FLORIN

WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA

BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024:

ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET

NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH' CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY ||

FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY

AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS I, II,

III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII

, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO

ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE ||

LINGUE/LANGUAGES:

ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA

New: Opere

Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence

APP TO GEORGE ELIOT'S ROMOLA

AND HER FLORENCE

Download and split screen with https://www.florin.ms/Romola.html

The oral reading of the novel is available on Librivox: https://librivox.org/romola-by-george-eliot/

but errs in titling the preface 'Prologue' and not Eliot's echoing

of Savonarola's 'Proemio'.

Map: 1 Dante House and Loggia dei

Cerchi; 2 Mercato

Vecchio and Corso dei Adimari to 3

Duomo and its Piazza San Giovanni; 4

Ponte Vecchio; 5 Oltrarno,

Via dei Bardi; 6 Borgo

Pinti and its Porta a' Pinti; 7

Palazzo del Popolo, della Signoria and its Piazza; 8 Badia fiorentina and Corso

degli Albizzi 9

Piazza Ognissanti; 10 San

Marco; 11 Santissima

Annunziata; 12 Rucellai

Gardens; 13 Via Valfonda; 14 Ponte Rubaconte and Piazza

de' Mozzi; 15 Santa Croce

and its Piazza; 16 Borgo

and Porta La Croce; 17

Porta San Gallo ->Trespiano; 18

Impruneta->San Gaggio->Florence; 19

San Stefano; 20 Oltrarno,

San Miniato; 21 Bargello; 22 Viareggio; 23 Oltrarno, Porta San Frediano;

24 Ponte alla Carraia; 25 Ponte Santa Trinità. You can

also explore these places using Google Earth.

Map of Florence, Augustus Hare, Florence

George Eliot

published her carefully-researched historical novel set in

Renaissance Florence, Romola, first in Cornhill

Magazine serially with Frederic

Lord Leighton's illustrations for it, his drawings now in

the Houghton Museum, Harvard University, which were executed as

mirror-reversed engravings by John Swain and others for being

printed, and next included in book form, London: Smith, Elder,

1863, a de luxe limited edition of a 1000 copies of the same being

printed in 1888. Guido Biagi,

next, in 1906, edited the novel from his perspective as a

scholarly Florentine librarian, London: Fisher Unwin, 1907,

filling two volumes of the text with photographs between almost

every three pages showing the buildings George Eliot had seen and

used, many of which no longer exist, being destroyed in the

Risorgimento and in World War II or which have been altered, as

well as authograph documents, etc. Both Leighton and Biagi had

intimate knowledge of Florence, Leighton having studied at the

Accademia di Belle Arti, Biagi being librarian of the

Magliabecchian and Laurentian libraries. All three were

celebrating and teaching Florence's former greatness, blending, as

had Dante Alighieri in the Commedia, fact with fiction,

history with romance, in order to share Florentine learning with

everyone, all three clearly understooding, also, the partnership

between art and literature. Frederic Leighton carried out similar

homage to the other great English woman writer of Florence,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, illustrating her "Musical Instrument"'s

figure of Pan, then designing her tomb in Florence's English Cemetery,

placing on its first harp the head of the god Pan from the

Giardino Torrigiani, at the same time that George Eliot was

writing Romola, while his sister, Mrs Sutherland Orr,

wrote Robert Browning's official biography. Everything in Florence

is 'intrecciato', intertwined, particularly the Anglo-Florentines

and their love of the city with their crafting in their art and

literature a 'golden ring twixt Italy and England'.

Guido Biagi's Introduction to the edition of Romola he

edited in 1907:

THE

MAKING OF THE ROMANCE

In this "historically illustrated" edition of the most classical

romance of modern English literature it will be interesting to

attempt an investigation, new, curious, and engrossing, of the

historical foundation upon which is based this work of art and

fiction, to try to discover the hidden scaffolding which supports

it, and see what materials have been employed in the building— to apply, in short,the Roentgen rays of

criticism to the fair form of "Romola" in order to behold the

historical skeleton divested of all clothing of romance or

embellishment of art and imagination.

Such an investigation could not be attempted without great

difficulty in the case of an Italian author, in whom certain

national ideas and historical knowledge had, through long habit of

study and surroundings, been so thoroughly absorbed as to become,

as it were, part of his flesh and blood. But when, on the

contrary, we have to do with a stranger in the land, who made but

a brief sojourn amidst the scenes he was about to describe, it

should not be difficult, amongst the records of things seen and

books read and studied, to trace the source of that inspiration

under the influence of which his work appeared to him first

vaguely and indistinctly, little by little assuming definite shape

and form. For in the unconscious working of our creative faculties

lies hidden the mechanism of dreams, which, arising from things

seen and remembered, sometimes soar to visions of serene beauty

peopled with graceful radiant fancies. But that reality, whence

the dream was born and took its flight, often appears to those who

seek it behind the golden clouds of the dream to be very mean and

bare; and yet, without that first impulse derived from the

reality, the fanciful creation would never have come into being,

just as without an inventive genius these germs of fact would have

remained inactive and wasted.How many there are who pass through

some lovely country, treading upon the poetry of the land as upon

stones, and who afterwards marvel that they should have been

there, yet have seen nothing. How many had read the chronicles of

Florence and studied the great drama of Savonarola without even

dreaming that against that historical background could arise, pure

and stately as an antique statue, the noble figure of Romola?

To Mary Ann Evans, better know as George Eliot, as to all elect

souls in whom is inborn the love of Italy, a journey through the

classic land of memories must have seemed like the realization of

a long-cherished dream, almost the fulfilment of a religious vow.

In the middle of the last century the present too easy means of

communication had not yet robbed that pilgrimage of all its

poetry, and travellers journeyed by post-chaise and diligence,

putting up in tiny hamlets and isolated villages, where they were

brought into far closer contact with men and things, and received

from them impressions far more vivid and exact than is possible

nowadays. Then the traveller could dawdle on the way as long as he

pleased and admire a fine view or building without feeling

compelled by the necessity of travel to hurry on in search of

fresh impressions: and a journey to Italy represented to a

superior and educated minds "the enlargement of our general life,

rather with hope of the new element it would bring to our culture,

than with the hope of immediate pleasure."

And it seemed to Miss Evans that this dream was about to be

realized, in order to "absorb some new life and gather fresh

ideas," just at the time when George Eliot, the famous but still

mysterious author of "Scenes of Clerical Life" and of "Adam Bede,"

had completed the last page of "The Mill on the Floss," dedicating

to her life-long companion, George Henry Lewes, that third

chef-d'oeuvre: "written in the sixth year of our life together."

in a calm, conscious, unprejudiced communion of the affection and

intellect. The author had brought to a mournful close the record

of her thoughtful girlhood "on the banks of the Floss," and now

spread her wings for flight to higher and more impersonal

conceptions. On the 21st of March, 1861, she wrote this sentence

in her diary: "We hope to start for Rome on Saturday, the 24th:

Magnificat anima mea!"

Mary Ann Evans had retained a very vivid impression of Italy. On

arrival at Genoa from Turin, which latter city they had reached by

way of the Monte Cenis, travelling partly in diligences and partly

in sleighs, she remembered having been there eleven years

previously, in June 1849; when she was in great grief after her

father's death and sought distraction in a short trip on the

continent in the company of her friends, the Brays. "I was here,"

she wrote in her diary, "eleven years ago, and the image that

visit had left in my mind was surprisingly faithful, though

fragmentary." The view of Genoa with "the masts of the abundant

shipping" was still the same, but not so was the mind of her who

gazed upon it.

From Genoa they went by sea to Leghorn, thence to Pisa; then by

way of Leghorn again, to Civitavecchia, where they took the train

to Rome, crossing the desolate Campagna "crowded with asphodels,

inhabited by buffaloes," with occasionally the sight of some

sombre hawk winging its flight across the plain. After Roma they

paid a brief and fatiguing visit to Naples and its surroundings,

Pozzuoli, Baja, Capo Miseno, Capodimonte, Poggio Reale, Pompei,

also to the Museum, and farther still, to Salerno, Paestum,

Amalfi, Cava, and Sorrento. Then, leaving this smiling land and

sky, they returned to Leghorn by sea, touching at Civitavecchia,

and finally the two pilgrims reached Florence, arriving there on

the 17th of May and remaining until the 1st of June.

That Florentine springtime, seen and felt in the communion of two

elect souls, whose exquisite culture rendered doubly keen the

delight of the enjoyment, those radiant days spent amidst the

marvels of art and the enchantment of nature clothed in all her

wealth of flower, whilst Italy and her people abandoned themselves

in hopeful confidence to all the enthusiasm aroused by their newly

acquired liberty, all this must have made upon the mind of the

author an everlasting impression of keen delight and indescribable

longing.

