SOPHIA PEABODY HAWTHORNE

FLORENCE

EXTRACTS FROM 'NOTES IN ITALY' II

July 2nd. - The Brownings went to France yesterday morning, and there seems to be nobody in Florence now for us.

We have been to the Duomo to-day 1. It was in nice order, and the ugly chairs removed, and we could see the beauty of the pavement, as not before. We walked all round the chapels, and upon one, dedicated to the Virgin, was an image of her, with a necklace of large diamonds; and she stands upon a crescent moon, five or six inches in its curve, made entirely of diamonds. As the altar was blazing with lighted candles, the effect was dazzling.

I had a better view of Michel Angelo's Pietà [now removed to the Opera del Duomo across the street], and the face and head of Christ are beautiful. Mary is older than she is represented in the Pietà at St Peter's, but very grand - as is the whole group. John and Mary Magdalen help support the body of Jesus. It is lamentable that such a work should be in so dark a place, where it is nearly impossible ever to see it all, except the outline. The windows were superb to-day on the eastern side, with the sun shining through. The Cathedral is impressive and noble, but very small in comparison to St Peters, and it somehow reveals the immensity of St Peter's, which never was large enough to meet my expectations, when I was in it. It is strange that the Flroentines do not fill the Duomo with superior works of art; but it is far better to have none than the pictures and statues of medium erit that usually are found in churches.

Afterward we long contemplated the Gates of Gates of the Baptistery, and then endeavored to find the via Faenza 33, and the building in which is the Cenacolo of Raphael [now attributed to Perugino]. After some straying, we found it, and then Mr Hawthorne left; for he said he could not look at a fresco to-day. A deplorable old beggar rang the bell for me, for the sake of a crazia, and a civil, respectable man opened the door, and ushered me into a room, one end of which is filled with the picture I wished to see. It has evidently been cleaned, and that dangerous process would take away the delicate finish and tings and atmosphere of a work of Raphael; but it is a grand, impressive, affecting design. John's head is exceedingly beautiful. He is represented asleep or faint, as he often is at the supper - I do not know why, unless it were impossible to portray his grief and amazement at the words, 'one of you shall betray me'. There is lovely repose in the perfect features and attitude. His head rests on his arm before Christ, who, with upraised hand, looks directly and deprecatingly, but with gentle majesty, at Judas, who is alone on this side the table, and stares out of the picture, with an uneasy and sinister glance, grasping the bag in his left hand. St James is, like John, very young and beautiful, with a clear, open brow, and an expression of calm suprise, as if he could not readily conceive of such a crime. The older apostles are noble, some of them with a most tender sorrow, and all astonished, holding their knives and bread and cups suspended at the fearful words. Thaddeus is also represented as youthful. I was quite alone in the building. Not a sound broke the profound silence.

The arched, vaulted room was the Refectory of the Convent of San Onofrio, now repaired. Antique red-cusioned chairs were ranged round three sides; and beneath the picture, on the fourth side, was a carved settle. Sitting there so still, I seemed to be present at the very moment when Jesus pronounced the sentence that struck such amazement and dismay into the hearts of his disciples, and they all became living persons to me. The fresco was very splendid in color once, with a great deal of gold. The dishes on the table are of elegant form, like Greek paterae; but the whole effect is simple and centres upon Christ and Judas. Just as Perugino's Pietà in the Academy made me more truly feel than ever before that Christ was curcified for man, so this assured me of that most affecting last supper on earth of Jesus and his friends. So powerful is the purpose and sentiment of the great masters, that we become possessed of the same. I often go round the chapels of the churches, and look at the altar-pictures, and see and feel nothing, as they usually are. But suddenly I am arrested, and always by the devout, religious, and inspired painters of the olden time, of whom Raphael was the consummate flower.

Above, and far beyond the group at table, through arches, we see a landscape, with the trees and rocks and hills that drive Ruskin mad; but I think they are always in keeping with the figures in Raphaelite and pre-Raphaelite pictures, and I like them. They give distance and scope, without overwhelming the main design, and therefore have an artistic propriety.

The Egyptian Museum is in the same building [now moved to the Palazzo della Crocetta, Via della Colonna], and I wished to see a war-chariot that was there. There were mummies, in and out of mummy-cases, innumerable carved objects in precious stones, frogs as big only as a pea, and large and small scaribaei of various substances - gods, altars, shrines, bas-reliefs, stele drawings on stucco, and one curious portrait of a handsome, unamiable lady, with hair dressed in the fashion of to-day. It has taken three or more thousand years for this style to come round again. In what a large orbit moves Fashion!

The war chariot is made of wood - a very light kind of wood, with as little framework and weight as possible, The seat (or stand, rather) is woven of reeds and straw. It must have flown like the wind, with fleet horses. Two very large, airy wheels were on each side; and it was a Scythian chariot, after all, and I believe I expected to see an Egyptian one. But if the chariots of éharoah were like this, they certainly could not withstand the waves. Why should our carriages be so ponderous? It is, at least, a pity to load our horses with such unnecessary weight. Remote antiquity might teach us a great deal, though we brag so perpetually of our improvements. I laid my hand upon the woven stand, wondering whose brave feet had held their place upon it in the thick of battle, three, or perhaps four, thousand years ago. Just now I had been in the Holy Land, and now I was in Egypt; for in Egypt this chariot was found.

When I was about leaving the building, I offered the custode a fee, but, with a polite bow, he protested that I was 'senza obligazione', and I was really obliged to put my silver back into my purse, with speechless surprise. It is the first time in Europe that I have known a custode to refuse the money dropping into his hand, though attendants do not always demand it.

On my way home I stopped at the Baptistery 3, and looked at Ghiberti's other door, which is also beautiful, and represents the Life of Christ. There is perfect grace, and delicate, forcible expression in the faces and forms; and I think it would be considered a masterpiece, if the eastern gate were not so peerless. The third one is the Life of St John the Baptist, by Pisano. Inside, I looked at a wooden statue of Mary Magdalen [now removed to the Opera del Duomo 1], meagre, forlorn, and sad, with abundant hair enveloping her nude and wasted girue. I had come in, because, while gazing at Pisano's door, I felt a great drop of water fall on my nose, and instantly down poured a flood, and the thunder rolled; so I fled into the sanctuary, and sat down. I could have stayed there contentedly for a long time, but I had not my watch, and was afraid I should be too late for dinner; so I summoned a carriage and drove home. For more than two hours it continued to rain, thunder and lighten; then it cleared lustrously, and R and I walked out of the Porta Romana up the spacious avenue of the Grand Duke's villa, about a mile long, close by the city. It is a broad carriage-road, with nice foot-walks beneath the shade-trees on each side, open and free to all, in true Tuscan princely style. * * *

At the gate of the Villa were two

marble statues - one, Jupiter hurling thunderbolts with the

utmost furor,

- a strange figure to place at the entrance of the ducal

residence, though

significant and appropriate, considering how the Florentine

rulers behave.

The other is Atlas, I suppose, with the heavens on his

shoulders. A lovely

lawn is within, surrounded with rose-trees still in bloom,

though it be

now late for roses: and beyond stretches out the palace, -

marble statues

standing in niches in front. Even into this strangers are

admitted; but

it was too late then for us. The view is extensive and rich

from the end

of the avenue, which gently, yet constantly, ascends all the

way from the

first gate.

