FLORIN WEBSITE ©

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO

ASSOCIATION, 1997-2007: FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || BIBLIOTECA E

BOTTEGA FIORETTA MAZZEI || ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING || FLORENCE IN

SEPIA || BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI

AND

GEOFFREY CHAUCER || E-BOOKS || ANGLO-ITALIAN STUDIES || CITY

AND BOOK I,II, III, IV || NON-PROFIT

GUIDE TO COMMERCE IN FLORENCE || AUREO ANELLO,

CATALOGUE || Paper given at Armstrong

Browning Library, Baylor University, 5 March 2006, and at

the Harold Acton Library, British Institute of Florence, 5

July 2006, celebrating EBB's Bicentennial (1806-1861), and

dedicated to Stephen Prickett, Director, The Armstrong

Browning Library, and Michael Meredith, President, The

Browning Society. The images are compressed and can be

copied with a left mouse click, then downloaded into an

empty Word or html file to view at their normal size.

AN OLD YELLOW BOOK: THE DOCUMENTS AND MONUMENTS IN THE

CASE

THE DEATH AND BURIAL OF

ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING

y story begins

and ends in the Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery in

Florence. In Elizabeth's day and at her funeral, 1 July 1861,

this is how it looked, nestled by the wall and gate Arnolfo di

Cambio had built. Gathered about her coffin were Robert and

Pennini, widower and orphan, Isa Blagden, Robert Bulwer-Lytton,

Kate Field, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, the Powers, the Storys,

but no carriage was dispatched to bring Walter Savage Landor.

y story begins

and ends in the Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery in

Florence. In Elizabeth's day and at her funeral, 1 July 1861,

this is how it looked, nestled by the wall and gate Arnolfo di

Cambio had built. Gathered about her coffin were Robert and

Pennini, widower and orphan, Isa Blagden, Robert Bulwer-Lytton,

Kate Field, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, the Powers, the Storys,

but no carriage was dispatched to bring Walter Savage Landor.

and this is

how Elizabeth had described the burial of Lily Cottrell.

And here among the English tombs

In Tuscan ground we lay her,

While the blue Tuscan sky endomes

Our English words of prayer.

The Ring and the Book declares 'But Art may

tell a truth/ Obliquely'. Here in Italy murder mysteries,

published in paperback, are called 'gialli', yellow books.

Robert had bought in the San Lorenzo Market in June of 1860,

'The Old Yellow Book' consisting of a gathering of documents

bound in vellum about a Roman trial that took place in Arezzo

in the Renaissance, where a husband murdered his wife. He

brought that book home joyously, liberatingly, tossing it up

in the air and catching it by the great gold-leafed framed

mirror in Casa Guidi's salone. But Elizabeth was not amused

with his obsessing on it, begging him to put the book away.

Let us turn the tables on Robert and investigate his wife's

death, as if in such a 'giallo' as that which he bought,

compiling together the documents in the case. Years ago, Mary

Beckinsale remarked to me that it would be important to see

the pharmacy prescriptions in Florence concerning EBB's

laudanum dosage, she believing Robert overdosed Elizabeth. For

Robert's poetic themes are so often of husbands who kill their

wives: The Ring and the Book and 'My Last Duchess',

and men their mistresses, 'Porphyria's Lover', or of an Andrea

del Sarto who feels his wife, his model for the Madonna,

Lucrezia del Fede, has blocked him from becoming a

Michelangelo, Raphaelo or Leonardo, this, the painting now in

two in the Pitti which Robert knew,

while the poem that attracted Elizabeth to Robert in

the first place was his youthful Paracelsus,

celebrating the inventor of her beloved - and deadly -

laudanum, and celebrating, too, what Robert would come to

hate, a belief in manifestations of the after-life. Later,

their child, Pen, will protest his mother taking so much

medicine, the opium, the cod-liver oil, the ass's milk (Arabella

I.530).

We need to examine Robert's poetry in the light of reality,

his fiction and their fact. For The Ring and the Book

is excellent camouflage. Ernest Jones in Oedipus and

Hamlet noted in a mere footnote that the dream within a

dream, like the play within the play, is the truth, and the

surrounding dream and surrounding play are the lie. If this is

so, Robert's 'lie' is his love, the lilied Ring by the

Castellani brothers, the 'aureo anello' of the Casa Guidi

plaque by Niccolò Tommaseo, not even using Elizabeth's poetry,

but instead the arts crafted by male goldsmiths and poets (I,

opening and closing lines, XII, ending lines); while the truth

is the Book found one morning in a market stall in San

Lorenzo, which is not fiction, but fact, the documents

concerning a Renaissance murder trial, safely displaced in

time, a 'Distant Mirror' deflecting us from his own Victorian

moment in history, Browning himself reiterating it as being

'pure crude fact/ Secreted from man's life'. However, scholars

have found that his Ring

and the Book departs from the Old Yellow Book. The

trial hinges on whether Pompilia is literate or not, if not

she is innocent and Franceschini has concocted the letters to

justify his murder of her. Scholars find that, in fact,

neither Pompilia nor Caponsacchi were innocent, nor was

Franceschini as evil as The

Ring and the Book has him. This leads us to an

interesting algebra, if we have equivalences between

Pompilia/Elizabeth and Guido/Robert. If Pompilia/Elizabeth is

illiterate then Guido/Robert is guilty and is the writer of

'her' letters, while if Pompilia/Elizabeth is literate, her

letters being her own, then Guido/Robert is wronged and

victim. Two things occupied much time in the Browning

household, the dressing of Elizabeth's and Pen's spaniel curls

for public show, the much writing of letters and poems, the

letters needing to be posted, the poems to be published. It is

undeniable that Elizabeth is literate, knowledgeable in fact,

in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, Italian and other languages

as well as English. But she in turn split herself into two in

Aurora Leigh, Marian

Erle, her own look-alike with spaniel curls, who is innocent

and uneducated, and Aurora Leigh, the woman writer. Which of

all these is Pompilia?

This study of Elizabeth's death and burial will go

to primary sources, much as did Robert with The Old Yellow

Book. Modern biographies of Elizabeth gloss over details

that were still known to witnesses to her life such as Kate

Field, and Mrs Sutherland Orr, and in the copious letters

Elizabeth wrote to her family members and others, and the

archival documents in the case. This study will rely on

archival documents, mostly unpublished, of the Swiss

Evangelical Reformed Church, the Letters edited by Frederic

Kenyon, Paul Landis, Philip Kelly and Scott Lewis, and the

detailed biographies of the Brownings written long, long ago

by Mrs Sutherland Orr, who was Lord Leighton's sister (she

being specifically commissioned to deflect the suspicion

concerning Robert's ancestry as Jewish, which she tackles in

her first paragraph, in her offical biography of him,

discounting it), Lilian Whiting and Jeannette Marks.

Elizabeth had written great love poetry to Robert

for which she is ever remembered, creating of the couple the

icon of ideal married love, who now lie asunder, she in

Florence, he in Westminster Abbey: she prophesying her romance

with him by referring to his Bells and Pomegranates

in Lady Geraldine's Courtship; crafting her exquisite

sonnet cycle in secret from Robert because of his tactlessness

concerning women's writing; playing as if a fugue with Pippa

Passes in the child's song, 'O bella libertà', and then

presenting their own child Pen, in Casa Guidi Windows,

a poem which, like the red, white and green flag, and the

colours of the Casa Guidi salone, the Austrians had banned (Arabella,

II.9);

and, in the best-selling epic poem as novel romance,

Aurora Leigh VI.562-565, again she presents their

child, as like some pomegranate, again paying tribute to

Robert's poetry published in his Bells and Pomegranates; as well as the

Wimpole Street love letters between herself and Robert, filled

with references to poppies and to Aaron's Bells and Pomegranates,

that Pen would later publish, following the publication by

Robert of Elizabeth's Sonnets from the Portuguese.

The story of the exquisite Petrarchan sonnets,

probably the best ever written, is heart-rending. Robert later

tells Julia Wedgewood of seeing them for the first time in the

summer of 1849, following Pen's birth and during their stay in

Bagni di Lucca.

Yes, that was a strange, heavy

crown, that wreath of Sonnets, put on me one morning unawares,

three years after it had been twined, - all this delay because

I happened early to say something against putting one's loves

into verse; then again, I said something else on the other

side, one evening at Lucca, - and next morning she said

hesitatingly 'Do you know I once wrote some poems about you?'

- and then - 'There they are, if you care to see them', and

there was the little Book I have here - with the last Sonnet

dated two days before our marriage. How I see the gesture, and

hear the tones, - and, for the matter of that, see the window

at which I was standing, with the tall mimosa in front, and

the little church-court to the right (Arabella I.371),

a scene which Elizabeth drew.

In Sonnet 18/XVIII Elizabeth offered Robert a lock

of her hair, mentioning she had thought that they would

instead have been cut by the 'funeral shears':

I never gave a lock of hair away

To a man, dearest, except this

to thee,

Which now upon my fingers

throughfuly

I ring out to the full brown

length and say

'Take it' - My day of youth went

yesterday -

My hair no longer bounds to my

foot's glee,

Nor plant I it from rose or

myrtle tree,

As girls do, any more. It only

may

Now shade on two pale cheeks,

the mark of tears,

Taught drooping from the head

that hangs aside

Through sorrow's trick- I

thought the funeral shears

Would take this first; . . but

Love is justified -

Take it, thou, . . finding pure,

from all those years,

The kiss my mother left here

when she died.