In Rome they had had "the very worst Spring that has been known

for the last twenty years," and that city, in which, at that

period, the stranger was struck chiefly by two things, the cobble

paving and the mud, had certainly not shown itself under its best

aspect. Moreover, the great metropolis with its immensity, its

historical buildings, its ruins of two worlds and two

civilizations, seems overwhelmingly fearful and solemn to those

who visit it for the first time, and neither unbends nor appeals

to the passing wanderer. In order to some degree to penetrate the

character and enter into the spirit of Rome, there must be visits

often renewed, lonely meditations on all the meaning of that great

name, frequent invokings of the past, long and thoughtful

contemplation of the city under all its varied aspects, in the

sunsets of its golden Autumn, in the sharp clearness of its Spring

skies, the torrid heat of Summer, and the calm freshness of its

starry nights. Florence, on the contrary, seems to speak directly

to the heart and mind of anyone who beholds her, on some fair

Spring morning, from the ethereal height of one of her verdant

hills. She has had but one civilization, one period of greatness,

one flower-time of art and poetry. Here was a brilliant Spring of

life and youth, through the lasting vigour of which the robust and

venerable trunks still flourish and from time to time burst forth

in blossom; it would almost seem that the great souls of her

"makers" still lived and breathed within those creations of stone

and marble which glisten in the sun, immortal witnesses t

centuries of thrilling history, to imperishable traditions of art

and life.

George Eliot felt immediately all the suggestive charm of the

Florentine landscape. "Florence looks inviting as one catches

sight from the railway of its cupolas and towers and its

embosoming hills, the greenest of hills, sprinkled everywhere with

white villas." They took rooms in the Pension Suisse, in Via

Tornabuoni, opposite the Palazzo Strozzi and the loggia of the

Palazzo Corsi, which, before its restoration, faced the Via della

Spada and served as the gaily-hued shop of a florist.

On that first evening of their stay in Florence the travellers

"took the most agreeable drive to be had round Florence, the drive

to Fiesole. It is in this view that the eye takes in the greatest

extent of great billowy hills, besprinkled with white houses

looking almost like flocks of sheep,—the great,

silent, uninhabited mountains lie chiefly behind,—the

plain of the Arno stretches far to the right. I think the view

from Fiesole the most beautiful of all; but that from San Miniato,

where we went the next evening, has an interest of another kind,

because here Florence lies much nearer below, and one can

distinguish the various buildings more completely. It is the same

with Bellosguardo in a still more marked degree. What a relief to

the eye and the thought, among the huddled roofs of a distant

town, to see the towers and cupolas rising in abundant variety as

they do at Florence! There is Brunelleschi's mighty dome, and

close by it, with its lovely colours not entirely absorbed by

distance, Giotto's incomparable Campanile, Beautiful as a jewel.

Farther on, to the right, is the majestic tower of the Palazzo

Vecchio, with the flag waving above it. Then the elegant Badia and

the Bargello close by; nearer to us the grand Campanile of Santo

Spirito, and that of Santa Croce; far away, on the left. the

cupola of San Lorenzo and the tower of Santa Maria Novella, and

scattered far and near other cupolas and campaniles of more

significant shape and history."

As appears from these pages of her diary, the topography of

Florence had firmly fixed itself in her artist's memory on her

first panoramic view of it, and the first germ of that wonderful

construction of the ancient city found in the Proem to "Romola"

was unconsciously evolved in the calm moonlight night when, on the

arm of her beloved guide, philosopher and friend, she stood on the

heights of Fiesole gazing down in fertile admiration at the city

of ivory and stone, and the silver streak of the Arno stretching

away westward down the luminous valley like some bright diaphanous

dream of the Spring.

The short stay of a fortnight was entirely devoted to exploring

the city, its churches, buildings, frescoes, galleries, and to

gathering in a rich treasure of impressions and memories. They

admired the "paradise gates" of the Baptistery, but the interior

seemed to them "almost awful, with its great dome covered with

gigantic early mosaic, the pale large-eyed Christ surrounded by

images of Paradise and Perdition." The interior of the 3 Cathedral, George Eliot says,

"is comparatively poor and bare, but it has one great beauty, its

coloured lanceolated windows." They never wearied of gazing at the

old fifteenth-century palaces, beginning with the Palazzo Strozzi,

built by Cronaca, perfect in its massiveness with its iron

cressets and rings, as if it have been built only last year." And

in the Palazzo Pitti they found "a wonderful union of cyclopean

massiveness with stately regularity." They recognized and

extolled, too, the magnificence of the Medici, now Riccardi

Palace. "Grander still, in another style, is the 7 Palazzo Vecchio with its

unique cortile where the pillars are embossed with

arabesque and floral tracery, making a contrast in elaborate

ornament with the large simplicity of the exterior building." The

Loggia of Orcagna appeared to her "disappointing at the first

glance from its sombre, dirty colour; but its beauty drew upon me

with longer contemplation. The pillars and groins are very

graceful and chaste in ornamentation." In the 21 Bargello, which was under

repair, she had "glimpses of a wonderful inner court, with

heraldic carvings and stone stairs and gallery."

These true and vivid impressions of the Florence of 1869, when

there still existed the fourth circle of walls, and the gutter ran

down the middle of the narrow streets, not yet overlaid with the

modern paving which has raised their level and thus deprived the

churches, palaces, and monuments of the steps which formed their

natural pedestals,--these records of the things she saw, which

were to remain as shining lights in the writer's memory, have

acquired for us a singular importance. The outlines and colours of

her historical background became indelibly fixed in her creative

mind; Florence began to be a part of her life, to occupy a

separate cell in her brain, to take possession of her thoughts

with a slow, constant, but unconscious penetration.

She considered the Florentine churches "hideous on the outside,"

like "piles of ribbed brickwork awaiting a coat of stone or

stucco," and with a daring but easy imagination she likened them

to "skinned animals." At Santa Maria Novella she admired the

façade by Leon Battista Alberti and the frescoes by Orcagna, which

she pronounced superior to those in the Campo Santo at Pisa. At

San Lorenzo the Medici Chapel seemed to her "ugly and heavy with

all the precious marble"; and strange to say, she added that "the

world-famous statues of Michael Angelo on the tombs in another

smaller chapel, the Notte, the Giorno and the Crepuscolo, remained

to us as affected and exaggerated in the original as in copies and

casts." The vigorous and symbolical art of Buonarroti found no

favour in the sight of one who preferred the simplicity of the

primitive masters and the fragile and delicate creations of the

preraphaelites.

It is easily understood, therefore, that the two friends preferred

the churches of Santa Croce and the Carmine, and that chief

amongst the great frescoes of Masaccio they placed the "Raising of

the Dead Youth," whilst of Giotto's they singled out the

"Challenge to pass through the Fire" in the series representing

the history of St Francis, which picture, on account of its

subject, must have made a special impression on the author.

But George Eliot had not yet seen 10

San Marco, a convent which in those days, before the unfortunate

suppression of the religious orders in 1865, still maintained its

customary existence as a Dominican monastery and had not yet been

reduced to a cold and empty museum. The cloisters, the

refectories, the halls, the chapels, the modest and spiritual

little cells were still inhabited by the heirs and successors of

the great Monk, and the glory halo of his martyrdom shed a light

of reverence and holiness over his humble followers and the places

where had been enacted the immemorable scenes of the great tragedy

of Savonarola's life, and over which his spirit seemed to hover,

invisible, but as ardent and living as before his body was reduced

to ashes. The clausura of the rules forbade women to enter

a part of the monastery, and this prohibition naturally increased

and strengthened George Eliot's desire to visit the building. "The

frescoes that I cared for most in all Florence were the few of Fra

Angelico's that a donna was allowed to see in the convent

of San Marco. In the Chapter House, now used as a guard-room, is a

large crucifixion, with the inimitable group of the fainting

Mother upheld by St John and the younger Mary and clasped around

by the kneeling Magdalene. The group of adoring sorrowing saints

on the right hand are admirable for earnest truthfulness of

representation. The Christ in this fresco is not good, but there

is a deeply impressive original crucified Christ outside in the

cloisters; St Dominic is clasping the cross and looking upward at

the agonized Saviour whose real, pale, calmly enduring face is

quite unlike any other Christ I have seen."

The artistic explorations continued, "That unique Laurentian

Library, designed by Michael Angel: the books ranged on desks in

front of seats, so that the appearance of the library resembles

that of a chapel with open pews of dark wood. The precious books

are all chained to the desks, and here we saw old manuscripts of

exquisite neatness, culminating in the Virgil of the fourth

century and the Pandects, said to have been recovered from

oblivion at Amalfi, but falsely so said, according to those who

are more learned than tradition,"

And herein we may see the hand of the Mentor, the learned friend

and companion, who corrected the mistakes of guidebooks and local

cicerones.

After the Laurentian Library came Or San Michele, the Ufizi, the

Palazzo Pitti, the Accademia, Galileo's Tower, and then after an

excursion to Siena, they visited the house of Buonarroti and the

Cenacolo of Foligno, which was then close to the Egyptian Museum.

They had chosen "the quietest hotel in Florence," in order to

avoid tourists and not be "in a perpetual noisy picnic . . .,

obliged to be civil, though with a strong inclination to be

sullen." Precisely at that time Tuscany was "in the highest

political spirits, and of course Victor Emmanuel, 'Il Re

Libratore,' stares at us at every turn here, with the most

loyal exaggeration of moustache and intelligent meaning. But we

are selfishly careless about dynasties just now, caring more for

the doings of Giotto and Brunelleschi than for those of Count

Cavour."