* * * * *

Santa Maria Novella 17

July 3rd. - This morning we set forth for Santa Maria Novella, Michel Angelo's Bride. It was the church where Boccaccio's ladies met at the time of the plague, and agreed to go away together. I wished particularly to see the famous Madonna of Cimabue [now removed to the Uffizi 10], which was so superior to previous paintings of her, that it was borne through the streets in triumphal procession, before being deposited in its present chapel. The façade of this church, one of the few that is finished, is encrusted with black and white marbles in mosaic. On the right extends an arcade, and in each arch is a tomb, with the escutcheon of the person buried sulptured or modelled in stucco above. At right angles, on the left, is still another arcade, and on this side we entered a cloister - the green cloister, so called because the frescoes which cover the walls are green and brown in tint - a sort of chiar'oscuro. They are curious pictures of events in the Old Testament by Uccello and Dello, with a good deal of force and the utmost naiveté. Beneath these designs are innumerable sepulchral tablets. We walked along till we came to an open door, which we entered, and found services going on in a larrge, lofty room, covered with frescoes by Taddeo Gaddi and Simone Memmi. It was the Chapter-house. On the east side is the triumph of St Thomas Aquinas. He sits in the centre, holding an open book, which he turns to the beholders to read. At his feet crouch three promoters of heresy. On each hand, in a regular line, sit saints, apostles, virtues, and angels. In two even rows beneath are fourteen figures - popes, philosophers, saints, orators, and personified abstractions, in rows; many beautiful noble faces and forms. This was by Gaddi, and all the others are be Memmi, Opposite St Thomas is a vast composition called the Church Militant and Triumphant, containing a great mahy portraits - of Cimabue, di Lapo, Petrarch and Laura, and Boccaccio, as well as Popes and Kings. On the north side is the Crucifixion, Christ bearing the Cross, and his Descent into Hell. The famous Walter de Brienne is the Roman centurion. Opposite are scenes from St Dominic's life, as this is a Dominican church, with a convent attached. There are windows, beautiful mullioned windows, and a great door, which would effectually light the frescoes, but they were provokingly covered with dark curtains, so that it was difficult to see them well. Glorious with colour and form must have been those walls in their first ages; for they are now more than five hundred years old. The groined roof meets in a point above, with four separate subjects in each compartment. From the Chapter-house we returned to the Green Cloisters, and were going down a corridor that seemed full of paintings and tombs and sculptures, when a custode accosted us, and asked if we wished to see the Church. We followed him with his key and he led us directly to the sacristy, a lofty, Gothic apartment, with the groinings of the roof richly ornamentd; a superb window of stained glass, and mahogany presses all round, as well as one in the centre of the room. An artists was painting, and the custode introduced us to the originals of his copies. They were reliquaries by Fra Angelico, little Gothic frames, with pictures in the centres, at the foot and tops and sides; and between the central pictures and the outside were shut recesses, containing the labelled relics. I saw small bones, hair, and undistinguishable bit, but I do not know their histories. Here I found the Madonna of the Star [now in San Marco], a celebrated work of Fra Angelico - Mary, standing, in a blue robe, holding the infant, with a star blazing on her brow. All the faces were finished like minatures, and the drapery was brillian with primal colors, making carcanets of jewels, as Fra Angelico always does; and his ruby and sapphire robes and opaline faces were set on a gold background.

After carefully examining these wonderful gems, we went into glory, but with a sumptuous window of painted glass - a rose-window over the principal entrance, and a triple mullioned one over the choir. A short flight of stairs leads into the Strozzi Chapel, covered all over with frescoes, by Orgagna. One one side is Heaven, and on the other is Hell. The last had been injured and mended; but Heaven is still glorious. The Almighty is enthroned hightest, Jesus and the Virgin Mary are in the next rank, just beneath two beautiful angels; and around and below countless throngs of the ascended Just, their faces glowing and beaming with happiness and peace - thousands upon thousands. What a work for one head and one hand! but what enjoyment Orgagna must have experience in lifting up those myriad holy brows and ecstatic eyes to the smile of the Eternal Father, and the welcome of Christ and the Virgin!

Opposite is the Prince of Evil - no princely state has he, however; but he is a hideous monster, up to his middle in a caldron, in which the damned are boiling, and he eating them, as they are cooked to his taste. This is the central group. Around are separate punishments for each sin, which would not be pleasant to describe. Behind the altar is the Last Judgment, surmounted by a painted window. In the Judgment the artist has amused himself with putting many lordly personages who did not please him, among the cursed; and, out of a sepulchre, a grinning fiend is pulling a poor soul, to torment it in unseemly haste, not even waiting for it to come forth. Doubtless this soul is a portrait; for painters, as well as poets, put their enemies, or those whom they believed wicked, into the Inferno without scruple. On the other side is also a sepulchre, and from that a lovely angel is gently assisting one of the 'Blessed of my Father' to ascend. Wonderful is the contract between these opposing groups.

The choir is the work of Ghirlandaio (Domenico). One side is the Life of St John the Baptist, and the other the Life of the Virgin, in a great many compartments. Various portraits are introduced - in one group are several of the de' Medici - in another, artists, and among them Ghirlandaio himself. There is the portrait also of a great beauty of that time, Ginevra de Benci. These frescoes are very splendid. What prodigies of genius were the masters of those daus - what patience, invention, and industry! The group of women round the new-born Virgin is graceful and lovely, and one is robed in cloth of gold. All the dresses are magnificent with gold and color, and I perceive how splendid must have been this choir, with the grace and state and dignity of the figures - the true faces and the living movement - lighted with prismatic hues from the large triple Gothic window of painted glass - before the gold was dimmed or the tints faded; since, even now, it is so much more than I can apprehend at one seeing. Above, in four pointed arches of the vault, sit four Evangelists, presiding over their pictured gospels, - grand old men, prefiguring Michel Angelo's prophets; for Ghirlandaio was his master. I have not seen in anything of Ghirlandaio, however, the tremendous muscular developments which Michel Angelo delighted to render. That was 'his own music' and I cannot like it overmuch, because I do not understand anatomy, and prefer the human form rounded with 'softer solids'.

In the Gaddi Chapel, on the left, is the storied Crucifix of Brunelleschi, which he carved in wood, after seeing Donatello's, in Santa Croce. Brunelleschi told Donatello that he had cut a peasant and not a Christ, and when he had finished his own, Donatello was so astonished that he exclaimed with generous admiration, 'To thee it is granted to make the Christs, and to me the peasants'. I could not see the face distinctly enough on account of the dim shade of the chapel; but all I could see of the figure was fine; and, at any rate, the magnanimity of Donatello has consecrated it. At last we visited the Rucellai Chapel, where the celebrated Cimabue Madonna is placed [now in the Uffizi]. It has the colossal face which Cimabue and his compeers so often drew, on a rather less colossal figure, while the infant and the angels are of the natural size. But the Virgin's face is very much softer and more beautiful than any other of Cimabue, without the hard outlines of that age - a noble, sweet, and tender countenance, slightly bent on a throat disproportionately slender - with a hood almost covering the forehead. The fingers of the hands are endless and inflexible; but the baby they hold is one of the princely, divine infants, full of grace and majesty, and the six angels around, in their gold settings, are heavenly jewels of rarest beauty. In its first freshness of dazzling gold and color, it must have cast an added glory upon the day as it passed through the streets of Florence - the Holy Child blessing all men with His uplifted little hand, and the Madonna winning the worship of the thronging crowds by her queenly state and benignity of aspect. The angels are absorbed in the beatific vision of the Mother and Son. This picture is hung between two narrow windows in an unaccountable stupid manner; for the light, glaring into the eyes, prevents one from seeing well any part of it. It is disloyal to Cimabue to hang his picture so, besides being exasperating to any true lover of art. I begin thoroughly to approve the custom of Princes and Popes, of which I have heretofore complained . of taking masterpieces from churches and placing them in galleries; for in churches they are often lost, and in galleries they are found. As Mr Allston once so wisely said, 'What is the use of a picture if we cannot see it?'

The Martyrdom of St Catherine covers the right-hand wall. I looked at it with great interest, because some figures in it are said to be by Michel Angelo. St Catherine stands, raising her hands to a descending angel, who seems to bring down the retribution of heaven; for the executioners are falling about in terror or faintness, and in these writhing form I recognized Michel Angelo.

Another chapel is painted by Filippo Lippi, with traditional miracles on the sides, and the evangelists on the ceiling. St Philip is driving away a horrible dragon from the Temple of Mars on one side; on the other, Drusiana is rising from the dead. These frescoes were black and dismal, and had not the free grandeur of the Orgagnas and Ghirlandaios; but yet they were very expressive.

Over the door, leading to the campanile, is a Coronation of the Virgin, with glorified saints, by Buffalmacco, each head set in its solid golden plate - such sincerity and good faith in every line and shadow that the attract and effect are irresistable. Sometimes I feel as if academies and rules of proportion were nuisances, because they so often take the place of all that is truly valuable in a picture. It is like leaving the color out of the rose, and the perfume out of the violet - and, indeed, the soul out of the body. The inspiration of the old masters was from within, a sacred, revered flame; and with it they painted love and prayer and praise and sorrow with inevitable power, however strange and hard their lines and shapes; and finally grace and beauty of form were added thereunto more and more, till Raphael, with his radiant finger, put the seal on all endeavor. Was anything more possible? Can any one transcend him?