Already, following the death of her brother, Edward,

heir to the Jamaican slave estates, following that of her

mother, Miss Mitford had given Elizabeth the spaniel Flush, so

like her as to be an alter ego. Flush had gone with

them on the elopement, realizing he must keep silent on the

stairs of Wimpole Street, then, at Petrarch's Vaucluse, had

dashed across the waterfall, being baptised, Elizabeth said,

'in Petrarch's name'. The English climate suited him, Italy's

did not. Poor Flush was to lose his curls to mange and

eventually die and be buried in Casa Guidi's cellars. To be

resurrected by the childless, surrogateless Virginia Woolf in

her Flush: A Biography. But Elizabeth now had this

other and most miraculous alter ego, the baby Pen,

whom she kept in long curls, who imitated her even to writing

a 'great poem' in 1855 with a heroine named Lucy Lee, for

which John Kenyon paid him a guinea. Elizabeth, the cripple,

in constant pain, could bask in the energy of Flush, forever

running away, and in Pen on his beautiful pony, as surrogate

selves. She even tells Arabella that she and Robert confuse

their names, addressing the child as Flush, the dog as

Wiedeman, and suggesting this is no longer proper, now that

Pen is baptised in the Swiss Evangelical Reformed Church (Arabella,

I.264).

When Pen was born and Robert's mother Sara Ann

Wiedeman died in March of 1849 Robert seems to have had a

mental breakdown, similar to the one just before the

elopement, and which he will seem also to have at the time of

Elizabeth's death. We catch him, depressed, saying gravely to

Elizabeth, in 1850, "Suppose we all kill ourselves tonight" (Arabella,

I.290). Elizabeth had the one successful pregnancy with Pen

but also suffered four miscarriages, endangering her life. The

doctors counselled that she and Robert live celibately - which

cannot have helped their domestic tranquillity. Elizabeth's

was the prophetic voice to the world: her poem, The Cry of

the Children, effecting changes in child labour laws

when it was read in Parliament in England, Dosteivsky's

brother, Michael, translating it into Russian; Massimo

D'Azeglio quoting from Casa Guidi Windows on the death

of Charles Albert in an address to the Piedmont Chamber of

Deputies in 1852, and Francesco Dall'Ongaro translating 'A

Court Lady', about Margaret Fuller's friend, the noble

Princess Belgioioso working in Garibaldi's hospitals, while

Arthur Hughes the Pre-Raphaelite would paint both 'The Court

Lady' and Aurora's rejection of Romney's suit. She champions a

black slave who murders her child in Runaway

Slave at Pilgrim's Point, she champions a self-taught

single mother, Marian Erle, a gypsy, in Aurora Leigh, both

victims of rape. We find Elizabeth jokingly mentioning

Robert's quarrelling in an 1852 letter to her sister Arabella

(Arabella, I.545). Her money, from her poetry and from

the ship the "David Lyon", was supporting the entire

household, husband, child, servants, dog, and an addiction to

laudanum. Robert and Elizabeth were to increasingly argue over

Pen, he wanting his son to be English, she wanting him 'to be

an intelligent human being, first of all. Time enough for

national distinctions!' (Arabella, I.289). We find Sophia Amelia Peabody Hawthorne, 8 June 1858,

describing how at Casa Guidi 'Mr Browning introduced the

subject of spiritism, and there was animated talk. Mr Browning

cannot believe and Mrs Browning cannot help believing'

(344-347).

Jealousy seems to have seized hold of Robert,

paralyzing him from his poetic career, if we read Andrea

del Sarto as a mirror of his marriage. Elizabeth quotes

in a letter to her sister Arabella in 1860 from an American

newspaper, the Boston Daily Evening Transcript:

Another figure one is almost

sure to meet on his little pony at four or five in the

afternoon in the . . . Pincian. With his long light curls, and

his gay little cap with a red feather stuck in the side. I do

not know a more interesting sight or a more lovely boy. As he

trots up the avenue with his father, or followed by his groom,

all who know him delight to greet him - His mother wrote

'Aurora Leigh' and his father is the author of 'Paracelsus'. (Arabella,

II.463)

A justified jealousy seems also to afflict

EBB, as, for instance, when she, being a woman, is forbidden

entry to the private library of the Gabinetto Vieusseux and

its newspapers, safe from the Grand Duke's and the Austrians'

censorship, which have to be filtered to her through Robert

who is not sympathetic to her political ideals, and when Queen

Victoria arranges that the Prince of Wales in Rome meet

Robert, rather than Elizabeth. She had escaped from the

sickroom of Wimpole Street, presided over by her father Edward

Barrett Moulton Barrett mourning the loss of his slave wealth,

to find herself still physically helpless, still enclosed in

sickrooms, now presided over by Robert, who carefully monitors

her letters and her conversations and administers her tincture

of laudanum drop by drop, then increases the dosage. She lives

under double censorship, political and spousal. She catches

glimpses of the freedom of Madame de

Staël, George Sand, Félicie de Fauveau, Margaret Fuller and Harriet Hosmer, but

keeps her vows to love, honour and obey Robert made that

fateful morning in St Marylebone Church. She upholds for both

of them the ideal of poetic love in lawful matrimony. When she

is proposed for Poet Laureate, she considers Robert the more

worthy.

But an unjustified jealousy afflicts her over Lily Wilson, her faithful maid who procured

her the laudanum she had been prescribed by physicians from

childhood, limiting the doses and stopping them almost

altogether to allow the successful pregnancy with Pen. When

Lily, married by the Brownings in haste to Ferdinando

Romagnoli, in both Florence, in a Church of England service,

and in Paris, in a Catholic one, bore yet another child, the

Brownings tolerated leaving one child in England, the other in

Italy, and separated husband and wife. Lily became paranoid

over Ferdinando being now with Annunziata her replacement, and

was dismissed. She would later, at Robert's arranging, take in

the irascible Walter Savage Landor as lodger in Via della

Chiesa. Elizabeth knew Aeschylus' work in Greek, translating

him and speaking of Agamemnon's children in her Sonnet V. Lily

called her two sons, so tragically raised apart, Orestes and

Pylades, planning to call a daughter, if one were born,

Electra. It was dangerous for Elizabeth that Lily (yet another

alter ego, her true

name also being Elizabeth), was no longer with her to protect

her.

In Elizabeth Barrett Browning's last letter, which breaks off

unfinished, Robert halting it, we witness exhaustion (Kenyon,

II.448-450). The terrible last

photographs taken in Rome show her with emaciated deathhead,

despite the crinoline and curls.

In 1860, posing with her son Penini, she could still

smile.

In 1861, the year of her death, we see a prematurely

aged Corinne in front of a painted backdrop of Rome's

Colosseum (II.533). She was only fifty-five, though pretending

to the even younger forty-five, and having packed into those

years the writing of an epic poem longer than Homer's Odyssey, marriage, a

child. In May of that year, Hans Christian Andersen visited

them, commenting on how ill Elizabeth looked (Arabella

II.536). Her last poem, 'North and South', was about him, for

the children played with Robert his Pied Piper of Hamelyn,

processing through the rooms, and listened to Andersen's Ugly

Duckling.

But between these two dates, 1860-1861, is also the

publication of her poem, 'A Musical

Instrument' in the Cornhill Magazine. Robert

felt Elizabeth's poetic gift had ended, saying to her brother

George in a letter written from Asolo, 22 October, 1889, 'the

publication of "Aurora Leigh" preceded by five years the death

of its writer - who was never likely to produce such another

work', he being her literary agent during their marriage and

following her death. But one of those last disparaged works

was illustrated by Frederic Leighton for the Cornhill

Magazine and this poem, 'A Musical Instrument', is of

interest as a meta-poem, a statement about her poetic craft

and life. It is also a poem in which Elizabeth takes up a

theme she has often used before, drawing on her classical and

Christian learning, on the 'Great God Pan'. Pan, we recall, is

that chimaera, part beast, part man, related to

centaurs, satyrs and fauns, EBB speaking of Flush as 'Faunus',

and echoing Milton on the death of the pagan Gods in 'The Morning

of Christ's Nativity', both borrowing from Plutarch's

'De oraculorum defectu' in her 'Great Pan is Dead', and the

Hawthornes noting that Robert is Donatello of the Marble

Faun.

This is Lord Leighton's fine illustration from the

July 1860 Cornhill Magazine:

And this is Elizabeth's poem, "A Musical

Instrument":

What was he doing, the great god

Pan,

Down in the reeds

by the river?

Spreading ruin and scattering

ban,

Splashing and paddling with

hoofs of a goat,

And breaking the golden lilies

afloat

With the dragon-fly

on the river.

He tore out a reed, the great god Pan,

From the deep

cool bed of the river:

The limpid water turbidly ran,

And the broken lilies a-dying

lay,

And the dragon-fly had fled

away,

Ere he brought it

out from the river.

High on the shore sat the great god Pan

While turbidly

flowed the river;

And hacked and hewed as a

great god can,

With his hard bleak steel at

the patient reed,

Till there was not a sign of

the leaf indeed

To prove it fresh

from the river.

He cut it short, did the great god Pan,

(How tall it

stood in the river!)

Then drew the pith, like the

heart of man

Steadily from the outside

ring,

And notched the poor dry empty

thing

In holes, as he

sat by the river.

. . .

Yet half a beast is the great god Pan,

To laugh as he

sits by the river,

Making a poet out of a man:

The true gods sigh for the

cost and pain, -

For the reed which grows

nevermore again

As a reed with

the reeds in the river.

The verse about cutting the reed evokes The

Runaway Slave at Pilgrim Point and the slashing at the

sugar cane by slaves with their machetes. Robert, at Bagni di

Lucca, would similarly swim in the river. In Pythagorean

teaching there are two kinds of musical instruments, the harp,

which is Reason, and the wind instrument, which is Nature,

about the world of procreation and sexuality. Yet in this poem

Elizabeth seems to be speaking of her life and its thwarted

sexuality as a sacrifice - which is killing her - for the sake

of her art. The poem is very close indeed in its verbal echoes

to her magnificent translation of Apuleius'

Cupid and Psyche, this section where Pan rescues Psyche from

her suicidal despair, telling her to love innocently. But if

so it is now re-written away from the Apuleian version towards

that in Ovid, where Pan seeks to rape a nymph, who becomes a

reed, which he then mutilates for his instrument upon which to

play.