That year, for ever beloved and glorious in the memories of all

good Italians, was the year that saw Garibaldi's heroic deeds in

Sicily. And even the weather contributed its enchantment to that

springtime of the new kingdom of Italy. "We are particularly happy

in our weather, which is unvaringly fine without excessive heat."

And when, on the evening of the first of June, they left Florence

in the diligence, by the Bologna road, "travelling all night,

until eleven the next morning," to reach the city of towers, the

plan of the book was already determined and George Eliot was able

to confide it, as a secret, to Major Blackwood, "There has been a

crescendo of enjoyment in our travels; for Florence, from its

relation to the history of Modern Art, has roused a keener

interest in us even than Rome, and has stimulated us to entertain

rather an ambitious project, which I mean to be a secret from

everyone but you and Mr John Blackwood." And when an author thus

confesses to a publisher, the book is either already written or

must be written without fail.

From Bologna the travellers went to Ferrara, Padua, and Venice,

but the new impressions did not succeed in effacing their memories

of Florence, "Farewell, lovely Venice! and away to Verona, across

the green plains of Lombardy; which can hardly look tempting to an

eye still filled with the dreamy beauty it has left behind." From

Verona they went to Milan, to Como, and across the Splugen to

Zurich, and then, after brief halts at Berne and Geneva, they

returned home. "We found ourselves at home again, after three

months of delightful travel." On the first of July, George Eliot

reached her own house again, her thoughts still full of that

"unspeakably delightful journey, one of those journeys that seem

to divide one's life in two, by the new ideas they suggest and the

new veins of interest they open."

Meanwhile the hazy plan of the novel had assumed a definite form

and the secret had been completely revealed to Mr John Blackwood.

"I think I must tell you the secret, though I am distrusting my

power to make it grow into a published fact. When we were in

Florence I was rather fired with the idea of writing a historical

romance--scene, Florence; period, the close of the fifteenth

century, which was marked by Savonarola's career and martyrdom. Mr

Lewes has encouraged me to persevere in the project, saying that I

should probably do something in historical romance rather

different in character from what has been done before."

But in the meantime, before the echo of the great success obtained

by "The Mill on the Floss" had yet died away, she had another and

sudden inspiration which was in strong contrast with the great

Florentine idea. "It is a story of old-fashioned village life,

which has unfolded itself from the merest millet-seed of thought.

It came to me, first of all, quite suddenly, as a sort of

legendary tale, suggested by my recollection of having once, in

early childhood, seen a linen weaver with a bag on his back." And

on the 10th of March, 1861, "Silas Marner" was finished and the

author thought longingly of returning again to Florence in the

Spring, to gather fresh colouring for her cherished design.

On the 19th of April, they "set off on their second journey to

Florence, through France and by the Cornice Road. The weather was

delicious, a little rain, and they suffered neither from heat nor

from dust." The Cornice road was indeed delightful in that lovely

weather, and the view marvellous. From Toulon they had travelled

by the carrier, and after the necessary stoppages they reached

Florence on the 4th of May, going to lodge at the Albergo della

Vittoria on the Lungarno. "Dear Florence was lovelier than ever on

this second view, and ill-health was the only deduction from

perfect enjoyment."

The two friends were full of content; from London came excellent

notices of the success of "Silas Marner," and this fresh triumph

encouraged the author to begin a new novel. "I feel very full of

thankfulness for all the beautiful and great things that are given

me to know; and I feel, too, much younger and more hopeful, as if

a great deal of life and work were still before me" Their spirits

rose in the Florentine atmosphere. "I have had great satisfaction

in finding our impressions of admiration more than renewed on

returning to Florence: the things we cared about when we were here

before seem even more worthy than they did in our memories. We

have had delightful weather since the cold winds abated, and the

evening lights on the Arno, the bridges, and the quaint houses are

a treat that we think of beforehand."

On this second visit there was less wandering about, but more

meditation and more work. "We have been industriously foraging in

old streets and old books," she wrote. George Eliot was preparing

for her new venture, entering thoroughly into the life of her

subject, since, like all true artists, she could write of nothing

with which she was not, heart and mind and soul, in sympathy.

To be able to write she must also feel "that it was something,

however small, which wanted to be done in this world," and that

she was "just the organ for that small bit of work."

In this work of preparation and comparison George Henry Lewes

rendered the greatest possible assistance. He was "in continual

distraction by having to attend to my wants, going with me to the

Magliabecchian Library, and poking about everywhere on my behalf,"

she having "very little self-help of the pushing and inquiring

kind." They spent their time collecting materials and information

and admiring the surrounding country and the views. One evening

they mounted to the top of Giotto's Tower, a feat requiring much

exertion, but for the most part they contented themselves with

observing from the windows of their hotel "the various sunsets,

shielding crimson and golden lights under the dark bridges across

the Arno. All Florence turns out at eventide, but we avoided the

slow crowds on the Lungarno and took our way up all manner of

streets."

They arrived in Florence on the 4th of May, and they left on the

7th of June. "Thirty-four days of precious time spent there. Will

it be all in vain?" was the question George Eliot asked herself.

"Our morning hours were spent in looking at streets, buildings,

and pictures, in hunting up old books at shops or stalls, or in

reading at the Magliabecchian Library."

We have been fortunate enough to discover several documents of

singular curiosity and importance in connection with this long and

concluding sojourn in Florence, when the romance of Savonarola was

assuming its actual form in the mind and the creative imagination

of the author. We take a pleasure, in certain historical

researches, in imitating the methods, sometimes, perhaps, rather

suspicious methods, pursued by a clever detective when seeking the

material proofs of something that has happened; for it is the fate

of all human deeds, whether good or evil, always to leave some

trace behind them. It may happen, however, that through distance

of time and place these traces cannot be discovered, that either

carelessness or chance has destroyed them; but this is no reason

for denying that the fact ever occurred and that the traces of it

ever existed; we should have groped and searched diligently

whenever there was a chance, and something would surely have been

brought to light. It was this consideration, given the fact that

George Eliot and George Henry Lewes had really studied in the

Magliabecchian Library, that led me to think that some trace, some

record of these studies might still be found there. But during the

forty-four years from 1861 until the present time, the

Magliabecchian Library has passed through so many vicissitudes, so

many other collections of thousands of thousands of volumes have

been added to the original collection left by Antonio

Magliabecchi, there have been so many transformations and

rearrangements that any search of this description seemed wellnigh

hopeless. Only the old reading hall, which had been built in the

former Medicean Theatre,—the great

hall with its two huge windows, and the staircase at the end, and

the bust of Magliabecchi smiling grimly at the readers,—is

still exactly as it was when George Eliot and George Henry Lewes

sat down at their studies at one of those massive walnut tables.

There is the same peaceful stillness, barely disturbed even by the

greater number of readers: upon the shelves, with their ornamental

brass gratings, the same books await their turn to be read; nor is

there wanting some attendant who, in the May of 1861, might have

noticed the repeated visits of those two foreigners. An ancient

priest, in greasy skull-cap and snuffy cassock, then presided over

the books, keeping beside him as a guide the "Index librorum

prohibitorum." Another Cerberus, equally snuffy, kept guard

over the receipts for all books given out,—receipts which the students were obliged to sign

and file, and which were cancelled with the Library stamp when the

books were returned.

Knowing this old formality in the library economy of those days,

it occurred to me to search through the receipts of that year,

still preseerved at the top of a cupboard, in the office of the

archives, and from amongst those dusty bundles of many Italian

students, since become famous;—such

as Alessandro

d'Ancona, Enrico

Nencioni. and Ferdinando

Martini;—and names of many

obscure and humble persons who continued to frequent the Library

even in later years when I myself went there to study, before

entering on my career as a librarian. There were not many readers,—perhaps fifteen or twenty at the most; and

they went there rather to read through one book than to consult

several, often requesting the same volume for weeks together. From

George Eliot herself I found not a single receipt; but there were

a number signed G.H. Lewes, to whom she left all the trouble and

labour of those learned investigations in which she was not

accustomed.

Their first visit was paid on the 15th of May, and the first book

they sought was some illustrated work which would give them an

idea of the costumes of the period. They were given Ferrario's

"Costume Antico e Moderno," of which they examined the volumes

dealing with Italy. The author wished to obtain some knowledge of

the historical surroundings of her story, and to know in what

materials to dress her characters; and for this purpose a book

somewhat superficial and theatrical, as is that of Ferrario, could

be of service. On the following day they must have spent a longer

time in the Library, because their researches were more extended

and could not have been carried out without the assistance of one

of the Library attendants. They had the "Malmantile," by Lippi, a

comic poem which is a perfect mine of phrases, proverbs, and

quaint sayings, fully illustrated and explained by Canon A.M.

Biscioni; and it was doubtless in these instructive notes that

George Eliot found many of the jests and sayings which she was

pleased to insert in her novel in order that her characters might

speak the language of the period of which they wore the dress. But

the historical reconstruction and the scene could not be confined

only to the personages of the story,—the

background of the picture and the scenery must correspond with all

the rest; and hence in the "Firenze illustrata", by Leopoldo del

Miglione, and in "Firenze Antica e Moderna," by Rastreli, we find

them studying the aspect of the city at the end of the fifteenth

century, its topography and its various changes.