The Gothic nave is lofty and spacious, and along the aisles are small chapels in arches, once filled with frescoes, but now mostly in ruin. A marble pulpit, richly carved in bas-relief, is built against one of the columns of the nave, and over the great door, beneath the rose-window, is a crucifix by Giotto. The most entire dismantling is of the high altar. There is nothing at all left in it but dust and defacement, and the church looks desolate and forlorn, though it is one of the grandest in size and proportion, and contains so many treasures.

In the green cloister was a man sitting in a stall selling rosaires. He offered me 'The Tears of St Job', each tear crystallised into a bead, with a little cross, and I bought them out of love for that patient man, and in memory of Santa Maria Novella.

Uffizi Gallery

We then wandered to the Uffizi. I looked long at the Holy Family by Michel Angelo, and now I am convinced that Mr Ware is distraught on that point of the Madonna. It is painfully, uncomely, and expresses nothing of what he so extravagantly descants. It is a Madonna of his own fancy that he writes about.

Luini's beautiful Herodias' Daughter is very much in Leonardo da Vinci's style. When shall I have seen all the chefs-d'oeuvre of the Tribune, I wonder?

In another room I met the cold, disagreeable, handsome Alfieri, whose hard blue eyes are terrible from lack of all human kindliness of sentiment. Rousseau is much more genial, though by no means attractive; and Madame de Sevigné is lovely, by Mignard. So we went on till we came to Sasso Ferrato's Madonna of the blue hood. It is most tender and sweet, yet cannot be called the Adolorata. There is no sword in her heart, but only a pensive thought. Her exquisite mouth has never quivered with unutterable woe, and he shaded eyes have still the capacity to weep - not like Perugino's Mary's, drained of tears.

We were so fortunate as to find the Hall of Bronzes open, and we saw at last John of Bologna's original Mercury. It certainly is the Mercury of Mercurys. Such an airy flight was never before or since represented in bronze, marble, or whatever substance. He is trhown upon the air completely, and is airier for the bronze. A plaster cast carries a heaviness with it, besides that casts do not often give a true idea of the original. Sometimes they do. Michel Angelo's Lorenzo de Medici, and his Day and Night, and the noble Minderva Medica are really shadowed forth by the Crystal Palace casts: but they are the finest in the world. Ah, this Mercury! He is a winged Thought - fit messenger of the gods. The little Zephyr, who puffs beneath his imponderable foot, has no more work to do than if he were blowing a bubble. He will be gone quite out of sight in an instant - so exquisitely poised, with pointed finger, and head thrown back, and form turned, like a lovely, slender, voluted shell.

Benvenuto Cellini's first wax-model of Perseus was beneath a glass shade. The statue is far better, and the model is only a statuette. There is also a bronze model. His superb hemlmet and shield, made for Francis I, we saw, covered all over with small figures, - the helmet surmounted with a dragin chiselled with finest finish, in all its scales and horrors. It was deeply intersting, too, to see the bronze bas-relief which Ghiberti executed for a specimen of his capacity to make the gates of the Baptistery. It is the sacrifice of Abraham. There is also an exceedingly beautiful small statue of David, by Donatello. He has killed Goliath, and stands musing. On his head is a shepherd's graceful bonnet, with a rather broad brim, and a wreath round the crown; and he has such a simple, stripling air, so without triumph at his great exploit - he stands so musically, so gently, that he pronounces himself the sweet Psalmist of Israel, rather than the conqueror of a giant. There is force in his delicacy, but it is the force of genius, and not of physique. I have seen nothing of Donatelli that captivated me entirely before.

In the inner hall of very ancient bronzes are rare Etruscan treasures [now in the Archeological Museum]; and among them a Chimera of great antiquity, still perfect, except its tail, which is modern and a serpent. The principal head is that of a lion; and a goat's head shoots up quite unseasonably from behind the lion's.

A statue of a youth found at Pesaro is fine, and curious, from the puzzle it has proved to be to the wise. No one can decide whether it be Bacchus, Apollo, Mercury, or what. It is now called 'The Idol'. A robed figure, found in the vale of the Sanguinetto, on the shores of Thrasymene, has all the interest attached to that spot, besides being an admirable work. I saw there the very niellos from which the art of engraving originated, and they looked like delicate etchings on silver - slightly shaded outlines. In the same case were two enormous rings, with the largest rubies that I think were ever put in rings. They must have been for the thumb. In the British Regalia there is one as large, but not in a ring. There were a great many heads of Roman standards, the most memorable of which was the eagle of the twenty-fourth legion. We had not seen half, when we were hurried out, because the hour for shutting the gallery had arrived unawares. But before we left the western side, we went to see Michael Angelo's Bacchus and Faun.

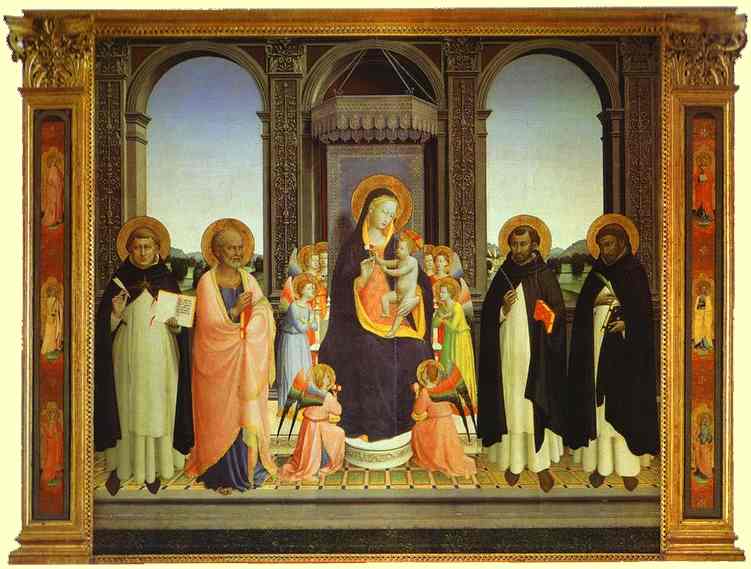

In the afternoon we visited churches - first Santo Spirito, close by us. The interior is grand, with its rows of columns and lofty, arched aisles, extending round the high altar. The high altar and choir are contained within a superb balustrade of precious marbles and bronze, surmounted by six angels in marble, St John and the Madonna. The altar is inlaid with pietre dure, in flowers and birds and arabesques, and the baldecchino is also ornamented with mosaics. The church is the best work of Brunelleschi. Entirely round the aisles are chapels, and many good pictures in them, and near the entrance is a copy of Michel Angelo's Pieta of St Peters, and one also of his St John of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. I became acquainted there with a new old painter, Piero di Losimo - new to me, of course, I mean; and I saw a Madonna and Saints by Filippo Lippi - the child Jesus reaching down to touch a cross which little John holds in his hands - all very noble and lovely; also a Madonna and four Saints by Giotto, the saints beautiful - the whole picture worthy of study. An Annunciation, by Botticelli, differs from all the paintings of his I have known. The faces of the angel and Mary are round and soft, instead of thin and meagre and hard, and what is called the motive of the picture is, as usual, sincere and solemn. He allows himself here a little beauty of form, isntead of regarding the expression of devoutness merely.

A Madonna and Saints, by Perugino,

fascinated me by the face of Mary - very like the adoring

mother in the

Pitti Palace - a face he could not repeat too often, for it is

of the noblest

type. While we were walking aout, the priests and monks of the

order of

St Augustine, who have a convent attached, came in a

procession from the

sacristy, and knelt down in their sweeping black robes upon

the marble

pavement, in two lines, one behind the other, and chanted

aloud their Ave

Maria. It was a wonderful picture. We afterward went into the

cloisters,

in the centre of which was an enchanting lawn, with shrubbery

and fragrant

flowers, in profound quiet, and wide, arched loggie around, in

which to

walk and muse, and only the sky above for prospect. What a

chance and persuasion

to be holy have these men in outward appliances; yet how

signally it often

fails, and what a comment it is upon man's arrangements, when

he presumes

to improve upon God's plans! What looks so woundrous, wondrous

fair, His

providence teaches us to fear. The wondrous fair that can

alone be trusted

meets neither the eye nor the ear nor the touch. He has

removed it from

all possibility of harm or change. Angels only are fit to live

as monks

pretende to live, and hence all the sin and woe. The relations

of husband,

wife, father, mother, brother, and sister must be filled by

human beings,

because Infinite wisdom designed the family as best for man.