She leaves further clues about this poem's meaning.

Thomas Adolphus Trollope in What I Remember (II.

175-179), his gossipy book about the Anglo-Florentines,

describes finding enclosed amongst Isa Blagden's letters,

one from Mrs Browning which is

of the highest interest.

. . .

'Dearest Isa, - Very gentle my

critic is; I am glad I got him out of you. But tell dear Mr

Trollope he is wrong nevertheless

. . . There is an inward reflection and refraction of the

heats of life . . . doubling pains and pleasures, doubling

therefore the motives (passions) of life. I have said

something of this in Aurora Leigh. Also there is a

passion for essential truth (as apprehended) and a necessity

for speaking it out at all risks, inconvenient to personal

peace. Add to this and much else the loss of the sweet

unconscious cool privacy among the 'reeds' . . . which I care

so much for - the loss of the privilege of being glad or

sorry, ill or well, without a 'notice.' . . . Yes! and be

sure, Isa, that the 'true gods sigh' and have reason to sigh,

for the cost and pain of it; sigh only . . . don't haggle over

the cost; don't grudge a crazia,

but . . . sigh, sigh . . . while they pay honestly. . . .

But he is a beast up to the

waist; yes, Mr Trollope, a beast. He is not a true god.

And I am neither god nor beast,

if you please - only a

Ba

Elizabeth's

comment about the 'passion for essential truth (as apprehended)

and a necessity for speaking it out at all risks, inconvenient

to personal peace' is in reference to the Greek concept she well

knew of parrhesia, the obligation

to speak the truth, at personal risk, for the common good, so

closely related to eleutheria,

to freedom. And this is the classic principle, discussed by I.F.

Stone in The Trial of

Socrates and by Michel Foucault in a lecture he gave at

the University of Colorado, Boulder, shortly before his death,

which underlies this somewhat iconoclastic paper.

We can see that Frederic

Leighton, friend to both Elizabeth and Robert, has brilliantly

understood her poem in his engraving. When Leighton in the following

year was to design Elizabeth's tomb he seems not refer to Pan

or to the other chimaera, but instead only to have it

abound with harps, Greek, Hebrew and Christian, in reference

to her great learning from her early childhood in Classics.

the Bible and theology. Yet his first and Greek harp has two

facing faces, one serene, the other distorted, which at first

I thought were meant for Tragedy and Comedy though I was

uneasy about that identification. Then, this morning, we

visited the Giardino Torrigiani in Florence, close to Casa

Guidi, where Elizabeth would visit and which Leighton would

know, where Isa Blagden and Frederic Tennyson, the Poet

Laureate's brother, would stay. And there is the god Pan, a

bust upon a stele, one side of its face distorted, the other

serence, the two profiles to be seen again on the Leighton

harp. While on the stele are garlands about panpipes.

Towards the end Elizabeth is deeply affected by her sister

Arabella's death from cancer, followed by that of Cavour's.

Robert is wanting to see his father and sister, living in

exile in Paris (his father had lost a legal suit for breach of

promise to marry a widow following the death of his wife,

forcing the family to live on the Continent). Elizabeth's

doctor, the Pole, Gresanowsky, warns Robert in Rome that

Elizabeth by no means may make this journey to Paris and

Elizabeth writes sadly to Arabella, 11 June, with this news

(II.536-538), concerned for its effect on Robert. She had

hoped her brothers could have come to meet them there. Then,

on 15 June, she again writes to Arabella, with more vivacity

and a long discourse on Christianity, including discussing her

opposition to dogmas such as the XXXIX Articles of the Church

of England (II.541-542).

Lilian Whiting wrote Kate Field's biography,

composing it from her letters, publishing it in Boston in 1900

as Kate Field: A Record. This is the eye-witness

account Kate, the young American journalist, gave in two

letters written to her aunt concerning Elizabeth Barrett

Browning's death and burial:

Florence, June 29th, 1861

I am sick, sick at heart, for

dear Mrs. Browning is dead. The news was as sudden as it is

dreadful, for though she has been quite ill for a week past,

yet her health has always been so feeble that I firmly

believed she would rally as of yore. . . Yesterday Mrs.

Browning said that she felt better, read a little in the

"Athenaeum" and saw Miss Blagden as late as eight o'clock in

the evening, who left her with but little misgiving. This

morning, at half-past four, she expired unconsciously to

herself with the words, "It is beautiful," upon her lips. Poor

Mr. Browning was entirely unprepared for the terrible blow.

When she raised herself to pronounce her dying words wherein

she expressed the glorious life which was opening upon her, he

thought it was simply a movement premonitory to coughing. I

have not seen him, but Miss Blagden, who is constantly with

him, says he is completely prostrated with grief. The poor boy

wanders about the house, sad, and disconsolate, hardly

realising that his angel mother is no more. We went to the

house the moment we heard of Mrs. Browning's death, but could

be of no use. All that we did was to buy flowers and

consecrate them by placing them around all that is left of one

who was too pure to remain longer in this world. They have cut

off all her hair, and the emaciated form was heart-rending to

look upon. I almost regret that I have seen her in death, only

that I do not wish to shun the house of mourning. . . .

I cannot help perceiving that Dr. Wilson, who was called in

owing to the absence of Gresanowsky, and who is most

forbidding in physiognomy and is said by some to be a humbug,

has hastened Mrs. Browning's death by resorting to a violent

practice which her weak body was thoroughly incapable of

enduring. He began by frightening her, telling her what a

fearful state her entire system was in, - a fine way to treat

an imaginative person. Gresanowsky knew her constitution, and

it does seem most unfortunate that he should have been absent.

Since the medical murder of Cavour, I have begun to distrust

all doctors in Italy. . . . (Whiting, 134-137)

I do not recall anywhere else it being said that not

only were Pen's curls cut off but so also were Elizabeth's.

That mirroring identity, so crucial to Elizabeth, shorn by the

'funeral shears'. We remember the story of Elizabeth being

upset because one day Robert had in a fit of fury cut off his

own hair.

Kate Field's account matches that given by Henry James in William Wetmore Story and His

Friends (II.61-65), and by other contemporary

accounts which note Robert saying at the time that Dr Wilson

had prescribed too much morphine, Elizabeth in her drug

euphoria speaking of the bedroom curtains as hung with

Hungarian colours (which are the same as Italian colours, the

red, white and green we know Elizabeth to have used for the

windows of Casa Guidi because banned by the Austrians).

Robert, who had written the dramatic poem Paracelsus about

laudanum's inventor, was knowledgeable about these opiate

drugs, more so than was Elizabeth, and it was he who

administered the drops. In all these accounts narrated by

others their common source is Robert, the sole witness to

Elizabeth's dying.

The body would have been brought from Casa Guidi to the

'English' Cemetery and laid on the huge cypress wood table

built in 1860 at the same time as was the Gate House and its

mortuary chapel, all using the cypress trees on the hill, all

these being still extant, though the chapel is now turned into

a library.

Kate Field continues:

Florence,

July 1, 1861

I have been completely upset for the last three

days, - the death of Mrs. Browning has unfitted me for doing

anything. We have just returned from her funeral. We have

seen all that is mortal of her buried in the beautiful

Protestant burial-ground outside of Florence's walls, . . .

The service was according to the Episcopal form. No

discourse. Her life had been a sermon; she needed no other.

It was agonizing to look on Mr. Browning - he seemed as

though he could hardly stand, and his face expressed the

most terrible grief. The poor boy stood beside him with

tears in his eyes, and when I glanced from them to the pall

where their loved one's remains lay, it seemed as though the

sorrow was too much to bear. I yearned to go to Mr. Browning

and weep with him that wept. The scene was made impressive

in spite of the ministery; it was very short, and we were

hurried away by Mr. Trollope. A lovely wreath of white

flowers and a laurel wreath were placed upon the coffin. The

funeral was managed by a friend of the Brownings, and so

managed that no one knew anything about anything. Orders

were given to the greatest confusion during the three days,

and up to this morning I was told that no ladies were to be

at the grave. However, Mr. Browning expressed a wish that

Miss Blagden should be present and all other friends that

desired to; therefore at the last moment I sent word to

those whom I knew would wish to attend, and in this way

there were sorrowing women to mourn for a great woman. The

funeral would have been meagre without them. I thought that

Mr. Landor ought to have been there, and had I known that

the service would have been so short would have gone for

him. The Storys came up from Leghorn; young Lytton, Mr.

Trollope, the Powers, and others paid their last tribute to

her memory (Whiting, 137-138).

Let

us turn to the entries concerning Elizabeth Barrett Browning's

burial for more clues. As Custodian of the Swiss-owned

'English' Cemetery I kept asking whether there were any more

documents concerning these burials, apart from one ledger

compiled in 1877 of the list of burials in alphabetic order.

Always it was said everything had been lost in the 1966

Florence Flood. Finally, these were handed over: two ledgers

created contemporaneously, and a third listing burials in

temporal order, created in 1877 from the previous records,

like the alphabetical register, and the receipts for the

funeral expenses and the payments to the grave-digger, which I

now share with you.

The Burial Registers

neither of which give her

status as married, nor her parentage, and not even her correct

age:

I.

II. The

duplicate volume of the above:

[Interestingly,

Pen's baptismal certificate in the same Swiss Evangelical

Church's Register tells us that it was performed on what would

be almost her death date, 28 June, 1849, she dying 29 June,

1861.]