Besides printed books, they consulted manuscripts; and from the

"Priorista," by Luca Chiari, which bore the pressmark "Classe

XXVI, Cod 36, Palch, 1," they obtained the first idea of the

gorgeous magnificence with which they used to celebrate the Feast

of St John, with the homage of the various tributary towns, the

cars, the races, and the painted tapers of extraordinary size. the

illustrations from Del Migliore and from Chiari, which we have

reproduced, correspond fully with the descriptions of places and

ceremonies which she gives in her novel with an almost excessive

profusion of detail. But that was a mental necessity with her,

which she herself recognized. "It is the habit of my imagination

to strive after as full a vision of the medium in which a

character moves as of the character itself." It is not surprising,

therefore, that in order to satisfy this need, she eagerly read

any book whence she might derive precise ideas and knowledge of

the manners and customs of those days. On the 17th of May they

consulted the "Chronichette, Antiche della Città di Firenze," but

probably with little advantage. On the 18th, they examined four

other works; namely the "Diario," by Buonaccorsi, the "Istorie

Fiorentine" by Cavalcanti, the "Istorie Firoentine," by Nerli, and

the "Opere Volgari," by Poliziano. On the 19th, they studied

"Marietta dei Ricci," by Agostino Demollo, a historical romance

whose chief merit lies in the learned wanderings from the main

subject and in the notes on the families of old Florence appended

by Luigi Passerini. From these notes George Eliot undoubtedly

derived her first knowledge of the Bardi family, to whose

genealogical tree she added the ever-memorable figure of Romola.

[Guido Biagi (henceforth GB), I.xxxii. Among the

library slips not shown here is that for 'Poliziano Opere in

volgare 1503, 18 Maggio, GHLewes'. George Eliot was

consulting primary sources.]

During four days, from the 19th to the 24th, they

did not go to the Library. But on the 24th they returned to study

again "Marietta dei Ricci," and in vain to seek out in Litta's

book of Italian families, "Le Famiglie del Litta," the pedigree of

the Bardi. For now Romola, the Antigone of Bardo Bardi, was

already created, and George Eliot could take her to England and

weave around her the fabric of her romance, the costumes,

surroundings, language, and historical and genealogical background

for which she had studied in those few days at the Magliabecchain

Library, reserving the actual making of her romantic plot to be

done when she should reach her home.

After an excursion to Camaldoli and La Vernia, "which is perched

upon an abrupt rock rising sheer on the summit of a mountain,"

where they saw the grave and solemn Franciscans "turning out at

midnight (and when there is deep snow for their feet to plunge in)

and chanting their slow way up to the little chapel perched at a

lofty distance above their already lofty monastery," they returned

to London to the quiet house, 16 Blandford Square, where George

Eliot felt herself "in excellent health and longed to work

steadily and effectively."

She immediately began her studies and the varied reading required

for the elaboration of her book, her work relieved by walks with

George Lewes, during which "we talked of the Italian novel." But

the construction of the romance proved full of difficulties, often

overwhelming her with anxiety and discouragement. She felt she no

longer knew how to write, that she was no longer capable of

inventing a plot, and that she ought to give up her work. Her

diary is full of those alternating feelings, these continued

heights of joy and depths of despair. "This morning I conceived

the plot of my novel with new distinctness," she wrote on the 20th

of August. Then, on the 4th of October, "My mind still worried

about my plot, and without any confidence in my ability to do what

I want." But three days later, on the 7th of October, she wrote,

"Began the first chapter of my novel."

With this beginning, however, she was not satisfied and resumed

her reading, burying herself in the story of Nerli and of Nardi,

"so utterly dejected that in walking with George in the Park, I

almost resolved to give up my Italian novel." But on the 10th of

November a new prospect seemed to open before her, and she had a

"new sense of things to be done in my novel, and more brightness

in my thought . . . .This morning the Italian scenes returned upon

me with fresh attraction." She experienced renewed pleasure in her

Italian subject, and felt again captivated by its charm and

attractions. In order, then to bring it more vividly before her

mind, she went "to the British Museum reading-room, for the first

time, looking over costumes." On Sunday, the 6th of December,

whilst walking with Lewes "in the morning sunshine, I told him my

conception of my story, and he expressed great delight. Shall I

ever be able to carry out my ideas? Flashes of hope are succeeded

by the long intervals of dim distrust."

Meanwhile she continued her reading of erudite books. She had

finished the eight volumes of Lastri's "Osservatore Fiorentino,"

which she almost learned by heart, and which is the more immediate

source of all her information about old Florence, and had

commenced Book IX of Varchi's "Storie," "in which he gives an

accurate account of Florence." On the 12th of December she

finished writing out her plot,—of

which, however, she made several other drafts before really

beginning to write the book. What a solid and conscientious

foundation of study, how much hard reading, all in preparation for

a work of fiction and imagination! Of the books perused during

these long readings we find a long list in her diary, with the

titles more or less correct. Amongst these we naturally find the

work from which George Eliot obtained the greatest amount of

information about Savonarola and his times, namely, "La vita di G.

Savonarola," by Pasquale Villari, which had then only just been

published and was attracting the attention of the whole learned

world, and which came to be recognized as a masterpiece of

historical criticism. Of this book, for some unknown reason, we

find only a cursory mention in a note to the novel and in that

confused list of authors consulted by her, whilst in reality we

must attribute to this work a large share of the inspiration which

led her to write about Florence and the Dominican martyr who was

one of the two principal figures in the novel. Indeed, her use of

the most important scenes—that in

which Baldassare Calva makes his first appearance, when he meets

Tito Melema on the steps of the Cathedral—she

is indebted directly to Villari, the only writer who, on the

authority of the manuscript chronicles of Parenti and Cerratani

(to which George Eliot certainly had no access), describes the

fray which arose for the liberation of the Lunigiana prisoners, a

scene of which she made dramatic use in the second chapter of Book

II, entitled "The Prisoners." And who does not know the important

part of this liberation of the prisoners plays in the plot of

"Romola"? But amongst the sources, more or less direct, whence the

material of the novel was derived, like the "Novelle" of Sacchetti

(for the scene in the Mercato Vecchio and for the chapter entitled

"A Florentine Joke") and the "Veglie piacevoli" of Domenico Maria

Manni (for the character of the barber Nello, modelled upon that

of his great predecessor, the jolly poet Burchiello), none, in my

opinion, is equally important with that work which suggested to

the author such a fundamental point in her story.

In January, 1862, George Eliot wrote in her diary, "I began again

my novel of 'Romola,'" and set to work seriously,--a great

difficulty being the necessity of immediately gathering new and

correct partculars, which she sought to obtain on the 26th of

January, about Lorenzo de' Medici's death, about the possible

retardation of Easter, about Corpus Christi Day, about

Savonarola's preaching in the Lent of 1492. It is not easy to

imagine the care and industry with which she studied every detail,

every trifle of historical interest. She twice read through

Machiavelli's "Mandragora" and the "Calandra" by Bernardo Dovizi

for the sake of Florentine expressions, and she was never

satisfied with the result of her labours. On the 31st of

January she read to George Lewes "the proem and opening scene of

her novel, and he expressed great delight in them."

GB I.1

By the middle of February she had completed the first two

chapters, in addition to the admirable Proem, but the author was

still swayed between hope and fear. "I have been very ailing this

last week, and have worked under impeding discouragement. I have a

distrust in myself, in my work, in others' loving acceptance of

it, which robs my otherwise happy life of all joy. I ask myself,

without being able to answer, whether I have ever before felt so

chilled and oppressed. I have written now about sixty pages of my

romance. Will it ever be finished? Ever be worth anything?" this

uncertainty continued as the work of fiction gradually assumed

shape and form, through all the great difficulties which her

exquisite artistic taste pointed out and enabled her her

inspirations, as in her other romances, written on the impulse of

the moment at the dictating of her poetic and creative

self-control and selection were exercised in the presentation of

her imagination, forcing her to renewed efforts to rekindle it

each time she took up her work again after an interval of

historical or archeological research.

She had, meanwhile, accepted the offer of George Smith, the

publisher, and had agreed that "Romola" should appear in the

"Cornhill Magazine," and she received much encouragement and

advice from Anthony Trollope, a keen and wise judge on such

matters. The novel now made quicker progress, and by May the

second part was finished; by June the scene between Romola and her

brother in San Marco was written and she was about to commence

Part IV. In October she had also written the scene between Tito

and Romola and had completed Part VII, "having determined to end

at the point when Romola has left Florence." In November Part VIII

was ready, and in December Part IX. The novel had begun to appear

in the "Cornhill Magazine" in July, 1862, and from every side came

encouragement and praise.

