto Vieusseux, though her husband and Fedor Dosteivsky had that liberty. She joked that the periodicals are guarded there like Hesperian apples by the dragons of the place. She did not live to see the freedom of Rome with Italy. Her support of Italy's Risorgimento is acknowledged in the plaque on Casa Guidi which proclaims in Italian that she 'made of her verse a golden ring wedding Italy to England'. Leighton, who studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti (14), designed her tomb in the English Cemetery (16), 1861, with a broken slave shackle upon a garlanded harp.

One could have wished Robert Browning and Lord Leighton had seen fit to include pomegranates on Elizabeth's tomb in the Piazzale Donatello. Robert was to wed his poetry to Elizabeth's in The Ring and the Book through Castellani's lilied ring. Elizabeth had powerfully wed her poetry to Robert's through her embroidering of the High Priestly pomegranate into Lady Geraldine's Courtship, into her Letters to Robert Browning, and, later, in Aurora Leigh.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Tomb, 'English

Cemetery'

a

a

Frederic Lord Leighton, Self-Portraits, In

Youth, In Maturity, Uffizi Gallery (5)

Instead, Leighton's tomb has the thistle, rose and shamrock of the British Isles, the lily of Florence, the laurel of the poet's crown, and the three lyres of poetry, one with the broken slave shackle and roses, shown above, the two others with olive branches.

The Brownings had been accompanied on their honeymoon by Anna Jameson, a fine art historian, and John Ruskin was sketching in Pisa when they arrived there. Anna Jameson's father painted miniatures on ivory of the paintings in Windsor Castle and his red-haired daughter knew these paintings well and others and wrote about them in books. Among them would have been Johann Zoffany's painting of the Uffizi's Tribune (5) which we shall see below. The Brownings numbered among their friends the Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

a

a

Robert

Browning by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

and Holman

Hunt's wife Fanny would come to be buried beside Elizabeth in

the English

Cemetery in a tomb Hunt sculpted. The Brownings were an

important link between Italy and England's Pre-Raphaelites, also

her Anglican Oxford Movement which sought likewise to return to

the Catholicism of medieval England. The Brownings were English in Italy.

While Dante Gabriel Rossetti's father

was exiled from Italy, teaching Dante in London. His son

imagined the Florence he never saw in his early and most

self-referential painting of 'Dante painting Angels', a

scene he took from Dante Alighieri's Vita Nuova, and

which gives the Arno and its bridges (4).

Dante

Gabriel Rossetti,

Dante Painting Angels, Ashmolean Museum

A similar self-referential painting was executed by the similarly very young, but academic painter, Frederic Leighton, who had studied at Florence's Accademia di Belle Arti (14).

Elizabeth had written the note to Casa Guidi Windows, I. 334 [1848], about Cimabue's Madonna, 'A king stood bare before its sovran grace: Charles of Anjou, whom, in his passage through Florence Cimabue allowed to see this picture while yet in his "Bottega". The populace followed the royal visitor, and, in the universal delight and admiration, the quarter of the city in which the artist lived was called "Borgo Allegri". The picture was carried in triumph to the church, and deposited there. E.B.B.' In Elizabeth Barrett Browning's day the Cimabue painting was still in Santa Maria Novella (11). Thus she tells the story that will become the painting. Then she wrote joyously in a 13 May 1855 letter about Queen Victoria purchasing the not yet twenty-five-year-old Frederic Leighton's 'Carrying Cimabue's Madonna through the Borgo Allegri' (8). (If one looks with care to the top of the scene on the right, one can see San Miniato. (3)) In July-August of that year Robert Browning introduced Frederic Leighton to John Ruskin.

Elizabeth

filled her letters and poems with Florence, giving as it were, a

guidebook to Florentine art. One finds her in the letters

speaking of the 'golden Arno', at sunset, a 'silver arrow'

cleaving the palaces (4),

of strolling with Robert on moonlit evenings to the Loggia to

look at the 'Perseus' (6).