III. The chronological listing of burials in the

Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery, compiled in 1877

from the previous records:

The Alphabetical Register, compiled in 1877 from the

previous records:

In all these documents Elizabeth's age is

given incorrectly as '45', rather than '55'. We recall that

she did not tell her husband she had visited the Battlefield

of Waterloo immediately following Napoleon's defeat, though

she describes a child loosed upon that same battlefield in Aurora

Leigh. (The English Cemetery has six participants in the

Battle of Waterloo, some of whom were Elizabeth's friends.)

Nor does her tomb give her birth date, only that of the year

of her death, 'O+B+1861'. Her initials are given, 'E+E+B', but

not her name, as if Robert penny-pinched on the payment to the

stonemason, who would have charged for every letter. Another

husband composed a lengthy poem at the death of his wife,

Caroline Napier, and paid for each letter of it to be engraved

on her tomb slab.1

The Funeral Expenses

IV. Signor L. Gilli, Inspector of the Cemetery, is

paid 271 paoli for the funeral of Elizabeth Barrett Browning

out of which he pays the tax to the English Church of 113

paoli. Apart from a pauper funeral this is the lowest amount

paid at this time for an adult funeral. Those of Charlotte,

Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorn, and of Theodore Parker

cost more than a 1000 paoli each.

V. Then Ferdinando Giorgi, Master Mason, is paid a

total of 760 lire toscani from Signor L. Gilli for the burial

of 16 persons, the first of which is #737, Elizabeth Barrett

Browning's.

Normally, Ferdinando Giorgi is paid 45 Tuscan lire a

burial. He gets 90 Tuscan lire for EBB's burial, number #737,

because he had to dig two graves, finding the first was

already priced while digging it. Which means the Swiss

Evangelical Church this time only got 68 paoli. I puzzled over

this payment for the digging of two graves. Had Robert had one

dug for himself when his time came? Had another body been

found in it while digging the first? Then I found the answer

to this question.

In

September of 1861, two months after Elizabeth's burial, Robert

Browning wrote from London to Isa Blagden in Florence about

moving his wife's body from one grave to another for a more

showy position to be used for Frederic Leighton's tomb for her:

. .

. Isa, may I ask you one favour? Will you, whenever these

dreadful preliminaries, the provisional removement, etc., when

they are proceeded with - will you do -- all you can - suggest

every regard to decency and proper feeling of the persons

concerned? I have a horror of that man of the graveyard, and

needless publicity and exposure - I rely on you, dearest friend

of ours, to at least lend us your influence when the time shall

come - a word may be invaluable. If there is any show made, or

gratification of strangers' curiosity, far better that I had

left the turf untouched. These things occur through sheer

thoughtlessess, carelessness, not anything worse, but the effect

is irreparable. I won't think of it - now - at least . . .

Earlier,

Elizabeth had noted Robert's great fear of cemeteries. He had

refused, for instance, to go to the funeral and burial of his

first cousin James Silverthorne, the witness at their wedding (Arabella I.490-91,494).

Nathaniel Hawthorne modeled the character of Donatello in The

Marble Faun on Robert Browning and vividly described his

horror of death.

Immediately after the funeral, Robert commissioned

the painting by Giorgio Mignaty of the Salone at Casa Guidi as

it was when she died, on finding the room could not be

photographed, perhaps by Longworth Powers, perhaps by the

Fratelli Alinari.

We recall that two of the Mignaty children,

Demetrio and Elena, are buried in the English Cemetery, one

with the inscription in Greek,2

and that the head of the beautiful but not faithful

Signora Mignaty was model for Hiram Powers' Greek Slave

about which Elizabeth wrote her powerful anti-slavery sonnet.

The American sculptor Hiram Powers, who had

been present with his wife Elizabeth at Elizabeth Barrett

Browning's funeral, is also buried in the English Cemetery,3 while Michele

Gordigiani, who painted the portraits of Elizabeth and Robert

and likewise that of Camille Cavour, whose death on June 6th Elizabeth so deeply mourned,

1858

had his studio just across the street, his

descendant, Francesca Gordigiani, still living there.

Robert Browning, who sculpted and who wrote poetry

on the ordering of tombs, who was himself indulging in

scultpure rather than poetry at the end of their marriage,

commissioned Frederic Leighton to design Elizabeth's tomb,

Francesco Giovannozzi to carry it out. Frederic Leighton

had studied at the Accademia di Belle Arti and would become

President of the Royal Academy. His earliest triumph had been

to paint what Elizabeth had already described in Casa

Guidi Windows, the 'Procession of Cimabue's Madonna from

Borgo Allegri to Santa Maria Novella', the huge canvas being

purchased by Queen Victoria when he was all of twenty-four.

Leighton, we noted, illustrated Elizabeth's final

poem to Pan, 'A Musical Instrument', when it was published in

the Cornhill Magazine in 1860 (175-179), the year

before her death. Leighton also illustrated George Eliot's Romola,

including the despicable Tito's return home to her, which both

author and artist set in the Via dei Bardi house of

Elizabeth's friend, Seymour Kirkup:

Robert, who similarly often went out at night,

leaving Elizabeth at home, after the initial years of marital

bliss, immediately following the funeral left Florence with

young Pen, accompanied by Isa Blagden. He proceeded to write The

Ring and the Book, the Aretine and Roman trial account

in verse about spousal abuse and murder, as if his own

confession, with Caponsacchi as if Robert being Elizabeth's

rescuer from the bondage of Wimpole Street, and with

Franceschini as if Robert, who as husband constantly

quarrelled publicly with his wife over politics, over

spiritualism, over their son, who carefully administered her

laudanum, and who, as the author of Paracelsus, the inventor of laudanum, may

have knowingly overdosed her, while blaming Dr Wilson for

doing so. If so, it is a kind of mercy killing, for he

carefully explains to everyone that she is unaware that she is

dying, only that she is in a state of euphoria from the drug.

Leighton Sketch Book, Royal Academy Library

__

__ __

__

Greek

Lyre

Christian

Harp

Hebrew

Harp

Tragedy and Comedy

Cross

Jubilee

with Broken Slave Shackle

Leighton's tomb for Elizabeth is a magnificent

monument. But Robert never saw it, never returned again to

Florence, though Pen did, living in the Torre di Antella,

seeking to make Casa Guidi a museum, searching out memorabilia

of his parents, which at his death were all dispersed in

auction sales. Leighton did return to Florence and did see the

work in progress, and was deeply angered by the changes made

to his design by Francesco Giovannozzi and tolerated by Count

Cotttrell. Lilian Whiting's biography of Kate Field, the young

American writer who had been present at that funeral, tells us

that on Christmas Day, 1864, nearly three and a half years

later than the funeral,

Mrs Browning's monument has not

yet been erected, but will shortly be so. Leighton, who was

intrusted by Mr. Browning with the design, was exceedingly and

very reasonably angry on coming here in the autumn to

superintend the erection of the monument, to find that the

sculptor had most unwarrantably changed divers parts of the

design. Some of these departures from his plan Leighton

insisted on having restored, and this has led to considerable

delay. And I should fear that the monument, when it is put up,

will not be wholly satisfactory to Mr. Browning or Mr.

Leighton (Whiting, 157).

Count Cottrell, whose title was given to him for his

services as Chamberlain by the Grand Duke of Lucca, had

refused to go to the English Cemetery at the burial of one of

his children there, Carlo Lodovico, Robert officiating for him

as chief mourner (Arabella,

II.322-323). In some of the earlier Letters to Arabella the relations between

the Cottrells and the Brownings became decidedly strained, for

Mary Trepsack had had her life savings conned from her and

lost in a bankruptcy by Cottrell relatives, partly through

Robert's actions, Elizabeth desperately trying to get

reparations paid to her in compensation while obeying Robert

in keeping secret from her brothers his involvement in the

case (Arabella

I.268-269, 271-272, 286, 305, 311, 349-350). Mary Trepsack was

the beloved freed slave in the Barrett Moulton Barrett entourage who had

paid for the publication of Elizabeth's second magnum opus, The Essay on Mind, in

1826; Elizabeth's first magnum opus, The Battle of Marathon, begun when she was

eleven, having been privately printed by her father in 1820.

Robert now put Count Cottrell in charge of overseeing his

wife's tomb in Florence.

Browning writes, in 1866,

to George Barrett, Elizabeth's younger and favourite brother

(284-5):

I feel very grateful indeed for your

letter, and all the kindness it is replete with. For the

monument, I am simply rejoiced that you like it. You know it was

just what I was able to accomplish in that direction, and no

more: I meant, - that had it been of pure gold it would have

gone no farther in the way of being a fit offering, - and on the

other hand, if my circumstances had only allowed me to put up a

wooden cross, that would have sufficed. But I was fortunate in

the sympathy of Leighton, and so, I hope, have been able perhaps

to manage that the little which is done, is on the whole well

done. I could not be on the spot and care for the execution

personally - and mistakes were made at first which have been

rectified since: but, by the photographs, I judge that

Leighton's work is adequately rendered, - and we must be

content.

Browning

writes again, in 1875, to George Moulton-Barrett (298), who

has been to see the tomb in Florence, noting in a letter to

Robert that it was already grimed and needing care (Sutherland Orr, 367-68):

You will certainly have wondered at the

delay in replying to your kind letter: it was occasioned by the

necessity of consulting with Leighton about the proper course to

take in a matter which concerned him so much. I am deeply

obliged to you for informing me about what I might else have

long remained in ignorance; and the particulars of the damage,

as well as the estimates of needful repair & expenditure are

just what I should have desired. I wish every fit measure to be

taken, and leave the whole in your most capable hands: but there

is this difficulty, - Leighton is very averse to the destruction

of his design by the substitution of black marble: he would

prefer the renewal of the old work, even if one needs to begin

again in another eleven years. Cannot this be managed? I wish it

were as easy to replace the coarse nature of the relic-mongers

by some more human and decent stuff, but that is

impossible. Would a more effectual railing be any use? or would

a cover, such as you mention as being made for the Demidoff

monument, answer the purpose here? You have such an advantage

over me who never saw the Tomb, that I accept your judgment,

whatever it may be. Leighton said he would prefer letting the

ornaments quite go, in process of time, and then

renewing them - that is, prefer this to substituting the black

stripe.