It is singular

that in monasteries and all communities strictly of men, one

always has

a sense of a great want - an emptiness, and an absence of

thorough order

and nicety. They never seem clean; the beauty of holiness and

cleanliness,

which is next to godliness, are lacking. I have a shuddering

perception

of this whenever I am within their precints, though I cannot

tell or now

* * * *

Santa Annunziata

The Piazza of the Santissima Annunziata

Piazza Santissima

Annunziata

July 6th. - This morning we went to the Santa Annunziata. It stands in a large piazza, adorned by a noble equestrian statue of Ferdinand I, who is gazing up at a palace with a most earnest expression - and both palace and statue are set to music by Mr Browning in 'The Statue and the Bust'. It is the old Riccardi Palace, and what is now called the Riccardi in the Via Larga was then the Medici Palace, where the Grand Duke Ferdinand lived and had his Feast, at which the 'one word' passed, heard only by the bridegroom; from which came all mer misery. There are two fountains in the piazza, and the church extends along the whole of one side of it. Another side is filled with the Foundling Hospital, which has an arched loggia, and in the lunettes beneath are frescoes. There is also an arched loggia to the building on the third side, giving the square a very stately aspect. Entering the door of the Santa Annunziata, we were in an open court, surrounded by cloisters, in which were frescoes on the walls, by Pontormo, Andrea del Sarto, and Rossi, They are considered very precious, evidently, for they are enclosed in plate-glass, to keep them from the weather. Pontormo's I like best. He is grander than Andrea del Sarto ever is, and was his pupil. The interior of the church is magnificent, the roof exceedingly rich, and the gold upon it is in the utmost sheen and splendor. There are no remarkable altar paintings, except two good ones by Perugineo, especially an Assumption, with lovely angels. In the chapel of John of Bologna are six bronze bas-reliefs, by him, and a bronze crucifix, which are all admirable.

The high altar is of solid silver, with a great many reliefs, and a silver tabernacle surmounts it. The chapel of the Annunziata is as gorgeous as it can be made. It holds the miraculous picture painted by the angels, as the people truly believe. Eight thousand pounds have just been spent for a new crown for this angelic portrait; but it is so sacred that it is kept veiled, excepting on one or two particular occasions in the year, and we could not see it to-day. [Now always visible.] This shrine is erected in a corner of the nave, and climbs up into a Gothic point, with a multitude of angels, and wreaths, and ornaments. As many as fifty very large, ever-burning lamps hang from the roof above it, all of silver, and silver vases of silver lilies stand on the silver altar. The people were kneeling within and around it in passionate adoration. One man stood slon long kissing the shrine and pressing hiw brow upon it, that he seemed fastened by some spell. Forlorn and wretched creatures looked up at the veiled painting as they would into heaven itself. There was no sham nor luke-warm prayer-mumbling in all the throng.

Engraving of Miracle of Blind Girl

Recovering her Sight at Santissima Annunziata

Incisione, Il miracolo

della ragazza

cieca che riacquista la vista alla Santissima Annunziata.

Alongside the chapel is an oratory, very rich with pietra-dura mosaics, emblems of the Virgin - roses, lilies, stars - and the floor is of marbles. Little stalls and tabernacles of beautiful forms surround it, and in some of them stand vases of jasper and precious stones. It is a wonderful oratory, and sanctified by devout homage, I am sure. From one of the transepts we found our way into the cloisters, in which the lunettes are all painted in fresco with events in the lives of the seven founders; and between each are portraits of distinguished members of this order, which was that of St Augustine. [It is its own Order of the 'Servi di Santa Maria', but was required, like the Brigittines, to observe the Rule St Augustine wrote for his sister's convent.] One of the frescoes in the cloisters is the Madonna of the Sack, by Andrea del Sarto, quite famous; but I was very much disappointed in it. Mary sits upon the ground, with the infant in her lap. Her face is round and full, without any divine expression. Joseph is seated on a sack, with a book. It has a certain free and flowing style; but even before being injured by time, I do not see how it could ever have been a great picture. I cannot discover Andrea del Sarto's merits.

Coming home, we went to the Palace of the Conte Cavaliere Giulio da Montauto, to inquire about his vila, which we think of taking; and then we returned through the open court of the Strozzi Palace, surrounded by stone columns and loggie. It looks eternal, like the others.

This morning messengers came from the Count, to say we could have his villa.

July 7th. - This morning I went with J to the Museum [the Specola Museum, founded by the Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Lorraine, opened to the public in 1775, is the oldest scientific museum in Europe, holding the largest collection of anatomical waxworks in the world, manufactured between 1770 and 1850 and over 3,500,000 animals, of which only 5,000 are on view to the public], and the rest of us to the Pitti Palace 29. By and by Mr Hawthorne and R joined J and me. J and I were faithfully looking at everything, and dying of fatigue. We had been through all the precious stones, marbles, quartzes, and granites. We had seen the great Carbuncle, and no diamonds, because they were all put up on the highest shelves; but sparkling garnets, mild, refreshing, emeralds, gorgeous amethysts, and endless varieties of opals and chalcedonies and onyxes. Then we saw specimens of all the fishes in the seas - then of all the insects, many of which were once living jewels - then of every kind of butterfly that had burst out of a chrysalis. Then we saw wax models of rare exotics and fruits, and a collection of stuffed birds; and the richest, most blazing, fiery splendors of gems, I found on throats of humming-birds. One had an amethystine breast, which I never saw before - others were of bright gold, going through all shades of orange to deep dahlia crimson - passing through fire to get to crimson - all gradations of blue, from turquoise to deep sapphire and midnight blue - and changes of shining emerald. There was a bird-of-paradise of rare beauty; and the parrots in a corner looked like a fierce autumnal sunset; and for the first time I saw here birds entirely of bright azure (not cobalt, like our bluebirds). Then we had another show of beauty and of color in the shells. There were two real pearls still upon the oyster where they grew, more beautiful than any in the British Museum, and lovely opally anutili, besides specimends of every other that has been created. We had stuffed animals also, and their skeletons, and wax models of interiors of animals, very curious and very horrid. * * * *

This extensive museum adjoins the grounds of the Pitti Palace 29, and is a part of the amusements of the Grand Duke, which he hospitably shares with the people; for every man, woman, and child in Florence can goi in freely from ten to three o'clock every day. His Grand Grace does allow of any chairs through the whole suite of rooms, and all who enter must go into each room in regular order; and not retrace their steps, though they may remain hours on the way. Being utterly weary, however, I sat down upon some stairs, where no sentinel was watching, as I could at the worst but be told to get up and move on. I was not disturbed.

July 8th. - This was a day when the Boboli Gardens are open 28, and I took R there to stay as long as she liked. She fetched her jump-rope, and her doll Daisy in her little chair, and her fan. (It is but a few steps from Casa del Bello.) She also took some bread for the swans, and I took a book. When we arrived at the Lake of the Swans, they were in high displeasure, striking out their snowy wings, and actually groaning with unmelodious noises. They were hungry, and scolding at a man who was going upon the island, demanding food of him. He threw them some green leaves, which they devoured, and then they turned their magnificent stte toward R, who was leaning on the balustrade. They ate her bread with satisfaction and dignity, and then sailed off, in full trim, and we proceeded to a lovely lawn, where were many wild-flowers; and after exhausting that, we found still another, where R jumped rope, after tying up her bouquets with grass. Doll Daisy sat radiant in her arm-chair, holding her little mamma's fan and nosegays. We had all the rustling, blossoming, fragrant garden of Eden to ourselves, and seemed alone on a new earth, after we left the lake. At last R found a dead butterfly, which she wished to give to J immediately, and so we came home. In the afternoon we drove out to Bellosguardo, to see Miss Blagden and tell her about taking the Count Montauto's villa, and she went with us to see it. It has forty rooms.

July 9th. - We celebrated our great day by going to San Marco 24, the home of Fra Angelico, where his finest pictures are kept. The church itself is not handsome, outside or inside. In one of the chapels there is a very ancient mosaic of the Virgin, with extended arms, and saints round her. The face and figure strangely reminded me of Mrs Siddons. Over the door is the famous crucifix by Giotto, which established his fame above Cimabue; but it was difficult to see it in the dim light, it was so 'high up-hung', though I greatly desired to examine it minutely. As far as I could discover, the expression of the head of Christ was very beautiful. In the chapel of the Salviati are many bronzes, and among them a St John Baptist and some bas-reliefs by John of Bologna. St John is a powerful figure, in the act of blessing. The reliefs are placed too high to be seen - how unaccountable foolish! I could only discern admirable figures, but no faces.