Recently, Florentine churches have been scrubbed clean. In Elizabeth's day they were lit with candles which darkened the walls but made the gold leaf gleam. Our selection of images are partly taken from an English water colourist, Colonel C. Goff, because these evoke what Elizabeth herself saw. Then I had no sooner started drafting together this book than in walked a tall young Yorkshire artist, James Rotherham, with portfolio, - including a drawing of Cellini's 'Perseus' in the Loggia dei Lanzi (6). I had met him at Mass morning after morning at the Santissima Annunziata (15) in Florence. Together we plotted how best to illustrate Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poetry about Florence and his art. His second contribution - the Santissima Annunziata's 'Madonna of the Seven Sorrows'. All this editorializing transpired in the English Cemetery in Piazzale Donatello (17), where Elizabeth Barrett Browning is buried and beside which is Michele Gordigiani's studio.

Elizabeth besides filled her letters with Italian politics, European politics, filtered through her passionate love of liberty, functioning to her large circle of friends as a journalist, much as had also Jessie White Mario and Margaret Fuller and Kate Field. Though she lamented being forbidden to enter, as a woman, the Gabinetto Vieusseux (sacred to men such as Robert Browning, John Ruskin and Fedor Dostoevsky), and thus was denied access to newspapers, censored during that period by the Grand Duke. Her letters and her poetry witness the birth, the freeing, of a nation, whose capital for a brief while came to be her Florence.

In the pages that follow Elizabeth uses the Italian forms of terza rima for Casa Guidi Windows, and the sonnet, for 'Hiram Powers' Greek Slave', and the Sonnets from the Portuguese, English blank verse for Aurora Leigh, the ballad form for 'An August Voice', as well as 'The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim's Point', and the classical Pindaric Ode for her eulogy on Camille Cavour, recalling that Corinna won the garland for that form in ancient Greece. This book is anthology and guide, an anthology of Elizabeth Barrett Browning's verse, a historical guide for us now to her beloved city of Florence, the 'golden ring between Italy and England'.

Lord Leighton's Florentine Lily

on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Tomb

HER POETRY ABOUT FLORENCE I

[Hypertexted numbers signify places that can

be found on map. Call up both

files and cycle between them. Casa Guidi (1) is open on Monday,

Wednesday and Friday from 3:00 until 6:00, except in winter. The

English

Cemetery (16), is open

Monday morning, 9:00-12:00, Tuesday through Friday afternoons,

summer, 3:00-6:00 p.m., winter, 2:00-5:00 p.m.]

AUDIO FILE OF

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING'S FLORENCE, ♫

CASA GUIDI WINDOWS, to

accompany Elizabeth

Barrett Browning's Florence and Map of Florence.

CASA GUIDI WINDOWS I [1848]

I

I heard last night a little

child go singing

‘Neath Casa Guidi

windows (1), by the church,

‘O bella libertà, O

bella!’ stringing

The same words still on

notes he went in search

So high for, you concluded the upspringing

Of such a nimble bird to

sky from perch

Must leave the whole bush in a tremble green;

And that the heart of

Italy must beat,

While such a voice had leave to rise serene

‘Twixt church and palace

of a Florence street!

A little child, too, who not long had been

By mother’s finger

steadied on his feet;

And still O bella libertà he sang.

Pen Browning, Elizabeth's son,

born in Florence, 9 March 1849

It was he who arranged for the above plaque to be placed on

Casa guidi

. . .

I can but muse in hope upon this shore

Of golden Arno as it shoots away

Straight through the heart of Florence, ‘neath

the four

Bent

bridges (4), seeming to strain off like bows,

And tremble, while the

arrowy undertide

Shoots on and cleaves the marble as

it goes,

And strikes up palace-walls on either side,

And froths the cornice out in

glittering rows,

. . .

How beautiful! The mountains from without

In silence listen for the word said

next,

(What word will men say?) here

where Giotto planted

His campanile (10), like an unperplexed

Question to Heaven, concerning the

things granted

To a great people.