Elizabeth's

absence from her own tomb is strange. There is no medallion

portrait of her, only an ideal figure of Poesy, and we learn

from Robert's letter from the Athenaeum Club, January 19,

1863, to Isa Blagden that the Italians, through Cottrell,

sought to pre-empt Leighton's design, and in Robert's letter

to Frederic Leighton, August 20, 1863, that he had sent

portraits of Elizabeth to him, then he writes to Isa,

October 19, 1864, about Leighton's explosion concerning the

badness of the execution, and speaking of the portrait

medallion as altered, particularly as to the hair, to

falsely 'better' it.

It was fortunate indeed that I was saved from the

addition to my annoyances which I should have had to bear had

my journey been to Florence. Leighton writes to me that

nothing can be more impudently

bad than the execution of his designs - there has been no

pretence at imitating some of them - and the four (sic., for six) capitals

of the columns will have to be sawn off and carved afresh, -

also two of the medallions have to be cut out and replaced -

as infamous: while the third 'though indeed detestable is not

quite irremediable". The Profile is "less slovenly than the

rest", though open to many objections - "the hair, with that

designing of which I took great pains, is entirely different:

the fellow had the coolness to say that he thought I had

probably done the thing hastily without nature, and that he

had put up a plait, and done the thing afresh himself (if you

could see it!) - also, in the ear, "ho cercato di migliorare!" he added that he

had obtained from Cavalier Mathas [architect of the façade of

Santa Croce] and Count Cottrell the sanction to improve these

parts of the work - let us hope there is no truth in this.

Cottrell says he saw all the criticism I make, himself - but

that he thought it better to leave them to me to make, as the

mischief was irremediable"- On the contrary, Cottrell wrote to

me that it was "extremely well-executed", - and as he paid up

the last instalment, though not due till the work was really

erected, I have no sort of remedy. Don't say one word about

this - I won't have any wrangling over - literally - the

grave.

One can see in three of

Hiram Powers' son Longworth Powers' photographs, preserved in

the Gabinetto Vieusseux, the various stages of the tomb's

building, first the white marble base, then the columns, then

the whole.

Leighton

changed the other errors, but Robert allowed the false

portrait medallion to stand on the most visible part of the

tomb. Not only is Elizabeth's name absent from her tomb, but

so also is Frederic Leighton's, while

'FRANCESCO.GIOVANNOZZI.FECE' is sculpted onto its base. One

wonders who paid for the tomb: Browning? Or Leighton?

On it there are no lines from her poems. There

is not even her name, just the initials 'E+B+B'. Nor is there

her birth date, just the death date 'OB+1861+'. However,

it seems from sketches in the Royal Academy's Library that

Andrew Potter has so kindly sent me that Leighton conceived it

not as a classical sarcophagus so much as a medieval pilgrim

tomb with space under it for pilgrims to enter, like that of

Edward the Confessor's Tomb in Westminster Abbey. An aside: When

Elizabeth was preparing herself for the elopement with Robert,

she dared to go outside, to take walks, and on one of them

visited Westminster Abbey and its Poets' Croner where her

husband would come to be buried. This is how she described it,

31 July, 1846:

How grand - how solemn! Time itself seemed turned to

stone there! . . . we stood where the poets were laid - oh, it

is very fine - better than Laureateships and pensions. Do you

remember what is written on Spenser's monument - 'Here lyeth,

in expectation of the second coming of Jesus Christ, . .

Edmond Spenser, having given proof of his divine spirit in his

poems'.

Edward

the Confessor's Tomb,

Westminster Abbey

We find that

Leighton had intended a more true portrait on the tomb as he

originally conceived it, these drawings being supplied by the

Leighton House Museum from those in the Victoria and Albert

Museum, (he even shows a togaed Robert approaching it!),

with a

designated space for an inscription on it, perhaps with her

poetry.

In an earlier paper, I lamented the lack of the

major symbol Elizabeth and Robert shared in their poetry on

her tomb, that of the pomegranate.

It is my hope, if we can restore and landscape the 'English'

Cemetery, that we shall plant a pomegranate beside it. We have

already rectified the lack of her name with a stele by the

tomb.

Likewise we have sought to correct the absence of

her poetry on her tomb with its presence on the walls of the

Gatehouse's arch, unveiled last year by Dr Stephen Prickett at

our conference with the Gabinetto Vieusseux on the 'English'

Cemetery.

We remember,

too, that Emily Dickinson, America's

greatest poet, treasured a postcard of this tomb, and wrote of

it and Aurora Leigh in her lyric, 'The soul selects her

own society, Then shuts the door; On her divine majority,

obtrude no more. Unmoved she notes the chariot's pausing At her

low gate; Unmoved, an emperor is kneeling Upon her mat. I've

known her from an ample nation Choose one, Then shut the valves

of her attention Like stone'. She also wrote of Elizabeth

Barrett Browning's final volume (312):

Her -- "last Poems" --

Poets

-- ended --

Silver

-- perished -- with her Tongue --

Not

on Record -- bubbled other,

Flute

-- or Woman --

So

divine --

Not

unto its Summer -- Morning

Robin

-- uttered Half the Tune --

Gushed

too free for the Adoring --

From

the Anglo-Florentine --

Late

-- the Praise --

'Tis

dull -- conferring

On

the Head too High to Crown --

Diadem

-- or Ducal Showing --

Be

its Grave -- sufficient sign --

Nought

-- that We -- No Poet's Kinsman --

Suffocate

-- with easy woe --

What,

and if, Ourself a Bridegroom --

Put

Her down -- in Italy?

Mrs Sutherland Orr, in her official biography, Life and Letters of Robert

Browning, published in 1891, its frontispiece Pen's

painting of his father and giving copies of letters supplied

to her by Miss Sarianne Browning, tells us that Robert never

visited the tomb (Sutherland Orr, 367-68). And she is Lord

Leighton's sister.

Five years later than

Elizabeth's burial another grieving husband himself sculpted

his wife's tomb up in Fiesole to be beside that of Elizabeth.

Fanny, wife to Holman Hunt, died in Florence following

childbirth.

Holman Hunt's wife

modelling for John Keats' Isabella and the Pot of Basil.

and for her portrait during

her pregnancy in Florence.

He created for her an ark,

complete with dove and olive branch doing double duty as a

pelican in its piety, and adorned with lilies copied from

those on Elizabeth's tomb, which forever floats on waves

sculpted from marble, and he placed three scriptural

passages from Isaiah, the Gospels and the Song of Solomon,

one of these echoing Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnet

XXVII to her husband, within Florentine triangled roundels4:

WHEN

THOU

PASSEST

THRO

THE

WATERS

I

WILL BE WITH THEE

AND

THRO THE FLOODS

THEY

SHALL NOT

OVERFLOW

THEE

|

IT IS

I

BE

NOT AFRAID |

LOVE

IS STRONG AS

DEATH

MANY WATERS CANNOT

QUENCH LOVE

NEITHER CAN THE

FLOODS DROWN

IT

|

[Isaiah

43.2]

[Matthew

14.27]

[Song

of Solomon 8.6-7, EBB Sonnet XXVIII]

A

A  A

A

While sculpting his dead

wife's tomb in Fiesole, Holman

Hunt painted this portrait

of a Tuscan girl plaiting straw and

this pencilled self-portrait of his sorrow,

a

'Grief Observed'.

_

_

Then journeyed to the Holy

Land and painted the Scapegoat by the shores of the Dead

Sea.

Holman Hunt's versions of

the 'Light of the World' are in St Paul's Cathedral and at

Keble College, Oxford.

Meanwhile, the 'English'

Cemetery became the final resting place of other of her

friends, Walter Savage Landor,5

_

_

1864.

The second tomb has his wife Julia on

top of their

son's

tomb, her back turned to her husband's, as far

from

him as she can get. She was the daughter of a

Swiss

bankrupt banker.

Isa Blagden,6

_

_

1873

whose view from her house at

Bellosguardo Elizabeth would purloin for Aurora Leigh.

Robert Lytton, who attended

Elizabeth's funeral along with Isa, was the son of Edward

Bulwer-Lytton, had published poetry under the name of 'Owen

Meredith' and became Viceroy of India. Elizabeth had hoped

Lytton would marry Isa, for she had saved his life one

summer in Bagni di Lucca, when the Brownings were also

there, but Isa's mixed blood, part Jewish, part East Indian

(she and Theodosia being Hawthorne's models for Miriam in The

Marble Faun), prevented the match. They both wrote

works about their romance, Lytton's Lucile, a kind of Aurora Leigh, in verse,

Isa's Agnes Tremorne

in prose.

Likewise Fanny and Theodosia

Trollope,7 who as Theodosia Garrow had been

Elizabeth's girlhood friend at Torquay in Devon, are buried

here.

_

_

1865

Tom,

Fanny, Bice, and Theodosia Trollope

in

Villino Trollope, Piazza dell'Indipendenza

Elizabeth, Isa and Theodosia

all shared in an exotic colonial background, not being

completely English.

As for Pen, our Swiss Evangelical Reformed Church

records also reveal much about him. Moisé Droin had baptised

him in the Swiss Church at the Brownings' special request, for

they were Dissenters, and we have these baptismal records.

Elizabeth writes to Arabella telling her she goes with Pen

weekly to the Swiss Church in Florence. She allows Wilson to

take Pen into Catholic churches and witness the Mass there.