"I have had a great deal of pretty encouragement from immense

big-wigs, some of them saying 'Romola' is the finest book they

ever read"; but the opinion of big-wigs has one sort of value and

she preferred "the fellow-feeling of a long-known friend." The

greater part of her work was now done, and the diary no longer

recorded uncertainty and indecision. In May, 1863, there was

wanting only this last part, and she had already "killed Tito with

great excitement," and on the 9th of June, ever memorable day, she

noted in her diary, "Put the last stroke to Romola—Ebenezer!" while on the first page of the

manuscript she wrote the following inscription:—

"TO THE HUSBAND WHOSE PERFECT LOVE WAS BEEN THE

BEST

SOURCE OF HER INSIGHT AND

STRENGTH

THIS MANUSCRIPT IS GIVEN BY HIS

DEVOTED

WIFE THE WRITER"

Romola was the fair fruit

of the union between erudition and poetry, the dream-child

conceived in that moonlit night in May when she stood upon the

ethereal heights of Fiesole, gazing down in the white and shadowy

city in the valley below. It was a long and laborious creation,

and for that reason greatly beloved.

"The writing of 'Romola' ploughed into her more than any of her

other books. She could put her finger on it as marking a

well-defined transition in her life. In her own words, 'I began it

as a young woman, I finished it an old woman.'"

Of this romance, whose poetical beginning we have seen and whose

historical and artistic facts we have traced to their source, we

should now like to quote some criticisms, concerning these

historical contents, pronounced by various unquestionable

authorities. Pasquale Villari, whose name is indissolubly linked

with that of Savonarola, says, in the second edition of his

monumental work, that amongst the books on this subject which have

appeared during the last few years, "The one which attracted the

most attention was a novel, "Romola," by George Eliot; but this

admirable work of art, by the great English author added no new

facts to the history, because, as was only natural, she accepted

unquestioningly the conclusions already arrived at." As he had

pronounced such a favourable judgment on the work of art, it may

be concluded that the illustrious Italian critic deemed it also

worthy of the highest praise for the reconstruction of historical

scenes, and that the author was quite justified in writing, "My

predominant feeling is, not that I have achieved anything, but—that great, great facts have struggled to

find a voice through me and have only been able to speak

brokenly."

But these very qualities of historical truth, of exact

reproduction of surroundings,—tested

by investigations whose results are embodied in the notes appended

to the text and by the examination of numerous iconographical

documents which give us a picture of Florence in the days of

Savonarola, as well as by a careful research amongst the books

whence the writer drew her inspiration,—these

qualities appear in the opinion of several recent critics, to be

one of the reasons why "Romola" with all its life-like vigour, its

vivid reality of representation, remains nevertheless, inferior to

the other purely imaginary romances with which George Eliot has

enriched English literature. A keen and genial Italian critic,

Gaetano Negri, who has written two volumes of essays on the works

of Marian Evans, attributes this weakness to the fact of its being

a historical romance and to the literary, artistic, and political

archaeology which impedes the freedom of movement and robs it of

the stamp of truth.

He bluntly accused George Henry Lewes of having allowed his

learning to exercise an evil influence on the genius of his

companion, and of not knowing how to prevent her from running now

and then into literary adventures which were for her both

dangerous and hurtful. Negri, a faithful admirer of Alessandro

Manzoni, wished that Lewes could have read the dissertation which

the author of "Promessi posi" wrote on the subject of the

historical novel, to prove that this is a form of literature not

to be cultivated because "the laborious adherence to historical

truth which is necessary in the historical novel, in order to form

the background for the probable, hampers the action and distracts

the attention from that which is really of importance; namely the

analysis of the human soul and its passions. This mixture of truth

and apparent truth is fatal to both; it robs the probable

of the stamp of truth, and it robs the real truth of the semblance

of probability; what is probable must also seem possible,

and what is truth must retain its impression of reality.

It is a fact that Manzoni, in spite of his theories, has given us

a masterpiece which contains not only an admirable picture of the

human soul. But it is certainly an instance of the exception

proving the rule, because the good result has been obtained

through the genius of the author, who has known how to overcome

the evils of the system."

We maintain, however, that this rule does not exist, for it has

been amply proved that no work of art can ever be created

according to fixed rules, even though these rules be drawn up by

men of genius. Manzoni's dissertation, and the arguments

syllogized by him after having given Italy such a work as

"Promessi Sposi," are one of the attacks of hypercriticism to

which even the cleverest men are occasionally liable. But these

sophisms did not prevent Sir Walter Scott from writing "The

Waverley Novels," nor Alexander Dumas from inventing "The Three

Musketeers," nor did they hinder Leo Tolstoi from writing "Peace

and War," or Henry Stenkwicz from the creation of "Quo Vadis." It

is not the fault of the historical romance if, according to some

opinions, the figure of Romola does not appear in sufficiently

strong relief against the historical background, whilst those of

Tito Melema and Baldassarre appear, even to a sceptical critic

like Gaetano Negri, more alive and more human. If there is a

defect in Romola, it is the fault of her nature, her inclinations,

her temperament; she is not Italian, she is an English girl, a

Puritan, to whom even the ardent mysticism of Savonarola is

repugnant and whose whole soul rises up in rebellion against him

when he declares, "The cause of my party is the cause of God's

Kingdom," to which she makes answer, "God's Kingdom is something

wider, else let me stand outside it with the beings that I love."

Romola has no Latin blood in her veins, none of that quick Italian

blood which boils up hot and furious at every offense, ready with

its scorn and its anger, but which, at the bidding of a watchful

mind, is ready also to be calm and to forgive. Through all Tito's

betrayals of her she never has one of those sudden outbursts and

blazes of passion which are natural in an offended woman: she

exhibits an unfailing self-control which chills us, a sad and

resigned coldness which does not belong to the Italian nature, and

was still less a characteristic of the women of the Renaissance,

even then, when Classicism and the finest Hellenism had educated

and civilized them. Romola is a Puritan, not a piagnona, a

follower of Savonarola; Romola is English, and she bears a curious

resemblance to George Eliot herself, or to what George Eliot's

daughter might have been had she had one.

But, having said this much, we have no right to make further

criticism or censure. Indeed, it may be urged, and with good

reason, that to judge Romola as one would judge any ordinary

character in any ordinary novel, as a creature who must of

necessity have flesh and blood and be subject to the same passions

as we ourselves, would be both unjust and inopportune and would

show a total disregard of those rules of criticism so clearly laid

down by Alessandro Manzoni when he advised a consideration of

three points before pronouncing judgment on a work of art; namely,

what was the intention of the author, was this intention good, and

has the author carried out his intention. We may, indeed, in all

sincerity ask ourselves whether, in creating Romola, George Eliot

actually intended to create a real personage.

Romola finds herself in conflict with two widely differing worlds,—the Humanism which fell into decay after

the pagan Carnival of Lorenzo dei Medici, after the splendour of

the golden time of Neo-Platonism, and the Asceticism which for a

brief period flourished again and proclaimed the rights of soul

and spirit as against the triumph of material things. She is

surrounded by ruin and dissolution; everything she loves most

either abandons her or falls into evil; she loses her family, her

love betrays her, her very faith itself has no comfort for her. In

this sad vanishing of all she values she can truly say with the

poet. "Ogni cosa al mondo è vana." Her father, her brother, and

her guardian are dead, the Prophet of her faith is but a handful

of ashes scattered to the winds, the two opposing factions of palleschi

and piagnosi are extinguished, and Romola is left with

Tessa and Monna Brigida, Lillo and Ninna, in the quiet house in

the Borgo Pinti, to dream out the memory of the tempestuous past

and to teach the children "that we can only have the highest

happiness by having wide thoguhts and much feeling for the rest of

the world as well as ourselves."

Romola stands out as a symbol, immaculate and strong, a symbol of

the woman who, after having hoped, suffered, and loved, after all

the fountains of her affections have been dried up by the fatal

touch of disillusionment, turns the stream of her unsatisfied

feelings towards those in misery and those who, all unconsciously

and involuntarily, have offended her; she is a figure sublime and

statuesque, and her name is Charity.

DR GUIDO BIAGI,

LAURENTIAN LIBRARY, FLORENCE,

JULY 1, 1906

The entire text of the novel with these illustrations supplied

by Frederic Lord Leighton and by Guido Biagi is at https://www.florin.ms/Romola.html. This page functions as a

hypertextual and archeological guide to that historical yet

deconstructing romance, as it were, articulating, x-raying, its

skeleton. As with Dante's

Commedia, of seven centuries ago, one can see that what

is real is the scholar's investigation of Florence of the end of

the fifteenth century, now six centuries ago, and its scholarly

investigator of a century and a half ago, from which the

novelist author articulates her fictional characters amidst real

personages, blending together both real and fictional worlds,

with a moral compass, in which the heroine Romola mirrors both

George Eliot and the Divine Mother, who endures the loss of all

scholarly and spiritual illusions with her brother's, father's,

godfather's, husband's and Savonarola's deaths, while its

villainous anti-hero's crime is that of maintaining in slavery

both his foster father and his two wives, a theme resonating

with the Victorian Florence of the Abolition of Slavery, the

Risorgimento, and the Liberation of Children and of Women.

George Eliot's Romola is her 'Distant Mirror' for

resolving the author's own Puritanical and Victorian moral

compass, renouncing a dead bookishness, those parchment scrolls

Romola's ascetic brother glimpses which are, in fact, this

novel's sources, her achieving self-worth in the face of false

patriarchy's mortmain. George Eliot does so by

juxtaposing the obedient daughter-wife to the two disobedient

sons in the text, the second of whom George Eliot, masked as

Baldassarre Calvo, kills off in the greatest excitement. She

just may be, using the lies of a novel, herself such a liar as

is Tito Melema, shrouding that self-truth with all the

historical trappings of extreme scholarly research into

verisimilitude—which turn into dead

parchment scrolls. We recall that she is herself part of a

pattern of adultery and bigamy, George Henry Lewes, her partner,

being legally married to Agnes Lewes, who, however was not

faithful to him, nor he to her, they having chosen to live an

open marriage. So many of her characters in this fictional novel

were real people complete with Wikipedia and Enciclopedia

Treccani entries and presented in fine portraits, now in

great museums. While the father and daughter are not really of

the Renaissance, but of the Victorian century, Bardo de' Bardi

modelled on the eccentric artist scholar, Seymour Kirkup,

discoverer of the portrait of Dante in the Bargello and of the

death mask, Romola modelled on herself. Indeed, George Eliot's

Romola looks in a mirror at herself in the text to test the

efficacy of her disguise, just as earlier Nello had Tito look at

his transformation. Iain McGilchrist, the neuroscientist, has

noted that first person narratives activate the brain more than

do novels with omniscient observers; in a sense, Romola

is a first person narrative, the reader being as if Romola, who

is as if a mirrroring of George Eliot's own Pilgrim's

Progress. For this novel, amidst all its distancing and

projection onto another, all its blending of real and virtual,

is a self-examination, as Nello the Barber called it, a nosce

teipsum mirror, a knowing of thyself. Two other characters

also note the change in their appearance: Baldassare sees

himself in the barber's hand mirror in Arezzo, and then in a

puddle of water, noting his aging; just as we find Monna

Brigida initially resists, then accepts, hers. The book is as if

George Eliot's own Bonfire of Vanities, her maturing. And it is

ours.

Florence

|

Dante

Alighieri, author

|

Dante

Alighieri, character

|

Commedia

|

Florence

|

George

Eliot, author

|

Romola

de' Bardi, character

|

Romola

|

Proem. As

introduction, George Eliot here has us survey the cityscape of

Florence at our feet through the eyes of a now dead Florentine in

1492. The "small, quick-eyed man"=Brunelleschi. Frati minori=

Franciscan friars. Palazzo Vecchio=Old Palace, People's Palace. 8 Badia=Abbey. Santa Croce (Holy

Cross)'s tower is Victorian, likewise the façades of 15 Santa Croce and of the 3 Duomo, Cathedral. 4 Ponte Vecchio=Old Bridge.

Oltrarno=the other side of the Arno River. Wax ex voto

images used to be hung in the 11

Santissima Annunziata (Most Holy Annunciation)'s atrium, such as

one can still see in Marian shrines as at Montenero and

Einsiedeln. All Florentines, until recently, because of tourism,

were baptised in Florence's Baptistery of San Giovanni, Easter

Saturday. marmi=marble. The Calimara was the guild for

Florentine merchants trading throughout the known world.

John Brett, Bellosguardo,

Tate

Frederic Leighton (henceforth FL), 1862-1863,1888, Proem,

Spirit of the Past at 20 San Miniato

1492 Tito Melema came to Florence as Lorenzo il Magnifico died. He

has been shipwrecked, is aided by the peddlar Bratti, and the

barber Nello, ought to ransom his foster father who is now

enslaved but instead uses the gems he has for that purpose for

himself. Falls for the contadina peasant Tessa, and for

the noble Romola in bigamy, is an anti-hero filled with anxiety

about his social-climbing as a scholar. Romola assists her blind

scholarly father, in place of her fanatic brother, Bernardino, now

Fra Luca, who dies telling her of the vision he has of her

marriage, as of parchment scrolls.

Chapter 1-The Shipwrecked Stranger

9 April 1492. Main characters in each chapter will be bolded.

Fictional characters, Tito Melema, Bratti Ferravecchi

(baratta=bargain), a peddlar, Monna Trecca, a greengrocer,

Goro, Nello, a barber, Ser Cioni, a lawyer,

Niccolo, a blacksmith. Historical persons mentioned are Antonio

Pucci, a poet, Lorenzo

de' Medici, the merchant prince who has just died in the

presence of the Dominican, Girolamo Savonarola, an event we come

to learn of in the cacaphony of market gossip. In a sense, Bratti

functions in the text like the author herself, bartering and

exchanging objects, introducing people to each other, setting

the plot in motion; likewise Niccolo, as blacksmith, forges its

weapons of crime.

'E vedesi chi perde con gran soffi,

E bestemmiar colla mano alla mascella,

E ricever e dar di molti ingoffi.'

Mercato=market,

castello=fortified village, marzolino=Tuscan sheep's

cheese, mi pare=seems to me, Frati serviti=Servites

of Mary, a Florentine Order, Quaresima=Lent when meat

could not be eaten, Marzocco is the Lion, emblem of

Florence, sculpted by Donatello. This first chapter is not easy to

read, presenting as it does a babble of voices in a crowded market

place, packed full of long-ago proverbs in a foreign tongue, much

like Bratti's peddler pack of wares, but bear with the author, for

the novel gets better.

FL, I

Guido Biagi (henceforth GB), I.76, 1907

FL (henceforth FL), 1862-1863, Bratti and Tito

GB, I.106

GB, I.98

Chapter 2-A Breakfast for Love

Fictional characters, Bratti, Tito, Tessa, Monna Ghita,

Nello. Historical persons mentioned, Demetrio Calcondila,

Bernardo Rucellai. Mercato Vecchio

obolus=Greek coin

Chapter 3-The Barber's Shop

Fictional character, Nello, Tito. Historic persons

mentioned, Lorenzo de' Medici, compared to Pericles of Athens,

Demetrio Calcondila, Michele Marullo, Bernardo Rucellai, Alamanno

Rinuccini, Pico della Mirandola, Giotto, Brunelleschi, Lorenzo

Ghiberi, Angelo Poliziano, Burchiello, Piero di Cosimo, Giovanni

Argiropulo, Bartolomeo Scala. Nello has Tito look at himself in a

Venetian mirror from Murano. Piazza San Giovanni.

'"Ingenium velox,

audacia perdita, sermo

Promptus, et Isaeo torrentior."

contadina=country woman

Frederic Leighton

(henceforth FL), 1862-1863,1888, Spirit

of the Past at 20 San

Miniato

GB, I.134

FL, Tito and Nello. The sculpture in the window is

of the stele or herm of the god Pan in the

Torrigiani Gardens which Leighton also placed on the first, Greek,

harp he placed on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb in Florence's

English Cemetery.

FL, Tito and Nello. The sculpture in the window is

of the stele or herm of the god Pan in the

Torrigiani Gardens which Leighton also placed on the first, Greek,

harp he placed on Elizabeth Barrett Browning's tomb in Florence's

English Cemetery.

Chapter 4-First Impressions

Tito, Nello, Domenico Cennini, printer, Bernardo Cennini's

son, Piero di Cosimo, mentioned, Francesco Filelfo, Angelo

Poliziano, Pietro Cennini, Domenico's brother, Pico della

Mirandola, Leonardo da Vinci. Here George Eliot is also speaking

of the impressions in printing of her book and its engravings.

That Piero di Cosimo sees Tito as Sinon, the betrayer though guile

of Troy (Timeo Danaos, ut dona ferentis/Beware the Greeks

bearing gifts, in this case of the Trojan Horse), from Virgil's Aeneid,

is prophetic of Tito's treachery.

The printer

Benardo Cennini's son, Domenico

Self-portrait,

Piero di Cosimo

Chapter 5- The Blind Scholars and his Daughter

Fictional characters: Maso, the servant, Bardo

de' Bardi, his daughter, Romola, Nello, Tito.

Historical persons mentioned, Agnolo Poliziano, Nonnus, Hadrian,

Apollonius Rhodius, Callimachs, Lucan, Silius Italicus, Petrarch,

Manuelo Crisolora, Filfelfo, Argiropulo, Panhormita, Poggio,

Thomas of Sarzana, Marsilio Ficino, Nicolo Niccoli, Cassandra

Fedele, Demetrio Calcondila, Plautus, Quintilian, Boccaccio, Aldus

Manuzio, printer, Pontanus, Merula, Epictetus, Horace, Zeno,

Epicurus

"Libri medullitus delectant, colloquuntur,

consulunt, et viva quadam nobis atque arguta familiaritate

junguntur." '

"Optimam foeminam nullam

esse, alia licet alia pejor sit."

"duabus sellis sedere"

"Sunt qui non habeant, est qui non

curat habere."

The Palazzo de' Bardi, via de' Bardi. Bardo dei Bardi,

is modelled by George Eliot from the Victorian

eccentric deaf scholar, Seymour

Kirkup, who lived in via dei Bardi, and who had

discovered Dante's portrait where Vasari said it was,

in the Magdalen Chapel of the Bargello.

The Palace was obliterated in World War II.

BG, I.182

BG, I.176

FL, Bardo and Romola, his daughter/Seymour Kirkup

Chapter 6-Dawning Hopes

Bardo, Romola, Maso, Nello, Tito. Historical person, Bernardo

del Nero, others mentioned, Manuelo Crisolora, Luigi Pulci,

Aurispa, Guarino, Ciriaco, Cristofero Buondelmonte, Ambrogio

Traversari, Demetrio Calcondila, Aristotle, St Philip, Pausanias,

Pliny, Margites, Domenico Cennini, Alessandra Scala, Bartolommeo

Scala, Camillo Leonardi, Lorenzo de' Medici, Piero de' Medici

There is an echo here of Tito telling of his background to that

narrated by Othello which enchants Desdemona in Shakespeare's

play.

"Perdonimi s'io fallo:

chi m'ascolta

Intenda il mio volgar col suo latino."

'Con viso che tocendo dicea, Taci.'

FL, VI

GB, I.210, Bernardo del Nero

Chapter 7-A Learned Squabble

Fictional character, Tito. Historical persons, Bartolommeo

Scala, mentioned, Agnolo Poliziano, Marsilio Ficino,

Cristofero Landino, Villa Gherardesca, Porta a' Pinti,

home to Bartolomeo Scala.

GB, I.232, Bartolomeo della Scala

GB, I.214, Villa Gherardesca, Borgo

Pinti

GB, I.228, Villa Gherardesca, Borgo Pinti, now Four Seasons

Hotel

.jpg)

GB, I.154, Agnolo Politian, Laurentian Library, who would be poisoned by the

Mediceans for his support of Savonarola

Marsilio

Ficino, who would be poisoned by the Mediceans for his

support of Savonarola

Marsilio

Ficino, Cristofero Landino, Agnolo Politian, Demetrio

Calcondila

Chapter 8-A Face in the Crowd

Fictional Characters, Tito, Nello, Fra Luca,

Tessa, mentioned Maestro Vaiano. Historical

Persons, Piero di Cosimo, Pietro Cennini,

Cronaca, Francesco Cei, Bernardo Del Nero,

mentioned Queen Theodolinda, Cecca, Girolamo Savonarola.

Piazza San Giovanni

"Da quel

giorno in qua ch'amor m'accese

Per lei son fatto e gentile e cortese."'

Frati Predicatori=Dominicans,

Giostra=tournament, Zecca=mint

GB, I.296

GB, II.6

Cassone Adimari

GB, I.244

Palio

GB, I.248 Tribute of the Prisoners

George Eliot consulted this manuscript

.jpg)

GB,

I.272 Florentine

Nobles

GB, I. 276 Sienese Nobles

.jpg)

GB, I.264

Montopoli

GB, I.268 Candles

GB, I.256 Cart of teh Zecca,

the

Mint

GB, I.260 Montecarlo Cart

Chapter 9-A Man's Ransom

Fictional Characters, Tito, mentioned,

Tessa, Nello, Baldassarre Calvo. Historical

persons, Domenico

Cennini pays

for the last

jewel, a

"man's

ransom", mentioned,

Demetrio Calcondila, Poliziano, Bernardo

Rucellai .

Chapter 10- Under the Plane Tree

Fictional characters, Tito had been

handed his florins from Cennini?, Tessa,

Maestro Vaiano, Fra Luca. Histoical

person mentioned, Lorenzo de' Medici. Scene

remniscent of Samson and Deliliah.

San Martino, Badia, Porta rossa, Ognissanti,

Porta del Prato, Peretola, via de' Bardi

FL, Under the Plane-Tree

FL, A Recognition. This is misplaced in the

1888 edition.

Chapter 11-Tito's Dilemma

Fictional characters, Tito, Fra Luca,

Romola, Bardo, mentioned, Baldassarre.

Via de' Bardi, San Marco.

Leighton's

view for the initial W is of the archway by

the Hospital of the Innocents in the

Santissima Annunziata Square.

Leighton's

view for the initial W is of the archway by

the Hospital of the Innocents in the

Santissima Annunziata Square.

Chapter 12-The Prize is Nearly Grasped

Fictional characters, Tito, Maso, Bardo,

Romola, Monna Brigida, mentioned,

Dino=Bernardino->Fra Luca.

Historical persons mentioned, Calderino,

Poliziano, Thucydides, Lorenzo Valla, Pope

Nicholas V, Thomas of Sarzana, Alibizzi,

Accaiuoli, Francesco

Valori, Bernardo del

Nero, Niccolò

Machiavelli, Franco

Sacchetti, Bernardo del

Nero, Bartolommeo Scala,

Alessandra Scala,

Michele Marullo.

Piagnoni=

followers of Girolamo Savonarola, named after

San Marco's bell. Good Men of St

Martin/Buonuomini di San Martino, Befana=cross

old lady wtih broom looking for Christ Child

at Epiphany

Good Men of St Martin=Buonuomini di San

Martino who carry out charity.