Colonel Goff, Water Colour, Prior to 1905

What word says God? The sculptor’s Night and Day

And Dawn and Twilight, wait in

marble scorn,

. . .

Michelangelo, Aurora, Medici Tombs, San Lorenzo

In Florence and the great world outside his

Florence,

That’s Michel Angelo! His

statues wait

In the small chapel of the dim St

Lawrence! (12)

Day’s eyes are breaking bold

and passionate

Over his shoulder, and will flash

aborrence

On darkness, and with level

looks meet fate,

When once loose from that marble film

of theirs:

The Night has wild dreams in her sleep, the Dawn

Is haggard as the sleepless: Twilight

wears

A sort of horror: as the veil withdrawn

‘Twixt the artist’s soul and works

had left them heirs

Of the deep thoughts which would not quail nor

fawn,

Of angers and contempts, of hope and

love;

For not without a meaning did he place

The princely Urbino on the seat above

With everlasting shadow on his face;

While the slow dawns and twilights

disapprove

The aches of his long-exhausted race,

Which never more shall clog the feet

of men.

X

Or enter, in your Florence

wanderings,

The church of St. Maria

Novella (11).

You pass

The left stair, where, at plague-time. Machiavel

Saw one with set fair face as

in a glass,

Dressed out against the fear of death and hell,

Rustling her silks in pauses of the

mass,

To keep the thought off how her husband fell,

When she left home, stark dead across

her feet, -

The stair leads up to what Orgagna gave

Of Dante's daemons; but you, passing

it,

Ascend the right stair from the farther nave,

To muse in a small chapel scarcely

lit

By Cimabue's Virgin.

Colonel Goff, Water Colour, Santa Maria

Novella Madonna and Child, Cimabue, actually the Rucellai

Madonna

Bright and brave,

That picture was accounted, mark of

old:

A king stood bare before its

sovran grace,

A reverent people shouted to behold

The picture, not the king, and even the place

Containing such a miracle grew bold,

Named the

Glad Borgo (8) from that beauteous

face . . . .

. . .

Perseus, Loggia, Benvenuto Cellini, drawn by James

Rotherham (6)

No the

people sought no wings

From Perseus in the Loggia,

nor implored

An inspiration in the place beside,

From that

dim bust of Brutus (7), jagged and grand,

Where Buonarotti

passionately tried

Out of the clenched marble to demand

The head of Rome’s sublimest homicide,

Then dropt the quivering mallet from

his hand,

Despairing he could find no model stuff

Of Brutus, in all Florence . . .

Michelangelo,

Bust of Brutus, Bargello Museum (7)

XXVIII

. . .

England claims, by trump of poetry,

Verona, Venice, the Ravenna-shore

And dearer holds her Milton’s Fiesole

Than Langland’s Malvern with the

stars in flower

. . .

XXIX

And Vallombrosa (18), we two went to see

Last June, beloved companion, - where

sublime

The mountains live in holy families,

And the slow pinewoods ever climb and

climb

Half way up their breasts, just stagger as they

seize

Some grey crag - drop back with it

many a time,

And straggle blindly down the precipice!

The Vallombrosan brooks were strewn

as thick

That June-day, knee-deep, with dead beechen

leaves,

As Milton saw them ere his heart grew sick,

And his eyes blind. . . .

O waterfalls

And forests! Sound and

silence! Mountains bare,

That leap up peak by peak, and catch

the palls

Of purple and silver mist to rend and share

With one another, at electric calls

Of life in the sunbeams, - til we cannot dare

Fix your shapes, learn your number!

We must think

Your beauty and your glory helped to fill

The cup of Milton’s soul so to the

brink,

That he no more was thirsty when God’s will

Had shattered to his sense the last

chain-link

By which he had drawn from Nature’s visible

The fresh well-water. Satisfied by

this,

He sang of Adam’s paradise and smiled,

Remembering Vallombrosa. Therefore is

The place divine to English man and child –

We all love Italy.

XXX

. . .

. . .

CASA GUIDI WINDOWS II [1851]

XXV

The sun strikes, through the

windows, up the floor (1)

Stand out in it, my own young Florentine,

Not two years old, and let me see

thee more!

It grows along thy amber curls, to shine

Brighter than elsewhere. Now, look

straight before,

And fix thy brave blue English eyes on mine,

And from thy soul, which fronts the

future so,

With unabashed and unabated gaze,

Teach me to hope for, what the Angels

know

When they smile clear as thou dost.

Pen Browning

XXX

‘Here’s sculpture! Ah, we live too! Why not

throw

Our life into our marbles? Art

has place

For other artists after Angelo.’ (7,12,14)

HIRAM POWERS’ GREEK SLAVE [1850]

Elizabeth saw this statue in Hiram Powers' studio in Florence, prior to its presence in the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition, and wrote this powerful sonnet to it against Slavery.

They say Ideal Beauty cannot enter

The house of anguish. On the

threshold stands

An alien Image with the shackled hands,

Called the Greek Slave: as if the sculptor meant

her,

(That passionless perfection which he lent her,

Shadowed, not darkened, where the sill expands)

To, so, confront men’s crimes in different

lands,

With man’s ideal sense. Pierce to the centre,

Art’s fiery finger! - and break up erelong

The serfdom of this world! Appeal, fair

stone,

From God’s pure heights of beauty, against man’s

wrong!

Catch up in thy divine face, not alone

East griefs but west, - and strike and shame the

strong,

By thunders of white silence, overthrown!

Longworth Powers' Photograph of Hiram Powers. EBB

spoke of Powers' expressive black eyes.

He is buried near Elizabeth Barrett Browning

in Florence's English

Cemetery (16)

♫ ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING'S FLORENCE

HER POETRY ABOUT FLORENCE

II

a

AURORA LEIGH I [1856]

The Piazza of the Santissima Annunziata

A train of priestly banners, cross and psalm, -

The white-veiled rose-crowned

maidens holding up

Tall tapers, weighty for such wrists, aslant

To the blue luminous tremor of the air,

And letting drop the white wax as they went

To eat the bishop’s wafer in the church;

Colonel Goff, First Communion, Fiesole

. . . There’s a verse he set

In Santa Croce (8) to her memory,

‘Weep for an infant too young

to weep much

when death removed this mother’ - stops the

mirth

To-day on women’s faces when they walk

With rosy children hanging on their gowns,

Under the cloister, to escape the sun

That scorches in the piazza.

Colonel Goff, Santa Croce (8)

The child Aurora gazes on the painting of her dead mother:

Madonna of the Seven Sorrows, Santissima Annunziata, Water Colour, James Rotherham (15)

or,

Lamia

in

her first

Moonlighted pallor, ere she shrunk and blinked,

And,

shuddering, wriggled down to the unclean;

Or, my

own mother, leaving her last smile

In her

last kiss, upon the baby-mouth

My

father pushed down on the bed for that, -

Or my

dead mother, without smile or kiss,

Buried at Florence

(8,16).

VI

Marian and Aurora gaze on the sleeping child, who is both Elizabeth's Penini and Margaret Fuller's Angelo:

B.png)

Sandro

Botticelli, Madonna della Melagrana, Detail of Child with

Pomegranate

VII

I found a house, at Florence,

on the hill

Of Bellosguardo (17).

‘Tis a tower that keeps

A post of double observation o’er

The valley of Arno (holding as a hand

The outspread city (4))

straight toward Fiesole

And Mount Morello and the setting sun, -

The Vallombrosan mountains to the right,

Which sunrise fills as full as crystal cups

Wine-filled, and red to the brim because it’s

red.

No sun could die, not yet be born, unseen

By dwellers at my villa: morn and eve

Were magnified before us in the pure

Illimitable space and pause of sky,

Intense as angels’ garments blanched with God,

Less blue than radiant. From the outer wall

Of the garden, dropped the mystic floating grey

Of olive-trees, (with interruptions green

From maize and vine) until ‘twas caught and torn

On that abrupt black line of cypresses

Which signed the way to Florence. Beautiful

The city lay along the ample vale,

Cathedral, tower and palace, piazza and street;

The river trailing like a silver cord

Through all, and curling loosely, both before

And after, over the whole stretch of land

Sown whitely up and down its opposite slopes

With farms and villas.

Engraving of Bellosguardo

The noon was hot; the air scorched like the sun,

And was shut out. The closed persiani threw

Their long-scored shadows on my villa-floor,

And interlined the golden atmosphere

Straight, still, - across the pictures on the

wall,

The statuette on the console, (of young Love

And Psyche made one marble by a kiss) (5)

The low couch were I leaned, the table near,

The vase of lilies, Marian pulled last night

. . .

aaa

aaa

Canova, Cupid and Psyche,

Louvre

Amore and Psyche, Uffizi (5)

. . .

Here Elizabeth describes Casa Guidi rather than Bellosguardo, and, with the statue imagined as on the console, she remembers her translation of Apuleius, Metamorphoses IV. Giorgio Mignaty's painting of Casa Guidi for Robert Browning at EBB's death. (1)

She has appropriated the statue of Cupid and Psyche from the Uffizi, seen here to the left in Johann Zoffany, 'The Tribune of the Uffizi', 1772-78. (5)

And only once, at the Santissima (15),

I

almost chanced upon a man I knew.

He

saw

me

certainly.

I

slipped so quick behind the porphyry plinth,

And

left him dubious if 'twas really I.

Engraving of Miracle of Blind Girl Recovering

her Sight at Santissima Annunziata

VIII

Gradually

The purple and transparent

shadows slow

Had filled up the whole valley to the brim,

And flooded all the city, which you saw

As some drowned city in some enchanted sea . . .

The duomo bell (9,10)

Strikes ten, as if it struck ten fathoms down,

So

deep; and fifty churches answer it

The same, with fifty various instances.

Some gaslights tremble along squares and

streets;

The Pitti’s

palace-front is drawn in fire (2);

And, past the quays,

Maria Novella’s Place (11),

In which the mystic obelisks

stand up

Triangular, pyramidal, each

based

On a single trine of brazen tortoises,

To guard that fair church, Buonarotti’s Bride,

That stares out from her large blind dial-eyes,

Her quadrant and armillary dials, black

With rhythms of many suns and moons

. . .

Colonel Goff, Santa Maria Novella

IX

Elizabeth ends Aurora Leigh imagining the then twelve-gated Florence as the heavenly Jerusalem, from the Book of Revelation, while Aurora and Romney (who is now blind), gaze down upon it from Bellosguardo (17)

. . . .Upon the thought of perfect noon. - 'Jasper first,' I said,

AN AUGUST VOICE

You'll take back your Grand-duke?

I made the treaty upon it.

Just venture a quiet rebuke;

Dall'Ongaro write him a sonnet;

Ricasoli gently explain

Some need of the constitution:

He'll swear to it over again,

Providing an "easy solution."

You'll call back the Grand-duke.

. . . .

He is not pure altogether.

For instance, the oath which he took

(In the Forty-eight rough weather)

He'd "nail your flag to his mast,"

Then softly scuttled the boat you

Hoped to escape in at last

. . . .

You'll take back your Grand-duke?

There are some things to object to,

He cheated, betrayed, and

forsook,

Then called in the foe to protect

you.

He taxed you for wines and for meats

Throughout that eight years' pastime

Of Austria's drum in your streets -

Of course you remember the last time

You called back your Grand-duke?

. . . .

His love of kin you discern

By his hate of your flag and me -

So decidedly apt to turn

All colours at the sight of the

Three.

You'll call back the Grand-duke.

You'll take back your Grand-duke?

'Twas weak that he fled from the Pitti

(2);

But consider how little he

shook

At thought of bombarding your city!

. . . .