She herself describes several times in Aurora Leigh with great

observation the liturgy of the Santissima Annunziata. She

doesn't set foot in the English Church of the Holy Trinity. It

was following Elizabeth's death that Robert would wrench his

remaining family into the Church of England, with the burial

service for her, even to paying the tax to the English church,

in having Pen groomed to be a proper English gentleman,

desiring that he study Classics at Balliol under Benjamin

Jowett, and being himself buried with full honours in the

'Poets' Corner' of Westminster Abbey. The child, 'Pen', Robert

Wiedeman Browning, of Casa Guidi Windows, became the

man who as Robert Barrett Browning would drop the 'Wiedemann'

part of his name derived from his father's dead mother,

keeping instead his own dead mother's name of 'Barrett',

alongside his father's 'Browning'. When Pen married, he and

his wife even constructed a chapel in the Palazzo Rezzonico to

the memory of Elizabeth placing there the same words as on

Casa Guidi's plaque but in letters of gold. We recall that Pen

studied art in France, including sculpture under Rodin. Then

painted his father with The Old Yellow Book in his

hands in the portrait given to Balliol College, a portrait

Leighton, Millais, and Alma Tadema praised most highly (George

Barrett, 326), Leighton having supported Pen for membership in

the Athenaeum Club (316),

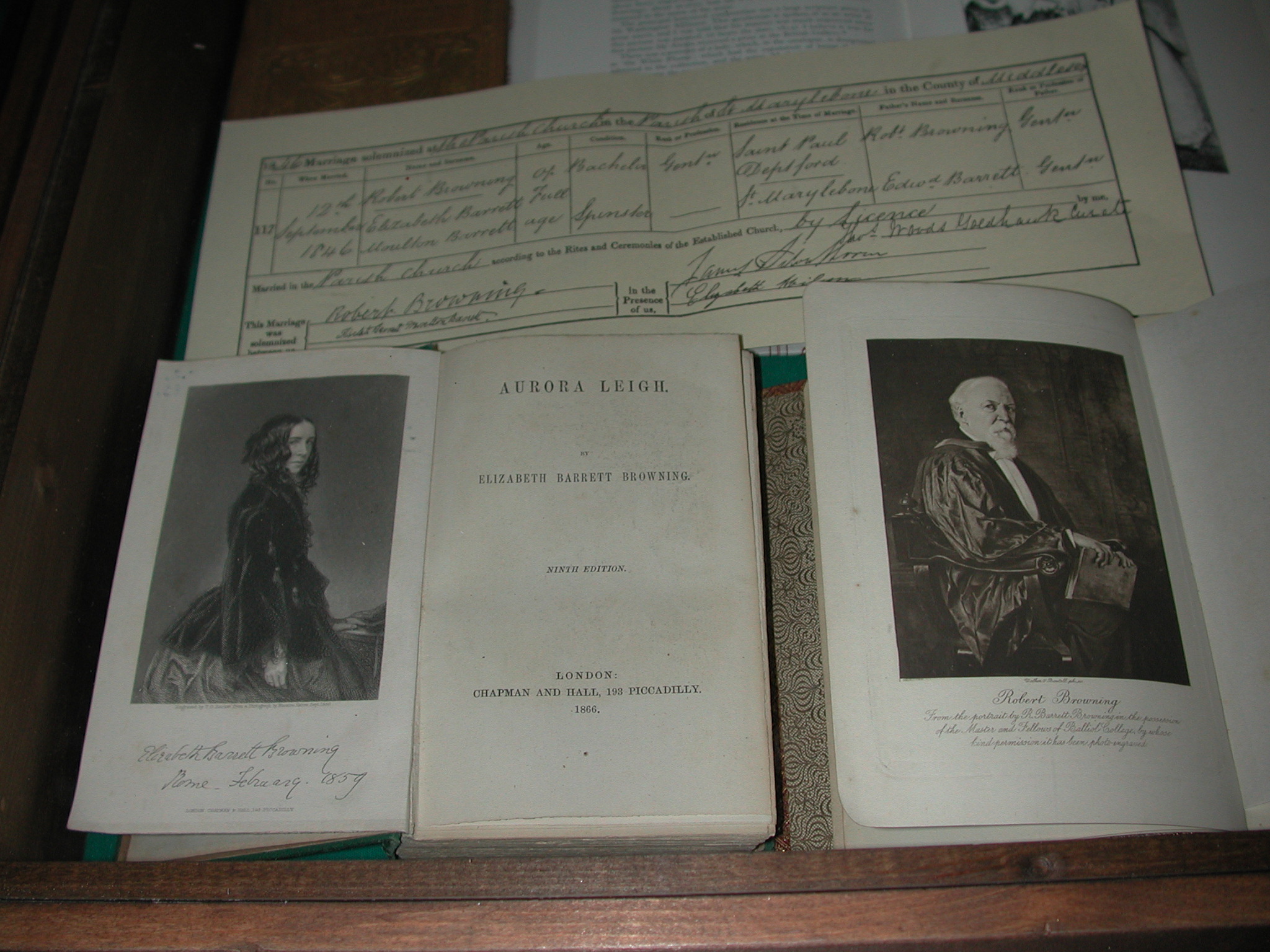

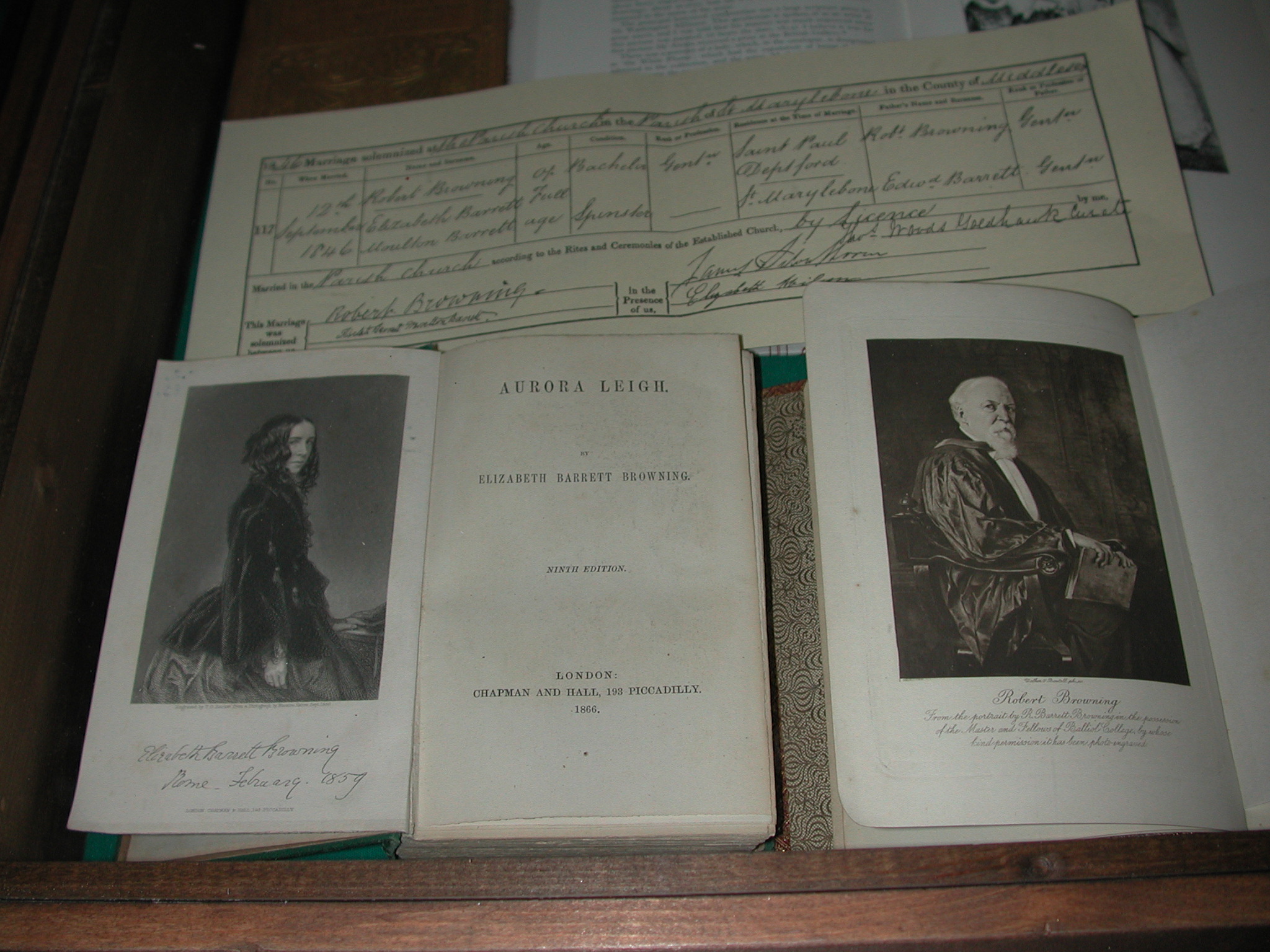

Robert Browning. From the

portrait by R. Barrett Browning in the possession of the

Master and Fellows of Balliol College, by whose kind

permission it has been photo-engraved

The Savonarola Chair is that seen in the Mignaty

painting, now in the Armstrong Browning Library.

and he sculpted a fine bust of his illegitimate

daughter Ginevra, Elizabeth's granddaughter, as Pompilia.

Robert Barrett Browning,

'Pompilia', Armstrong Browning Library

Model, Ginevra

For he returned to Italy, and gathered up all his

family's faithful retainers and looked after them, especially

the beloved and damaged Elizabeth Wilson who sought to protect

his mother from harm.