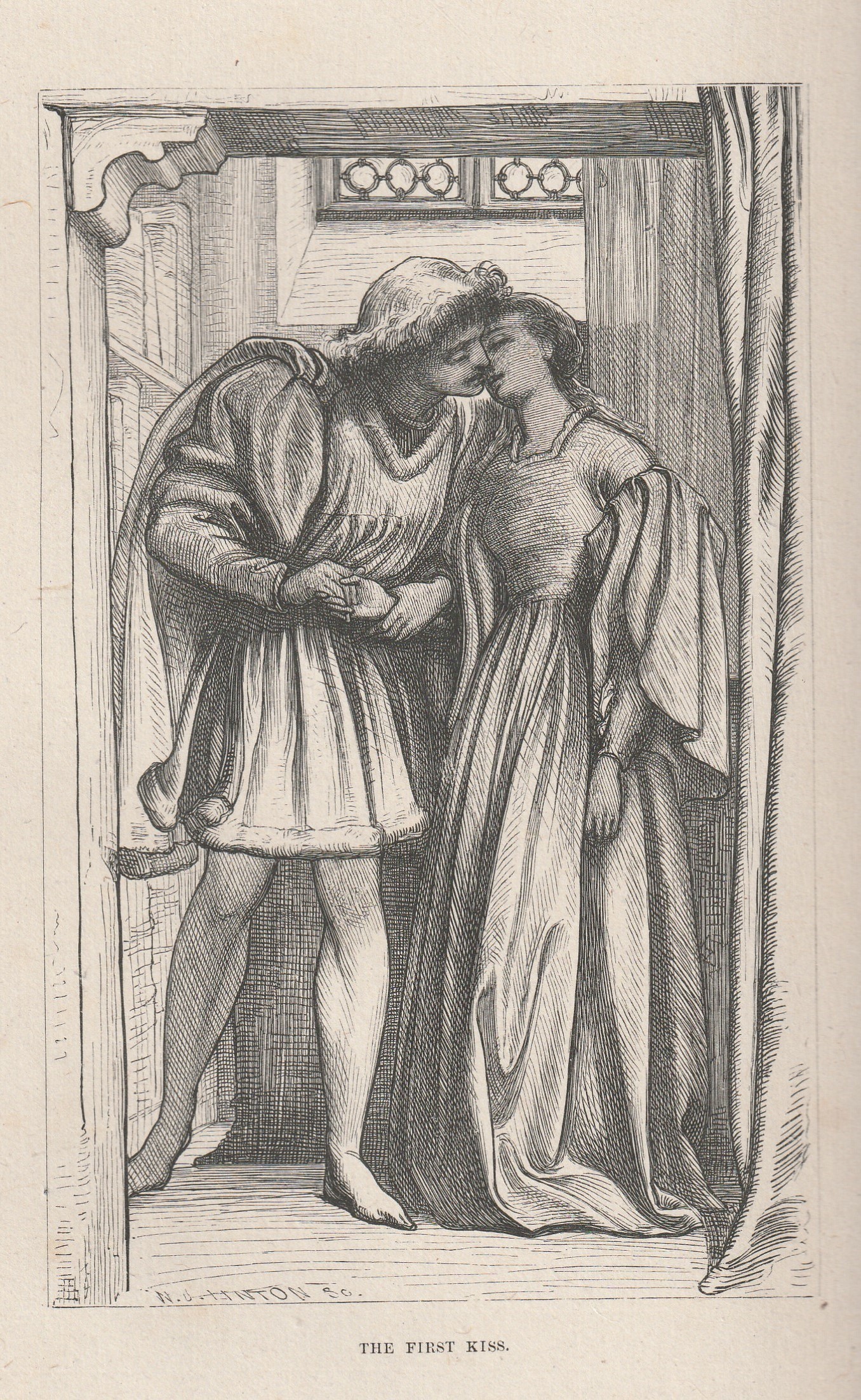

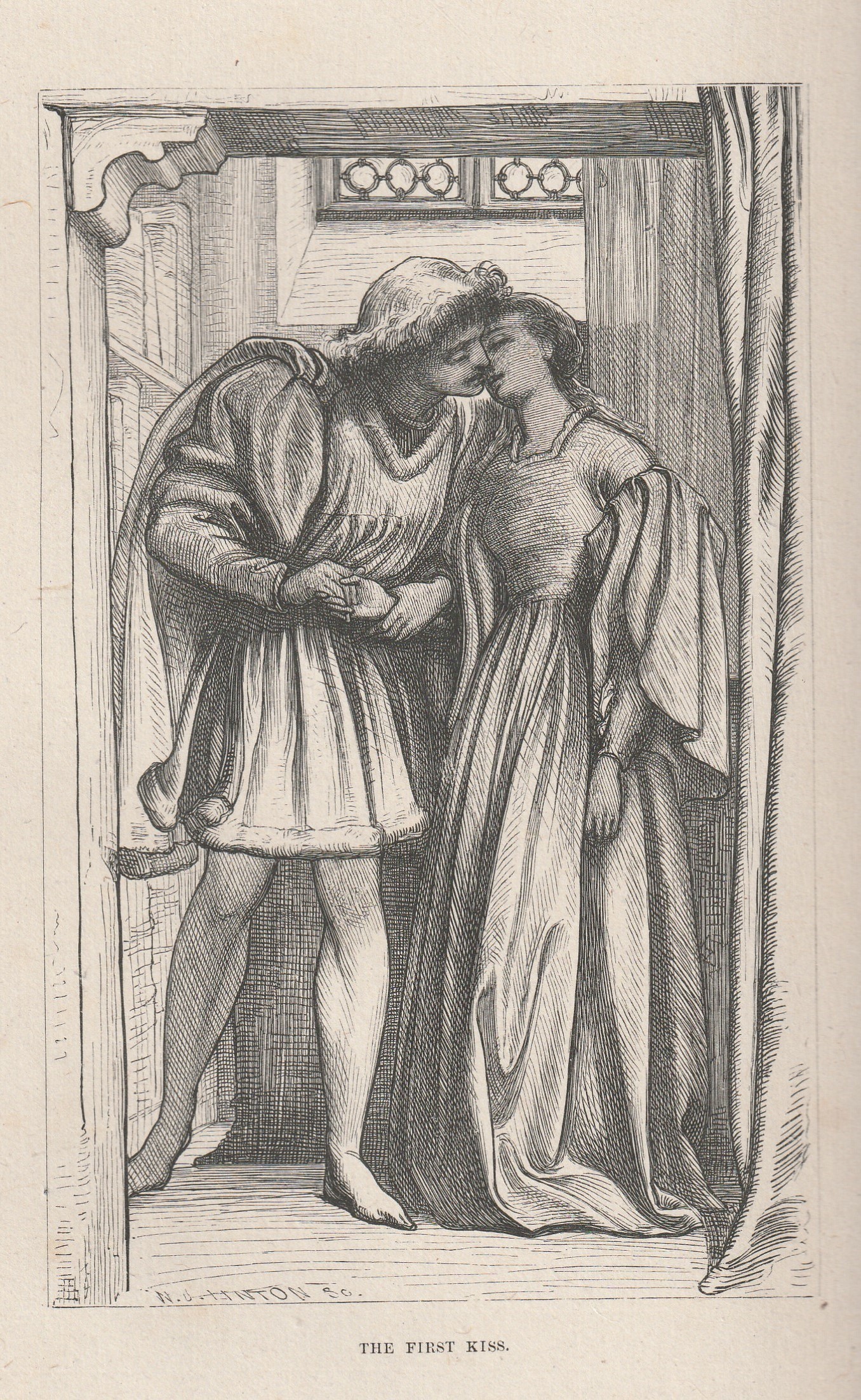

FL, The First Kiss

Chapter 13-The Shadow of Nemesis

7 September 1492 Fictional characters, Tito, Nello, Romola,

Monna Brigida, Bernardino/Fra Luca. Historic persons

mentioned, Giovanni de' Medici, Bernardo Dovizi, Piero Dovizi,

Piero de' Medici, Angelo Poliziano, Pietro Crinito, Dante

Alighieri, Francesco Cei, Cristofero Landino, Bernardo del Nero,

Cronaca.

'Quant' e bella giovinezza

Che si fugge tuttavia!

Chi vuol esser lieto sia,

Di doman non c'e certezza.

'Fierucola,

country market, Piazza Santissima Anunziata, San Marco,

Chapter 14-The

Peasants' Fair

My friend, Giannozzo Pucci, the descendant of the historical

Giannozzo Pucci in this romance, re-started the Fierucola in the

Piazza Santissima Annunziata, encouraging the contadini to

sell their produce and their wares.

Fictional characters, Tito, Bratti, Tessa, Maestro Vaiano

andate con Dio= Go with God

berlinghozzi=lemon doughnuts eaten in Lent

FL, The Peasants' Fair

Chapter 15-The Dying Message

Ficitional characters, Romola, Monna Brigida, Fra

Luca/Bernardino, Vaiano and his monkey. Historic person,

Girolamo Savonarola. San Marco

FL, The Dying

Message. Leighton has sketched the Fra Angelico fresco as

background. George Eliot had written:

"The frescoes that I cared

for most in all Florence were the few of Fra Angelico's that a donna

was allowed to see in the convent of San Marco. In the Chapter

House, now used as a guard-room, is a large crucifixion, with

the inimitable group of the fainting Mother upheld by St John

and the younger Mary and clasped around by the kneeling

Magdalene. The group of adoring sorrowing saints on the right

hand are admirable for earnest truthfulness of representation.

The Christ in this fresco is not good, but there is a deeply

impressive original crucified Christ outside in the cloisters;

St Dominic is clasping the cross and looking upward at the

agonized Saviour whose real, pale, calmly enduring face is quite

unlike any other Christ I have seen." Fra Luca, in

reality, was the Della Robbia brother who became a Dominican under

Savonarola. So many artists and scholars came under his influence,

among them Botticelli, Marsilio Ficino, and Agnolo Poliziano.

Chapter 16-A Florentine Joke

Fictional characters, Tito, Bratti, Nello, Niccolo

the blacksmith, Maestro Tacco, Maso, mentioned,

Fra Luca, Monna Ghita. Historical persons, Niccolò

Machiavelli, Cronaca, Piero di Cosimo, Francesco

Cei, Domenico Cennini, mentioned, Bernardo Rucellai,

Piero de' Medici, Domenico Cennini, Pagolantonio Soderini, Tommaso

Soderini, Fiametta Strozzi,Savonarola, Pico della Mirandola,

Angelo Poliziano, Marsilio Ficino, Pope Alexander VI, Luigi Pulci,

Antonio Benevieni, Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna, Saint Stephen,

Saints Cosmas and Damian, the Medici family's patrons, Cecco d'Ascoli.

Maestro Tacco is tricked into doctoring Maestro Vaiano's monkey,

bundled in fasces as if a baby.

"non oratorem, sed

aratorem."

Piazza San Giovanni, Corso degli Adimai ->via dei Bardi.

Niccolò

Machiavelli

Bernardo Rucellai

Piero de' Medici?

Chapter 17-Under the Loggia

Romola, Tito. Romola tells Tito of Fra Luca's dying.

Historical persons mentioned, Alamanno Rinucini, Bernardo del

Nero. Bardi Palace.

Chapter 18-The Portrait

Fictional characters, Tito, mentioned, Baldassarre,

Nello. Historical person, Piero di Cosimo, mentioned,

Ovid.

Bacchus and Ariadne. Oedipus and Antigone at Colonos. Via Valfonda

Piero di Cosimo, Andromeda and Perseus

Chapter 19-The Old Man's Hope

Fictional characters, Bardo, Romola, mentioned, Tito.

Historic person, Bernardo del Nero, Cardinal Giovanni

de' Medici, Piero de' Medici. The Library.

Chapter 20-The Day of the Bethrothal

Fictional characters, Tito, Tessa, Romola, Monna

Brigida, Bardo. Historic persons, Bernardo Dovizi,

Bernardo del Nero, Bartolommeo Scala, mentioned

Michelangelo Buonarotti, Piero di Cosimo, Leonardo Bruni.

Tabernacle of Piero di Cosimo. Spozalizia at Santa Croce, during Carnival.

Por Santa Maria, Porta

Rubaconte, Palazzo Bardi, Santa Croce.

Bernardo Dovizi as Cardinal of Bibbiena, Raphael

Chapter 21-Florence expects a Guest

17 November 1494.

Fictional character mentioned, Tito. Historical persons, Charles

VIII, Savonarola, mentioned, Lorenzo de' Medici, Ludovico

Sforza, Leonardo da Vinci, King Ferdinand, Prince Alfonso of

Naples, Pope Alexander Borgia, Piero de' Medici.

Charles VIII of France arrives by way of the Porta San Frediano,

the Medici already driven out of Florence. Tito's foster father

Baldassare Calvo refusing to beg. From Duomo to Palazzo Vecchio.

Girolamo Savonarola

Chapter 22-The Prisoners

Ficitional characters, Ser Cioni, Goro, Oddo, Tito,

Lollo, Baldassarre Calvo, mentioned Guccio.

Historical persons, mentioned, Piero de' Medici, Lorenzo

Tornabuoni, Piero di Cosimo, Lunigiana prisoners.

Piazza San Giovanni.

FL, The Escaped Prisoner

Chapter 23-After-Thoughts