The chapel of the Holy Sacrament

is inlaid with marbles, and contains paintings by Pocetto and

a new tomb

to a Prince Poniatowski [Principe

Stanislao,

Principe Poniatowski in Polonia, Cavaliere dell’Ordine

dell’Aquila Bianca

dall’8-XII-1773, Cavaliere dell’Ordine di San Stanislao,

Cavaliere dell’Ordine

di Sant’Andrea di Russia, Comandante in Capo della Guardia del

Re di Polonia,

Gran Tesoriere della Corona in Lituania dal 1784 al 1791,

Starosta di Stryj

(*Varsavia 25-XI-1754, +Firenze 13-II-1833)

= 1831 Cassandra Luci,

figlia del

Cavaliere Angelo Luci, da Tivoli, vedova dal 1830 di

Vincenzo Venturini,

da Castelnuovo di Farfa, creduto morto nella Campagna

Napoleonica di Spagna

ma ritornato in Italia nel 1814 (*Roma 1785, +Firenze 1863)

Principe Stanislao

Poniatowski,

Angela Kauffman, Museo Stibbert, Firenze];

but except some grand and expressive frescoes of saints,

there was nothing

to interest us. The sacristan then took us to the cloister

and Chapter-house,

where were a few of Fra Angelico's works. In the

Chapter-house is a very

large Crucifixion by him, with a predella of saints, but it

was not equal

to many other of his frescoes; and I was told, to my

chagrin, that the

very best of all no ladies could see! not even the

illuminated missal.

[Today

women and men may see the frescoed cells, the Gallery, the

Michelozzi library.]

A French woman was copying his great Crucifixion; but I was

so immensely

disappointed and really heart-smitten to find I could not

get at the inner

treasures, that I hardly looked at that, or at any of

Pocetti's frescoes.

I was glad to walk up and down the cloisters, exactly where

Fra Angelico

himself had paced, while meditating angels, virgins and

saints, and living

his holy life. He must have consecrated the stones.

In the church, near the entrance, was a wooden image of Christ, sitting with bound hands, and the crown of thorns upon his head, from which blood was trickling over his figure. An expression of the utmost pain in both face and form. A great many candles were burning around this distressing object, and a crowd of people were kneeling before it; and the whole chapel was filled with offerings from the devout - silver and gold hearts without number, chains and all kinds of trinkets; and watches (!) were hung rount the neck and arms. It was the most extraordinary, repulsive, and even grotesque spectacle. Opposite, behind glass, was a painted wooden figure of the Nativity. The Virgin was dressed in white silk, starred with gold, and a blue cardinal, edged with gold lace; roundf her neck were several strings of oriental pearls, and in her bodice a heap of jewels and rosaries - on her fingers a dozen rings, and emerald and gold bracelets on her arms. The baby lay on cloth of gold, and every appurtenance was in this gaudy style . so unlike the manger and the unadorned young mother. But these people hear of Mary only as 'Queen of angels' and 'Mother of God', and as they do not read the Bible, they know nothing of her humble circumstances.

Finally, we went to the Uffizi, and in the Tribune I saw, for the first time, a picture by Rubens of Hercules between Pleasure and Wisdom. The figure of Pleasure is as big as a hogshead, and as fat as his Bacchus. It is truly laughable in itself; and as it is Venus, the contrast between it and the Venus de Medici, near by, makes it preposterous. One a delicate dream of beauty, and the other a large portion of the earth's substance. Rubens must sometimes have taken beer-barrels for models, and touched them off with arms and heads and legs. But the picture is so admirable that one feels exasperated. Titian's Venus is another conception. The Madonna of Perugino is noble and affecting; and the child on her knee of the loveliest grace, while St John the Baptist is grand and pensive. The expression of the whole picture is sad with mighty prophecy and prefigurement of sorrow and trial. Wonderful, wonderful is Perugino in manifesting this divine seriousness, and calm, grave acceptance of the Cross. At the other side stands St Sebastian, pierced with arrows for the sake of the lovely and holy babe, who is turning to St John. Again I looked earnestly at Michel Angelo's Holy Family, and Mary remains to me entirely without beauty, power, or charm of any kind.

The perfection of the form of the Venus de Medici impresses me more and more, and the face loses its first effect. From one point it is still sweet and dignified, but from others it is simple and simpering, I fear. It was evidently of secondary interest to Cleomenes to elaborate the face; or perhaps the face is not his.

July 12th. - To-day I went to see a villa three miles from Florence, highly recommended for situation and convenience and elegance; but I found it have been misrepresented, though it had orange and lemon trees, a vineyard, and delicious flowers. It was altogether inferior to Montauto, and I concluded I did not like it. I brought home a bouquet to Mr Hawthorne, which taught him all that odors could about Paradise; and while we were feeling rich with this nosegay, the bell rang, and a large gypsy-hat-shaped basket was presented, filled with fragrant and glorious flowers from the Villa Tassinari, with Miss Howorth's card. There were long branches of noisette rosebuds, half-bloomed; every shade of double carnations, each one an Arabic of sweetness; heliotrope in profusion, bringing the delicate, yet heavy richness of the tropics; rose and scarlet geraniums; spikes of the trumpet bignonia; a white blossom of the texture of the magnolia, with a scent bewildering in delightsomeness; oleanders, now in perfection; and many others, whose names I do not know, - all of them reposing upon a substruction of verbena, the odoriferous, which has such a spirit in its sweetness. Must not the Villa Tassinari be Eden itself?

Academy of Fine Arts, and Other Places

July 13th. -We went to the Academy of Arts 23 this morning. We wished to see the Perugino again. Mr Hawthorne though that, in the Pietà, the face of Mary has more depth of expression than in the Deposition of the Pitti. It certainly seems to express al; but this face appears to be of Mary after the first hours have passed, and she no longer gazes in agony to find if it be indeed true that he is dead - as in the larger picture. She here knows it but too well. The sword is deep in her soul, and there is no anguish of inquiry. It is all still and hopeless - an old and settled misery. They have all been sitting and standing here a long time, and no more ask, 'Can it be?' It is, and they must bear it as they best can. There is hardly a face in art to be seen like this one of Mary. I think I said of the Magdalen, when I saw it first, that she was not beautiful. But she is beautiful. I felt the other day so deeply the overpowering sentiment of her face, that I really quite disregarded her features. They are very noble, and her hair is rich and golden. Vast and passionate is her sorrow; but how different from the intimate sorrow of the Mother! I am tempted almost to say that no one equals Perugino, when I think of these two pictures, added to many others of his which I have now seen. In this hall of the Academy is a Descent from the Cross, and on the left, a group of Marys support the Madonna, who is fainting. And now I am ready to exclaim, that never before was painted such a form and face as the Virgin's here, while every face and form around her are preeminently lovely and powerful in expression. But the fainting Mother! She has seen the drooping head of her Son, as Joseph gently deposes it, and the sickness of death has come over her. She is drooping too, and will fall directly. A mortal paleness this instant spreads over her, and one perceives the failing of her too agonized consciousness, and the heavy, heavy weight of her form collapsing, and drawing down the encircling arms of her friends. It is a group tht might make any artist immortl, if he had done no more. The upper part of this Descent from the Cross is painted by Lippi. It seems to me that the adoring Mary in the Pitti, folding her hands over the infant; happy then, yet with a prophecy in her heart of something unspeakable in the future of her baby - is the same Mary who is fainting in the Descent, and upon recovering, gazes with such searching, tearful dismay in the Deposition - and finally, sits with the beloved form extended upon her knees, in this Pietà, completely bereaved. It is the same person - the same noble, grand, tender conception, which, I believe, has never been equalled by any painter in the world. Raphael is inimitable in happy Madonnas, lovely, pure, sacred young virgins; but Perugino, the old master, has alone portrayed the pathos, grandeur, and religion of beauty in the Adolorata. Raphael was not inclined to paint this subject, either because his fay, unclouded nature naturally avoided themes so sad, or because he saw tht Perugino had accomplished all that was to be desired in this kind. I cannot now remember any sad picture by Raphael.

We looked at Gentile da Fabriano's wonderful Epiphany, in which there is not one ordinary face in all the gorgeous group; and at Lippo Lippi's Coronation of the Virgin, crowned by the Eternal Father, with its exquisite predella, containing the annunciation of the death of the Madonna, a miracle of genius again; and I should not wonder if it were by Perugino, as he and Lippo Lippi did sometimes paint in the same composition together. I scribbled a miserable little sketch of it in my note-book. The tender reserve of Gabriel, the majestic sweetness of Mary as she takes the torch! Whence could come the inspiration of these men, if not straigth from heaven, where they sought it! They must have prayed before they drew a stroke, and then a host of angels guided their pencils. Could any one but an angel have painted his brother Gabriel in this predella?

Now-a-days the angels seem to be farther off, driven away by profane artists.

July 14th. - In the afternoon I drove with U and R and Ada to Bellosguardo to meet the young Count and his steward at the Villa Montauto, to make arrangements. The Count was resolved to speak English, and we had a rather confused interview, because he did not speak it very well; but I made him understand that we would go to the Villa on the first of August.

July 15th. - This morning we went to the Bargello 7, the old palace of the Podestà, hoping to get in to see its treasures, especially Giotto's Dante. We mounted its fine old staircase in the court, and, with a grate between us, talked with an officer, who said we could not go in without the custode, who was then to be found in the Riccardi Palace. All round the walls of the building were the arms of the various persons who had held the power, cut in stone, otherwise we were none the richer for our attempt. So we got admittance into the Church of La Badia 6, opposite the Bargello. The ceiling is of richly carved woods, and it is in the form of a Greek cross. There are two marble monuments by Mino da Fiesole, and a good china bas-relief of the Virgin by Luca della Robbia, and Filippo Lippi's best easel picture of the Madonna with angels, appearing to St Bernard. A beautiful light campanile belong to La Badia, which is always a graceful feature of the views of the city.

At the Uffizi 10, we found the bronze room open, and looked again at the Mercury of John of Bologna, and Benvenuti Cellini's colossal head of Cosmo I. The wings on the cap and feet of Mercury are superfluous, for he is absolute Wing. In the cabinet of ancient bronzes we looked at the small Etruscan groups which were mended by Benvenuto Cellini in the presence of Cosmo I, who was so fond of seeing him put on little legs, arms, and feet, that he hindered the progress of Perseus, by constantly demanding that he should work upon them at the Palace.

In the cabinet of gems, two crustal cups, with gold covers, were his, - the crystal exquisitely cut, and the covers enamelled, and adorned with gems. One would think he must have had the finger-tips of a fairy. How astonishing that the man who could model a demigod in his fair proportions, tossing him through the foundry in a thunder-gust, should also so compose his hand and eye as to fashion tiny figures for ladies' rings, brooches for Popes and Princes, in designs as delicate and gine as frost.work, with arabesques of spider-thread tenuity.

In the afternoon I took a drive

with Miss Blagden and U, and we went to the great silk

establishment of

Lombardi, in the Piazza Maria Antonia [now

Piazza dell'Independenza], which

seemed a

fine palace, and not a house of merchandise. Upon entering,

what was my

surprise to find ourselves in a room hung round with the

original drawings

of Raphael, Michel Angelo, Murillo and other masters! We

bought silk, and

the the grand Lombardi invited us up-stairs, 'to see', he

said, 'his little

Raphael'. Here were three fine drawing-rooms, a golden canopy,

a Virgin

and Child by Raphael - a simple, pure, lovely picture, in his

first style.

This was a wonder, to be sure! Where could he have obtained

them all, and

how! He asked us for 'our revered names', and begged us to

call at any

time to enjoy his treasures. It is plain enough, I suppose,

that he has

money, and that for money, enough of it, one can purchase even

a Raphael.

Princes are often rich only in masterpieces of genius, while

merchants

are rich in the gold that princes need, and so the exchange is

made. Happy

is Lombardi to know so well what money is good for. He has

made a shrine

for his precious 'little Raphael' - a tabernacle, perhaps of

pure gold,

which shows his appreciation of it. After this most unexpected

delight,

we drove to the Cascine, where all the beauty and fashion f

Florence were

abroad, walking and sitting in various splendid equipages,

listening to

glorious band of music. It was a scene one dreams of, but

seldom sees.

* * * * *

Pitti Palace

July 19th. - We went to-day to the Pitti Palace. I find that there are two portraits of Ippolito de Medici, one by Titian and one by Pontormo. Titian's is superb. He is in Hungarian dress, buttoned up to the throat, which is very becoming, when a handsome head and face are shut off in that way. He stands with a wonderful dignity and grace, and his features and stule of head are of fascinating beauty, though I am sure he is not a good man. He looks dark and treacherous, with a princely state, worthy of a higher character. The Madonna della Seggiola is a sumptuous flower of rainbow colours, all softened and blended. The child is grand, with his wonderful grey eyes looking into the future, pure and limpid as the twilight sky. And his mouth is the richest blossom of innocence, peace, and charity tht ever bloomed from the palette. This is in Raphael's third style, and the Madonna of the Grand Duke is in his second style, with reserved mouth and lily lids, half closed, like curved petals over the soul of her beauty. She has an air of having nothing more to do with the world, and so she does not look out upon it; henseforth pondering over her own heart. The soft, prophetic splendor of the Seggiola infant's eyes is not seen in this babe's. These are harder; but the head is noble.

While we were occupied with the pictures, the military band struck up in the Piazza before the Palace, as usual at that hour, and glorified the common day, and added life to the painted forms and faces. We came down and went into the magnificent cortile of the Palace, which Luca Pitti said might hold within it the Palazzo Strozzi; and walked round, listening to the music.

In the afternoon, J and I went to the Carmine, where the frescoes of Masaccio and Lippi fill one chapel. Michel Angelo and Raphael considered them worth studying and copying. St Paul visiting St Peter in prison, on a pilaster, resembles Raphael's St Paul's preaching at Athens, though Massaccio's stands with his back to the on-looker. Nero, commanding the death of St Paul, is a perfect Nero, an epitome of all the marbles of him. The grandeur, force, expression, and fire of these faded old frescoes are marvellous, while the outlines are hard. The drawing, also, is superb. The light was not good, and J was impatient, and could not conceive what I wished to stay in such a dismal place for. So I deferred my study of them, and we crossed the Arno by the Santa Trinità bridge, and went into the Church of the Santa Trinità to see Ghirlandaio's frescoes. But a priest came to tell me that the morning was the only good time for them, and I found I could distinguish nothing; so I looked at a singular wooden statue of Mary Magdalen, near the entrance. She is nude; but clothed in the torrents of hair, which flow round and envelop her figure like a mantle, excepting her wasted arms and feet. The face is profoundly woful, hollow, and word; with large, cavernous eyes of piteous appeal, and a mouth of great humility and contrition. Yet the features are perfectly beautiful, though so wasted. I could fancy the countenance, and build it up from these wrecks - fresh, round, happy, and brilliant. Now it is a shadow. It was a bold thought of the sculptor to venture such a statue, but it was evidently executed when an inward religious sentiment inspired artists, with no regard to outward comeliness. J was very naturally astonished that I could look a moment at anything so ugly, he said; for what could he, in the early morning of life and experience, have within him, to interpret such a face and figure? I should have lamented, if he had been attracted or impressed with it. One must at least live and love and fail to reach the ideal, to understand such a conception. J understoof better the glorious sunset over the Apennines, which was changing th Arno into jasper and chalcedony, and sending isles of the blest of purest gold, to float over the blue sea of space above; while San Miniato, toward the east, with its grove of solemn cypresses, became soft in a veil of rose-purple, which floated down over the palaces at the base of the transfigured hill, upon which the church stands. During one precious half-hour before the great alchymist disappears, there is no end of the splendors his parting glance throwns over every object. He has gone, and in a moment the mountains are no longer 'the Delectable', the isles of the blest are blots of ink, the domes and palaces dull stones and not jewels, and all is grey, except a deep radiance just above the bed of state. That remains, and often sends out rays of pale color that lose themselves in the purple black abysses, through which the stars, one by one, and suddenly in innumerable hosts, gleam out upon their watch.

July 22nd. - To-day I took the children with Ada to see the plate at the Pitti Palace 29, because we heard that some of it was designed and cut by Benvenuto Cellini and John of Bologna. We saw an entire service of gold, and another of silver, with plates, knives, forks, and spoons, and dishes enough for a dukedom, and épergues of lovely design, chased and jewelled. But all these were merely costly. There were, however, a few exquisite goblets and vases and cups enamelled and gemmed by Benvenuti Cellini, and a great many salvers covered with figures by John of Bologna, as well as a large niello by him, and crucifixes in gold, silver, bronze, ivory, and precious stones, by both. For gorgeousness. merely, there was a shrine three feet high, made entirely of gold, pearl, and precious stones, with little figures of coralline and jasper and amthyst; but we were hurried by the guard, and my memory of it all is only a confused sort of glory.