Thus, in the

English Cemetery are many love stories, the most famous and

iconic that of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning, but

also those of Fanny Waugh and William Holman Hunt, Isa

Blagden and Robert Bulwer-Lytton, Theodosia Garrow and

Thomas Adolphus Trollope, Elizabeth and Hiram Powers, and

even stories of stormy marriages, among them those of Julia

Thuillier and Walter Savage Landor, Margherita Albani and

Giorgio Mignaty, and, I suspect, that, again, of Elizabeth

Barrett and Robert Browning reflected in his poem about

Porphyria and her lover, written before his marriage, in his

poem about Lucrezia del Fede and Andrea del Sarto, written

during their marriage, and in his poem about Pompilia

Comparini and Guido Franceschini, written following

Elizabeth's death, and in her epic/romance about Romney and

Aurora Leigh.

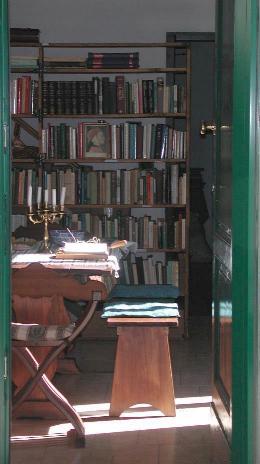

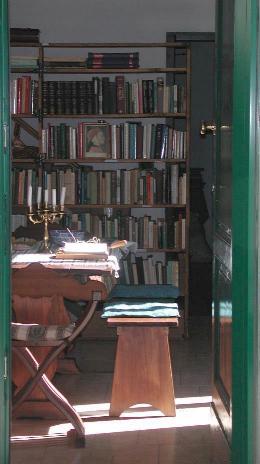

In our library within this Cemetery we continue to seek

books needed for this research, among them Robert Browning's

Letters, Dearest Isa,

and Henry James, William

Wetmore Story and His Friends, that this may be a

place where all may come to study these Anglo-Florentines.

You may visit us in person or on the Web, google-earthing

for Piazzale Donatello, Firenze, Toscana, Italy, where you

may see this Gate House with its library to the right, and

Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb by Lord Leighton to the

centre left of the laurel-hedged path, between the two x's,

amidst the cypresses and cedar:

x/Gordigiani's

Studio

x

Found

today

among the Cemetery's documents are the following letters. The

first H.P. Moulton-Barrett wrote from East Hill House, Ottery St

Mary, Devon, 16 September 1930 to the Swiss-owned 'English'

Cemetery because he had heard her tomb 'was in a bad state'. He

offers to pay for the restoration. The Swiss Cemeteries'

Inspector, writing to him as 'Illustrissimo Signore', after

saying no one has ever paid anything towards the maintainance

and the years have considerably damaged it, informs him the cost

will be the stupendous 1500 lire, plus another 100 lire for the

guard. Two years later, the Inspector, not having had any reply,

writes to him again. Then, 10 July 1933, the Inspector writes to

Florence's Mayor because Moulton-Barrett has now written twice

about the state of the tomb, giving copies of these two letters

(we only have one, the other must have been blistering), and

asks the Mayor to come and see it. 27 July 1933, the Mayor sends

a message that the Comune will pay for the restoration of the

tomb and the Ufficio Belle Arti has the responsibility of

carrying this out. 26 August 1933, the Capo Ufficio Belle Arti

writes to the Cemeteries' Inspector saying the Mayor is paying

and the work will commence the beginning of the next week,

listing the skilled workers who will undertake it. It is

very moving, seeing these letters, rusting from paper clips,

yellowed, frayed, and witnessing this caring down the centuries

by Florence and by the Moulton-Barretts for her. They were still

helping with this restoration. And the Comune was still

participating, though no longer paying.

Let me end with the beginning of Elizabeth's Tricentennial

and what the Comune of Florence has wrought in tribute to

her genius.

Notes

1^*§ CAROLINE

(BENNETT)

NAPIER/ ENGLAND/

Napier/ Carolina/ / Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 5 Settembre/ 1836/ /

141/ GL 23773/4 N° 50: died at Villa Capponi, Rev Knapp; Baptism

children: GL23773 N° 16 Arthur Lennox b 24/12/33 bp 31/03/34 Rev

Hutton, G23773 N° 52; Richard Henry b 11/03/36 bp 28/05/36 Rev

Hutchinson, father Henry Edward capt RN mother Caroline/ Maquay Diaries: 6 Sep 1836; 21 September/ DNB

entry: 'Napier, Henry Edward 1789-1853, historian, born on 5

March 1789, was son of Colonel George Napier [q.v.], younger

brother of Sir Charles James Napier [q.v.], conqueror of

Scinde, of Sir George Thomas Napier [q.v.], governor of the

Cape of Good Hope, and of Sir William Francis Patrick Napier

[q.v.], historian and general. . . . His chief claim to notice

is that he was the author of ‘Florentine History from the

earliest Authentic Records to the Accession of Ferdinand the

Third, Grandduke of Tuscany,’ six vols., 1846-7, a work

showing much independence of judgment and vivacity of style,

but marred by prolixity. He was elected a fellow of the Royal

Society on 18 May 1820, and died at 62 Cadogan Place, London,

on 13 Oct. 1853. He married on 17 Nov. 1823 Caroline Bennet, a

natural daughter of Charles Lennox, third duke of Richmond;

she died at Florence on 5 Sept. 1836, leaving three

children'./ Hare,

Horner cite

Napier's Florentine History/ NDNB entry for

husband, Henry Edward Napier/ CAROLINE

NAPIER/ WIFE OF/ CAPTAIN/ HENRY EDWARD NAPIER, R.N./ BORN/ 9TH

AUGUST 1806/ DIED/ 5TH SEPTEMBER 1836/ IF I HAD THOUGHT THOU

COULDST HAVE DIED/ I MIGHT NOT WEEP FOR THEE/ BUT I FORGOT

WHEN BY THY SIDE/ THAT THOU COULDST MORTAL BE/ IT NEVER

THROUGH MY MIND HAD PAST/ THAT TIME WOULD E'ER BE OER/ AND I

ON THEE SHOULD LOOK MY LAST/ AND THOU SHOULDST SMILE NO MORE/

AND STILL UPON THAT FACE I LOOK/ AND THINK TWILL SMILE AGAIN/

AND STILL THE THOUGHT I CANNOT BROOK/ THAT I MUST LOOK IN

VAIN/ BUT WHEN I SPEAK THOU DOST NOT SAY/ WHAT THOU NEER

LEFTST UNSAID/ AND NOW I FEEL AS WELL I MAY/ SWEET CAROLINE

THOU'RT DEAD/ IF THOU WOULDST STAY EEN AS THOU ART/ ALL COLD

AND ALL SERENE/ I STILL MIGHT PRESS THY SILENT HEART/ AND

WHERE THY SMILES HAVE BEEN/ WHERE EER THY CHILL BLEAK CORSE I

HAD/ THOU DIDST STILL SEEM MY OWN/ BUT HERE I LAID THEE IN THY

GRAVE/ AND I AM NOW ALONE/ I DO NOT THINK WHERE ER THOU ART/

THOU HAST FORGOTTEN ME/ AND I PERHAPS MAY SOOTHE THIS HEART/

ON THINKING TOO OF THEE/ YET THERE WAS ROUND THEE SUCH A DAWN/

OF LIGHT NEER SEEN BEFORE/ AS FANCY NEVER COULD HAVE DRAWN/

AND NEVER CAN RESTORE/-/ A10T(135)/ See Bennett, for mother's tomb beside hers,

also the Kellet tombs of three descendants from Captain Robert

John Napier Kellett (1797-1853).

2 Give tomb inscriptions for Mignaty

children. Thomas Adolphus

Trollope, What I Remember, II.311, notes that Signora

Mignaty was the niece of Sir Frederick Adam, who himself had

married a Greek lady. 'I remember her aunt, a very beautiful

woman. The niece, Signora Margherita Albani as she was when I

first knew her at eighteen years old in Rome, inherited so

much of the beauty of her race that the Roman artists were

constantly imploring her to sit for them. She has made herself

known in the literary world by several works, especially by a

recent book on Correggio, his life and works, published in

French'7

3*°§ HIRAM POWERS/

AMERICA / Powers/ Franco [later corrected to

Hiram]/ Stefano/ America/ Firenze/ 27 Giugno/ 1873/ Anni 69/

1220/ F. Hiram Powers, America, Sculpteur, fils de

Etienne Powers/ HIRAM POWERS/ DIED JUNE 27TH 1873/ AGED 68/

E15D °=Niccolò, Alessio

Michahelles, descendants

Contemporary Photograph in the Diary of Susan Horner, 1861-1862.

see the entries for Horner and Zileri for members of this

family.

4*§ +/FANNY WAUGH HUNT/ ENGLAND/ (Wough)[Waugh]/ Holman

Hunt]/ Fanny/ / Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 20 Dicembre/ 1866/ Anni

33/ 959/ Fanny Wough Hunt, l'Angleterre/ [Freeman,

227-230]/ NDNB entry for Holman Hunt/ [Written

in Medallions on Coffin with Dove and Olive/Pelican in its

Piety, Lilies, at each End, Floating on Water, on the Waves of

the Sea]

WHEN

THOU

PASSEST

THRO

THE

WATERS

I

WILL BE WITH THEE

AND

THRO THE FLOODS

THEY

SHALL NOT

OVERFLOW

THEE

|

IT IS

I

BE

NOT AFRAID |

LOVE

IS STRONG AS

DEATH

MANY WATERS CANNOT

QUENCH LOVE

NEITHER CAN THE

FLOODS DROWN

IT

|

[Isaiah

43.2]

[Matthew

14.27]

[Song of

Solomon 8.6-7]

//[on tomb and repeated on plaque at base] FANNY/ THE

WIFE OF/ W. HOLMAN HUNT/ DIED IN FLORENCE DEC 20 1866/ IN THE

FIRST YEAR OF HER MARRIAGE/ Holman

Hunt, Sculptor/ E13I

5*§°WALTER

SAVAGE

LANDOR/ ENGLAND/

Landor/ Gualtiero Savage/ / Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 17 Settembre/

1864/ Anni 90/ 879/ Walter Savage Landor, l'Angleterre/

GL23777/1 N° 348 Burial 19/09, Rev Pendleton/ Freeman,

223/ Thomas Adolphus Trollope, What I Remember,

II.244-262, notes Landor and the Garrows knew each other well

from Devon days, gives Landor's letter about Kate Field's

Atlantic Monthly article mentions the Alinari photograph

of himself/ NDNB entry/ IN

MEMORY OF/ WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR/ BORN 30th OF JANUARY 1775/

DIED 17th OF SEPTEMBER 1864/ AND THOU HIS FLORENCE TO THY

TRUST/ RECEIVE AND KEEP/ KEEP SAFE HIS DEDICATED DUST/ HIS

SACRED SLEEP/ SO SHALL THY LOVERS COME FROM FAR/ MIX WITH THY

NAME/ MORNING STAR WITH EVENING STAR/ HIS FAULTLESS FAME/ A.G.