You'll call back the Grand-duke.

From LAST POEMS [1862]

KING VICTOR EMANUEL ENTERING FLORENCE, APRIL, 1860

King of us all, we cried to thee, cried to thee,

Trampled to earth by the

beasts impure,

Dragged by the chariots

which shame as they roll:

The dust of our torment far

and wide to thee

Went up, dark'ning thy royal soul.

Be witness,

Cavour,

That the King was sad for the people in thrall,

This King of

us all!

a

a

Camille, Count Cavour, by

Michele Gordigiani who also painted the portraits

of Robert and Elizabeth in his studio by the English

Cemetery (16)

. . . .

This is our beautiful

Italy's birthday;

High-thoughted souls,

whether many or fewer,

Bring her the gift, and

wish her the good,

While Heaven presents on this

sunny earth-day

The noble King to the

land renewed:

Be witness, Cavour!

Roar, cannon-mouths! Proclaim, install

The

King

of

us all!

Grave he rides through the Florence gateway,

Clenching his face

into calm, to immure

His struggling heart

till it half disappears;

If he relaxed for a moment,

straightway

He would break out

into passionate tears -

(Be witness, Cavour!)

While rings the cry without interval,

"Live,

King

of

us all!"

. . . .

Flowers, flowers, from the flowery city!

Such innocent thanks for a

deed so pure,

As, melting away for joy

into flowers,

The nation invites him to enter his

Pitti (2)

And evermore reign in

this Florence of ours.

Be witness, Cavour!

He'll stand where the reptiles were used to

crawl,

This King of us all.

. . . .

[Hpertexted numbers signify places that can be found on map. Casa Guidi (1) is open on Monday, Wednesday and Friday from 3:00 until 6:00, except in winter. The English Cemetery (16), is open Monday morning, 9:00-12:00, Tuesday through Friday afternoons, summer, 3:00-6:00 p.m., winter, 2:00-5:00 p.m.]

Elizabeth Barrett Browning twice describes the

silver arrow of the Arno River (4)

shooting through the city of Florence. In Casa Guidi

Windows I.52-59

I can but muse in hope upon

this shore

Of

golden

Arno

as it shoots away

Straight through the heart of Florence, 'neath the four

Bent

bridges

(4), seeming to strain

off like bows,

And

tremble, while the arrowy undertide

Shoots

on

and

cleaves the marble as it goes,

And

strikes up palace-walls on either side,

And

froths

the

cornice out in glittering rows,

With

doors and windows quaintly multiplied,

And

terrace-sweeps,

and

gazers upon all,

By

whom if flower or kerchief were thrown out

From

any

lattice

there, the same would fall

Into

the river underneath no doubt,

It

runs

so

close and fast, 'twixt wall and wall.

How

beautiful.

And in Aurora Leigh VII.534-537:

Beautiful

The city lay along the ample

vale,

Cathedral, tower and

palace, piazza and street,

The river trailing like a

silver cord

Through all (4), and curling loosely,

both before

And after, over the whole

stretch of land

Sown whitely up and down

its opposite slopes

With farms and

villas.

Robert Browning, The Ring and

the Book

Virginia Woolf, Flush:

A Biography

Flush:

Una biografia. in italiano

Before the Risorgimento, Florence's walls and city gates, built first by Arnolfo di Cambio, then by Michelangelo, had enclosed her. This map shows Florence as it was in the earlier nineteenth century, from Augustus Hare's Florence:

Protestant Cemetery

Before 1877

IN STOCK

IN STOCKIN STOCK

Oh Bella Libertà! Le Poesie di Elizabeth Barrett Browning. A cura di Rita Severi e Julia Bolton Holloway. Firenze: Le Lettere, 2022. 290 pp.

For other Florence guides/Per altre guide di Firenze: https://www.florin.ms/GoldenRingGuides.html

To donate to the restoration by Roma of Florence's formerly abandoned English Cemetery and to its Library click on our Aureo Anello Associazione's PayPal button:

THANKYOU!