We went into the gardens after leaving the palace, to look at four unfinished statues by Michel Angelo, now in a grotto with other old marbles and busts. These unfinished works of Michel Angelo give me a more vivid sense of his mighty power, than even his finished statues. In them we see him struggling with the stone, and wrenching from it the forms imprisoned within. Byron sings of 'his chisel driven into the marble chaos, bidding Muses stop the waves in stone', and so we seem to see it plunging and delving in these Pitt blocks. It is more like Milton's description of creation than anything else.

July 23rd. - To-day Louisa and Annie Powers accompanied us to the Guadagni and Corsini galleries. That of the Guadagni is very small. There are many portraits by Sustermans, and one lovely Madonna by Raphae in his second style; pure, sacred, serene, without the deep richness of his third manner. But the gallery is particularly famous for the two very large landscapes by Salvator Rosa, to which a separate cabinet is assigned. There are groups of small figures in them, and the scene is a great wilderness with mighty trees. I had not time to become at all acquainted with them, for the young people did not feel interested; and so we proceeded to the Corsini, on the Lung'Arno. It is the richest private collection in Florence. We found the saloons covered with carpets - an unprecedented circumstance in galleries. There were beautiful pictures, and quite a crowd of 'Sweet Charleses' (as Mr Hawthorne calls Carlo Dolci), and I do not like his works, with one or two exceptions. His famous Poesie I do not fancy at all. Everything feminine is too sweet, except the Madonna in the Grand Duke's chamber in the Pitti, but some of his saints are fine, though too metallic. It was worth while to come here, if only to see Raphael's cartoon in pencil of his portrait of Julius II. It has all the immense power of will and thought of the oil-painting, and so far verifies Mr Powers' assertion, that color is not needful to expression. This drawing is of the size of life, and finished with the utmost nicety and truth. It is a wonder and a beauty and a lesson to observe how the greatest masters carefully and faithfully and patiently elaborated their work, never disdaining an exhaustive perfection in each item. What a vast labor is here, and not a line is omitted or hurried! It would seem as if Raphael had an eternity to work in, for he was never in haste; yet what an enormous amount he accomplished - dying too in early manhood! Michel Angelo, to be sure, did not show patience always, though he has left careful drawings. His genius seemed an Atè, lashing him with her brand often. Yet there sit the sublime prophets and sibyls in infinite calm; and the lovely form of Eve is the ideal of woman, delicate and new from the hand of the Creator, as if she peacefully dawned upon his mind, as he sat musing on primal beauty. There was a small copy of his Last Judgment, in brilliant color, as it originally blazed on the walls of the Sistine Chapel, before some of the figures were draped by order of the pseudo-modest Pope, who insisted upon the resurrection of jackets and breeches. The hues of this copy are a revelation to me of the dazzling splendor of all those Sistine frescoes, in their first freshness. How stupid and short-sighted to smoke and spoil such productions with candles and incense-vapors, instead of reverently learning from them how to worship! Their deepest significance sems to have been lost upon the age that produced them. Through the mist and smutch of centuries we grope for them, almost in vain. I shall like to see what is to supply their place.

As I think now of a picture of the Resurrection by Perugino, in the Vatican, and recall the perfectly beautiful and noble face of Raphael in early youth, as one of the sleeping soldiers, I perceive that Perugino must have taken him for a model for the noblest of his Madonnas - that of the Pitti Palace. I see the strong resemblance in the contour - the exquisite bow-like mouth, the moony eyelids, and the serene, smooth brow, so compact with mind. I wonder if any one ever noticed this.

a

a a

a a

a

Perugino

Madonna

Raphael

Self Portraits

In one of the saloons we saw a vase of marvellous beauty of design and execution - bronze, about two feet high. I exclaimed that it must be by Benvenuto Cellini, and the custode said it was so. It represents, in bas-relief, the triumph of Bacchus.

Ada tried to draw it on the spot, but in the midst the custode told her she must not do it, for it was forbidden. I suppose the Prince Corsini I suppose the Prince Corsini is afraid that some artist will attempt to imitate it, and then he would not have the only one in the world. But why should he? He cannot prevent my remembering it, however, so distinctly that I can sketch it here at home. The figures are of enchanting grace - and the baby Bacchus on the panther and the whole procession as perfect as possible.

After tea we took a walk to the Ducal Villa, going out of the Porta Romana, and making a great circuit, so that we entered the city again by the Porta San Miniato. The avenue of cypresses and other trees leading to the Villa itself was very pleasant, as R and I experienced the other day, with the beautiful hills on each side. U undertook to be our guide, but misled us between endless stone walls, from one opening of which, where a church stood, we caught a glimpse of the Val d'Arno, and then were again swallowed up, till we arrived unexpectedly at the gate of San Miniato. The moon rose during out walk, and wrapped us in silver-fire - which odd combination of words alone can convey an idea of the glowing splendor of the Italian moonlight. Upon entering the city, we crossed the Ponte Vecchio, so as to see the Arno flooded with light. Upon any one of the bridges over the Arno, at sunset, moonrise, or starlight, all poetry and visible art combine to make the scene wondrous, besides that nature lends a hand in the river, the mountains, and the sypress-crowned heights, immediately around Florence.

I wish I could seize something elusive and unsatisfacotry in the divine loveliness of this Italy, so as to express what I always feel when I look upon it. There is a dream-like quality in my enjoyment, and I cannot bring it home to a sober certainty. It is like the ghost of a very precious reality. It is something that has been, even while it is now that I have a sense of it. Italy is a land of monuments and those who builded them have long passed away. A mighty silence succeeds them. Even the people in the streets of to-day seem like puppets galvanized into motion, and the real, living, grand beings are no more. There is a pause in all rare achievement. The cunning hand, the unerring eye, are nowhere to be met with, though marvellous works attest their former existence. It would not be surprising, but far less strange than the present state of things, if all the masters in Art, in State, and in Science, who stand clothed in white marble in the Court of the Uffizi, were to descend from their pedestals and walk the streets of their beloved Flroence. They would be more fitting and proper to the place than those persons whom we meet to-day. The latter are, as it were, empty chrysalids - deserted shells. Something has scared away souls - and only autometons remainds. Perhaps the Medici were the cause of this death and void - the Medici, and then this present race of Grand Dukes. When a prince takes the form of a monkey, he ought to be deposed. The land seems catching its breath. It is not dead, but oppressed and suffocated. I cannot put my feeling into words, and I may as well not try to do so.

Or San Michele

July 28th. - To-day we went again to Or San Michele 12, and very exactly scrutinized the Tabernacle by Orgagna. It was built to contain a miracle-working picture of the Virgin. Or San Michele is one of the glories of Florence. It was once an open loggia, - large arches, supported on pillars, a sort of mart. In one corner hung this picture, which was of such repute and efficacy, that there was a perpetual throng about it. Then Orgagna raised it for this magnificent shrine; and finally the ooggia was closed up, and became a church, and windows were put in of the richest painted glass, and the pillars were covered with frescoes, lately again brought to light. The various Guilds of the city have a hall over the church, and the building is lofty and nobel; and outside, around it, are arched stalls, conatining masterpieces of sculpture. Above the niches are medallions by Luca della Robbia, and, at this moment, all these niches and medallions are undergoing a thorough cleansing and repairing, in gorgeous style. Six are already finished, and each is different from the others in its mosaic of marbles, precious stones, and gold. One of them is of lapis-lazuli, with golden stars - like a midnight starry sky.

The tabernacle is of white marble, and bas-reliefs are sculptured over it. Some of them have backgounds of lapis-lazuli, upon which the figures are well defined, and there are borders to the separate groups of inlaid pietre dure and gold. It is Gothic in form, and every pinnacle flames with the fire of genius, held fast by cunning workmanship; and statuettes throng about it, angels, saints, virtues, prophets, all rising to one central point, upon which stands the archangel Michael, the power of God, embodied, fit apex to such a shrine. The subjects of the reliefs are the never-wearying incidents in the life of the Madonna and of Christ, and behind is a very large sculpture of the death of the Virgin, with her Assumption above. This death and the Assumption are among the most beautiful of the Catholic legends, and give the noblest field for the display of art. The dying holy mother - the grave and stately apostles - the rush of wings and flutter of robes, the glorified, enraptured ascended one - the trumpets, viols, dulcimers, and harps, weaving the air into an involved web of melodious ecstasy - the Eternal Father opening the heavens to look down, and the Dove, with outspread wings - or Christ in his own form, ready with the crown for Mary's brow - what more could mortal artist wish for the inspiration of his genius and for its expression?

I wish now that all the masterpieces of the past could be thoroughly restored in the way in which the Florentines are now restoring the exterior of Or San Michele. For now it is worth while, because, probably, no more barbarians will come to ravage Italy, and no more mad and stupid fanaticism will demolish works of art. Everything in architecture might be completely renovated in all old countries, though the divine frescoes and paintings must gradually vanish. But if we could only retain the Temples and Cathedrals, and renew their ruined portions while enough remains sound to indicate what they once were, what a glory it would be! The Campanile must never crumble away, and the Duomo must never lose one of its bits of inlay, and presently it must show a façade worthy of its heaped up grandeur in all other parts. Is there anything significant in the singular fact that scarcely one of the churches puts on a fair face? I sometimes wish I could clear away all modern Rome, and set out again the temples and palaces of the ancient city. But we cannot hold on to those marvellous productions, and I doubt not there is a good reason why not. I should like to see what is to follow that will be better than they. A better comprehension of Religion and Life may dedevlope a hidden power of art; though, really, if I would see more divine faces than those of Perugino and Raphael, I think I must ascend to another world, and not look into the future of this.

Toward sunset we drove out to the Villa Montauto, to take the inventory and keys. We found everything in order, all the muslin curtains in the bedrooms snowy and fresh, and an inhabitable air in the house. Without, the grounds and prospect were in princely state and beauty.

Bellosguardo. - Villa Montauto

August 6th, 1858. - We came to this delightful Villa on the 1st of August. * * * *

This evening there has been a superb sunset. At the northwest, over the mountains was a wonderful cloud, shaped exactly like a wing, of downy gold and purple and crimson tints, and of gigantic size, as one might fancy an archangel's to be. A truly feathery fleeciness pervaded the mighty pinion. As the twilight deepened, storm-clouds accumulated about the mountain, and presently vivid lightning flashed beneath the winf, which still, however, brooded in immovable calm over all the tumult, like the Spirit of God over chaos. In contrast to the rage and confusion of the elements in that quarter - toward the southeast, opposite, was a broad, golden Peace, which, by degrees, seemed to cncentrate and bloom into a large star, a flower of light (as I have heretofore called stars) - and it gleamed, undisturbed and unflickering, like the eye of a seraph; and was not that his wing on the other side?

August 7th. - The dawn was broken

by a violent wind, which sounded like the ocean in fiercest

anger. We seemed

not on the crest of a gentle Val d'Arno, but on the shores of

the northern

seas. Upon looking out, I found it did not rain, and the

atmosphere became

quiet enough after breakfast for U to go to her drawing lesson

in Florence

with Miss Bracken.

A Magician's Treasures

August 11th. - To-day Miss Blagden took us to see Mr Kirkup, the antiquary, artist, and magician. He lives directly upon the Arno, in an old palace of the Knights Templar 11. [George Eliot used Mr Kirkup and this palace for her heroine's father and home in Romola. Kirkup collected Dante manuscripts which were purchased by Lord Ashburnham's agent, Giovanni Libri, then were returned to the Laurentian Library. The palace was bombed in WWII.] He is of the age of the Wandering Jew, with snowy, silken hair and drifting beard; a delicate, elegant figure, handsome features, and fair, taper hands. His lives with only a tiny daughter, a little dark-eyed fairy, just fit to be a daughter of a magician. She was dressed in white muslin, and so delighted to see visitors that she kept up a continual musical laughter, varied with shrill shouts, as she played about us with her kitten. The kitten was very pretty and in wonderful harmony with the scene - a kind of familiar spirit of Mr Kirkup. There were two large apartments, filled with pictures, books, and curiosities, embroidered with the dust of a century. The gentleman had known Byron and many notable persons, of course, and on his walls are portraits of famous people, and sketched innumerable. He is rich in old manuscripts and missals, illuminated. A manuscript of the Divina Commedia he showed Mr Hawthorne with great pride, and I peeped at it too. It was on fine vellum, delicately written in black-letter by some learned monk, and brilliantly painted with pure colors, in that perfect way which it seems hopeless to try to imitate now-a-days. The unerring finish of these miniatures gives an idea of preternatural powers, and though the drawing is sometimes incorrect, it does not matter, for it is a part of the character of illuminations to have the quaint figures of not exact anatomy, just as stained glass becomes impertinent and vulgar, if one finds careful academic rules followed. These things are triumphs of color, not of form. A cathedral window must look like a jewelled ephod, at the first glance - a bewildering blaze of splendor. By and by, with earnest looking, the various tings unfold themselves into blessed faces and shapes of rudest lines, or rather of no lines, but bright blurs and passionate daubs of ruby, sapphire, and gold. What seemed a gem becomes an impossible foot or hand. An ecstasy or a sadness or a devoutness is somehow conveyed into the expression of the features, and the drapery is designed for color to lavish itself upon. When we hear of the angels being arrayed in light, we probably fancy a silver, white light. But it is no doubt light broken into the seven different hues rather, and these stained windows and missal paintings shadow those raiments. Somewhere in England I saw a painted window by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and it was an entire failure, for he had designed a regular picture of some scene. Who wishes to have a cathedral lighted by an elaborated, correct, academical composition? We do not feel patient to observe a set purpose, because then form intrudes, and we must have prisms, and, in the oldest colored glass, the forms are sharp-sided, like prisms. Dear me! how I have wandered from Mr Kirkup! He was very curious in relics of Dante, and he was one of those two persons who discovered the beautiful young Dante in the chapel of the Bargello, beneath the plaster, painted by Giotto, and he showed us his original tracing from it. The eye is wanting, for the workman found a nail driven through it, and instead of filing it down, or gently driving it in, he ruthlessly pulled it out, and the eye with it. But it is a delicately fine profile view of his face, with an aquiline nose, a mouth of pure curves and infinite melancholy, and clear, arched brow - stately, proud, but sweet also, then. The lips look ready to curl in scorn, however, and it a wonderfully haughty face.

7526 Firenze - Museo Nazionale - Ritratto di Dante Alighieri; affresco di Giotto

Mr Kirkup has also the very cast taken of his face after death. The long, heavy bitterness of exile has drawn down the curves of his mouth in the plaster head. The cheeks are furrowed with pain and indigation. The angelico riso of the divine Beatrice has not been able to smooth out of his countenance the stern anguish of his heart at the very last even. Perhaps he did not love quite enough and hated too much, and so his fate mastered him, and not he his fate. It seems as if nations made a point of putting all their greatest men to despair - completely desolating the earth for them; and them, when fame can be nothing to them, when they can no longer suffer, or feel joy or favor, worldly wrong or neglect, at the safe distance of a century or two, behold how thickly fall the honors! How the heavens are fretted with pinnacles raised to their memories, and over their remains; their remains indeed! How cathedrals are crowded with their monuments! how cities fight for their bones! how Genius prays to cut out their glory in marble, or emblazon it upon canvas, or fresco it on walls! It would seem as it the illustrious were obliged to compromise the matter, and that the account stood in this way:

For a given quantity of posthumous homage I must submit to pay,

One starved, houseless body -How costly then, is earthly renown! Often just when every heart and purse are open, the kind angel of death removes the sufferer 'beyond the utmost scope and vision of calamity'. There is doubtless a meaning in this, and it is best for the victim, though not for those who wrong him, certainly.

One broken, desolate heart -

A life wretched from calumny -

An indefinite amount of utter neglect -

A total want of appreciation -

Imprisonment in cells and madhouses -

Subjection to the Torture, and

Dreary, prolonged, exile!

The magician has also a mystical, nagical contrivance, with a landy inside, not then in working-order, reminding me of the conjurations of the wizard Cornelius. Mr Kirkup is also a magnetiser, and his little Imogen is a medium, so that he converses through her with dead emperors, and discovers how they have been poisoned and otherwise ill-treated while on earth.

August 13th. - To-day I went to Florence alone, quite early, so as to go to Santa Trinità 16, while the light was good for Ghirlandaio's frescoes. Out villa is but fifteen minutes from the city gate. I had a very nice chance; for the morning sun poured through a window of the clerestory, directly into the chapel. But the frescoes are excessively defaced. The Death of St Francis is better preserved than the rest. I saw the youth, in the group behind the child raised from the dead, who was called 'Il Bello' on account of his eminent beauty. In the upper compartment there are other portraits, which I could not well see, so high up as they are.