SWINBURNE/ F9E °=Gen. Pier

Lamberto Negroni Bentivoglio

6*§

ISABELLA BLAGDEN/ INGHILTERRA?/

+/135. Blagden/ Isabella/ Tommaso/ Svizzera/ Firenze/ 20

Gennaio/ 1873/ Anni 55/ 1194/ Isabelle Blagden, l'Angleterre,

fille de Thomas/ GL23777/1 N°447, Burial

28/01, Rev. Tottenham/ Thomas Adolphus Trollope, What I

Remember, II.173-175 / NDNB entry/ Henderson/ ISABELLA

[Cross on Flower Garland] BLAGDEN/ BORN . . . DIED

. . . 1873/ THY WILL BE DONE . . ./

F11C

7*§ THEODOSIA (GARROW) TROLLOPE/ ENGLAND/ Trolloape [Trollope]/

Teodosia/ [Joseph Garrow]/ Inghilterra/ Firenze/ 12 Aprile/

1865/ Anni 46/ 904/+/ Theodosia Trollope, l'Angleterre/GL23777/1 N° 357 Burial 15/04 Age 46 Rev

Pendleton; Marriage GL23774 N° 71+170/6 N° 71 03/04/48 Thomas

Adolphus Trollope to Theodosia Garrow at HBM (Hamilton) bride

d of Joseph Garrow, Devon, Rev Robbins; Baptism of child

GL23775 N° 219/40, Beatrice Catherine Harriet 05/05/53, father

Thomas Adolphus Esq, mother Theodosia, Rev O'Neill/ Thomas

Adolphus Trollope, What I Remember, II.150-159,

166-168, & Chapter XVIII, who describes her as Florence's

new Corinne; pp. 171-173. on her childhood friendship with

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, both invalids to tuberculosis in

Torquay/ NDNB entries for Theodosia Trollope, James

Archibald Stuart-Wortley, whose grandson married first

Theodosia's daughter, Bice, then Millais' daughter, Caroline/

THEODOSIAE TROLLOPE/ T. ADOLFI TROLLOPE CONIUGIS/ QUOD

MORTALE FUIT/ HIC IACET/ OBITUM EIUS FLEVERUNT OMNES/ QUANTUM

AUTEM FERRI MERUIT/ VIR EUGUI SCRIPTORES/ SCIT SOLUS/ JOSEFE

GARROW ARMr FILIA/ APUD TORQEW IN AGRORUM DEVON ANGLORUM NATA/

FLORENTIAE NOMEN AGENS LUSTRUM/ AD PLURES DIVINAE . . ./

MENSES APRILES A.D. 1865/ F11E/ See Fisher, Garrow, Trollope, Shinner

Bibliography

Elizabeth

Barrett Browning. The Complete Works. Eds. Charlotte

Endymion Porter, Helen Archibald Clarke. 1900. Reprint, New

York: AMS Press, 1973.

George

Eliot. Romola. London: Smith Elder, 1862-1863.

Originally published in 14 parts in The Cornhill Magazine.

Nathaniel

Hawthorne. The Marble Faun, or the Romance of Montebeni.

1860. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1860.

Sophia

Peabody Hawthorne. Notes on England and Italy. New York:

Putnam, 1872.

Henry James.

William Wetmore Story and His

Friends, from Letters, Diaries, and Recollections.

Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1903. 2 vols.

Ernest

Jones. Hamlet and Oedipus. New York: W.W. Norton, 1949.

['There is a delicate point here which may appeal only to

psychanalysts. It is known that the occurrence of a dream within

a dream (when one dreams that one is dreaming) is always found

when analysed to refer to a theme which the person wishers 'were

only a dream', i.e. not true. I would suggest that a similar

meaning attaches to a 'play within a play', as in 'Hamlet'. So

Hamlet (as nephew) can kill the King in his imagination since it

is 'only a play' or 'only in play'. P. 101.]

The Letters of Elizabeth Barrett

Browning. Ed. Frederic G. Kenyon. New York: Macmillan,

1899.

The

Letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to Her Sister Arabella.

Ed. Scott Lewis. 2 vols. Waco: Wedgestone Press, 2002.

The Letters of

Robert Browning. Ed. Thurman

L. Hood. London: John Murray, 1933.

Jeannette

Marks. The Family of the Barrett: A Colonial Romance.

New York: Macmillian, 1938.

Geoffrey C.

Munn. Castellani and Giuliano: Revivalist Jewellers of the

19th Century. New York: Rizzoli, 1984. [Notes also,

figures 4-5, 34, that Fanny is portrayed by Holman Hunt with

such an Etruscan jewel.]

A New Spirit of the Age. Ed. Richard

Hengist Horne. London: Smith, Elder, 1844.

Mrs.

Sutherland Orr. Life and Letters of Robert Browning.

Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1891.

Gary

Schornhorst. 'Kate Field and the Brownings'. Browning Society Notes 31

(2006), 35-58.

Thomas Adolphus Trollope. What I Remember.

London: Richard Bentley, 1887.

Maisie Ward.

The Tragi-Comedy of Pen Browning, 1849-1912. New York:

Browning Institute, 1972.

Lilian

Whiting. A Study of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Boston:

Little, Brown, 1902.

Lilian

Whiting. Kate Field: A Record. Boston: Little, Brown,

1900.

Virginia

Woolf. 'Aurora Leigh'. Second Common Reader. London:

Hogarth Press, 1935.

Virginia

Woolf. Flush: A Biography. London: Hogarth Press, 1933.

_

Pen played

Cupid to a little girl's Psyche (Arabella, II.521), Rome

1861

_

FLORIN WEBSITE ©

JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO

ASSOCIATION, 1997-2007: FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH' CEMETERY ||

BIBLIOTECA E

BOTTEGA FIORETTA MAZZEI || ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING || FLORENCE

IN

SEPIA ||

BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI AND GEOFFREY CHAUCER || E-BOOKS || ANGLO-ITALIAN

STUDIES || CITY

AND

BOOK I,II, III, IV || NON-PROFIT

GUIDE TO COMMERCE IN FLORENCE || AUREO ANELLO,

CATALOGUE ||

LIBRARY

PAGES:

MEDIATHECA

FIORETTA MAZZEI || ITS ONLINE

CATALOGUE || HOW TO RUN A

LIBRARY || MANUSCRIPT

FACSIMILES || MANUSCRIPTS

|| MUSEUMS ||

FLORENTINE

LIBRARIES, MUSEUMS || HOW TO BUILD

CRADLES AND LIBRARIES || BOTTEGA || PUBLICATIONS

|| LIMITED

EDITIONS || LIBRERIA

EDITRICE FIORENTINA || SISMEL EDIZIONI

DEL GALLUZZO || FIERA DEL LIBRO

|| FLORENTINE

BINDING || CALLIGRAPHY

WORKSHOPS || BOOKBINDING

WORKSHOPS

LIBRARY

PAGES:

MEDIATHECA

FIORETTA MAZZEI || ITS ONLINE

CATALOGUE || HOW TO RUN A

LIBRARY || MANUSCRIPT

FACSIMILES || MANUSCRIPTS

|| MUSEUMS ||

FLORENTINE

LIBRARIES, MUSEUMS || HOW TO BUILD

CRADLES AND LIBRARIES || BOTTEGA || PUBLICATIONS

|| LIMITED

EDITIONS || LIBRERIA

EDITRICE FIORENTINA || SISMEL EDIZIONI

DEL GALLUZZO || FIERA DEL LIBRO

|| FLORENTINE

BINDING || CALLIGRAPHY

WORKSHOPS || BOOKBINDING

WORKSHOPS

y story begins

and ends in the Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery in

Florence. In Elizabeth's day and at her funeral, 1 July 1861,

this is how it looked, nestled by the wall and gate Arnolfo di

Cambio had built. Gathered about her coffin were Robert and

Pennini, widower and orphan, Isa Blagden, Robert Bulwer-Lytton,

Kate Field, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, the Powers, the Storys,

but no carriage was dispatched to bring Walter Savage Landor.

y story begins

and ends in the Swiss-owned so-called 'English' Cemetery in

Florence. In Elizabeth's day and at her funeral, 1 July 1861,

this is how it looked, nestled by the wall and gate Arnolfo di

Cambio had built. Gathered about her coffin were Robert and

Pennini, widower and orphan, Isa Blagden, Robert Bulwer-Lytton,

Kate Field, Thomas Adolphus Trollope, the Powers, the Storys,

but no carriage was dispatched to bring Walter Savage Landor.

__

__ __

__

A

A  A

A

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

_

LIBRARY

PAGES:

LIBRARY

PAGES: