FLORIN WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI, &

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE

SILENCE:

FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE

IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII

, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA

'FIORETTA

MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE

|| UMILTA

WEBSITE

|| LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA

New: Opere

Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence

Harpers

New Monthly Magazine, 84 (May, 1892), 832-855.With

thanks to Aureo Anello member, Charles Gould, Portland, Oregon.

ROBERT AND ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING

ANNIE THACKERAY RITCHIE

I

The sons and daughters of men and women eminent

in their generation are from circumstances fortunate in their

opportunities. From childhood they know their parents' friends

and contemporaries, the remarkable men and women who are the

makers of the age, quite naturally and without excitement. At

the same time this famility may perhaps detract in some degree

from the undeniable glamour of the Unknown; and, indeed, it is

not till much later in life that the time comes to appreciate. B

or C or D is a great man; we know it because our fathers have

told us; but the moment when we feel it for ourselves comes suddenly and

mysteriously. My own experience certainly is this. The friends

existed first, then, long afterwards, they became to me the

notabilities, the interesting people as well, and these two

impressions were oddly combined in my mind.

Such men are even now

upon the earth,

Serene amid the half-formed

creatures round.

Paracelsus

When the writer was a child living in Paris, she used to look

with a certain mingled terror and fascination at various pages

of grim heads drawn in black and red chalk, something in the

manner of Fuseli. Masks and faces were depicted, crowding

together with malevolent or agonized or terrific expressions.

There were the suggestions of a hundred weird stories on the

pages which we gazed at with creeping alarm. These pictures were

all drawn by a kind and most gentle neighbor of ours, whom we

often met and visited, and of whom we were not in the very least

afraid. His name was Mr Robert Browning. He was the father of

the poet, and he lived with his daughter in calm and pleasant

retreat in those Champs Elysées to which so many people used to

come at that time, seeking well-earned repose from their labors

by crossing the Channel instead of the Styx. I don't know

whether Mr and Miss Browning always lived in Paris; they are

certainly among the people I can longest recall there. But one

day I found myself listening with some interest to a

conversation which had been going on for some time between my

grandparents and Miss Browning - a long matter-of-fact talk

about houses, travellers, furnished apartments, sunshine, south

aspects, etc., etc., and on asking who were the travellers

coming to inhabit the apartments, I was told that our Mr

Browning had a son who lived abroad, and who was expected

shortly with his wife from Italy and that the rooms were to be

engaged for them, and I was also told that they were very gifted

and celebrated people; and I further remember that very

afternoon being taken over various houses and lodgings by my

grandmother. Mrs Browning was an invalid, my grandmother told

me, who could not possibly live without light and warmth. So

that by the time the travellers had really arrived, and were

definitively installed, we were all greatly excited and

interested in their whereabouts, and well convinced that

wherever else the sun might or might not fall, it must shine

upon them. In this homely fashion the shell of the future - the

four walls of a friendship - began to exist before the friends

themselves walked into it. We were taken to call very soon after

they arrived. Mr Browning was not there, but Mrs Browning

received us in a low room with Napoleonic chairs and tables, and

a wood fire burning on the hearth.

I don't think any girl who had once experienced it could fail to

respond to Mrs Browning's motherly advance. There was something

more than kindness in it; there was an implied interest,

equality, and understanding which is very difficult to describe

and impossible to forget.*/* Notwithstanding an incidental allusion in Mrs Orr's

life of Browning, I can only adhere to my own vivid impression

of the relations between Mrs Browning and my father./

This generous humility of nature was also to the last one

special attribute of Robert Browning himself, translated by him

into cheerful and vigorous good-will and utter absence of

affectation. But, indeed, one form of greatness is the gift of

reaching the reality in all things, instead of keeping to the

formalities and the affectations of life. The free-and-easiness

of the small is a very different thing from this. It may be as

false in its way as formality itself, if it is founded on

conditions which do not and can never exist.

To the writer's own particular taste there never will be any

more delightful person than the simple-minded woman of the world

who has seen enough to know what it is all worth, who is sure

enough of her own position to take it for granted, who is

interested in the person she is talking to, and unconscious of

anything but a wish to give kindness and attention. This is the

impression Mrs Browning made upon me from the first moment I

ever saw her to the last. Alas! the moments were not so very

many when we were together. Perhaps all the more vivid is the

impression of this peaceful home, of the fireside where the logs

are burning while this lady of that kind hearth is established

in her sofa corner, with her little boy curled up by her side,

the door opening and shutting meanwhile to the quick step of the

master of the house, to the life of the world without as it came

to find her in her quiet nook. The hours seemed to my sister and

me warmer, more full of interest and peace, in her sitting-room

than elsewhere. Whether at Florence, at Rome, at Paris, or in

London, once more, she seemed to carry her own atmosphere

always, something serious, motherly, absolutely artless, and yet

impassioned, noble, and sincere. I can recall the slight figure

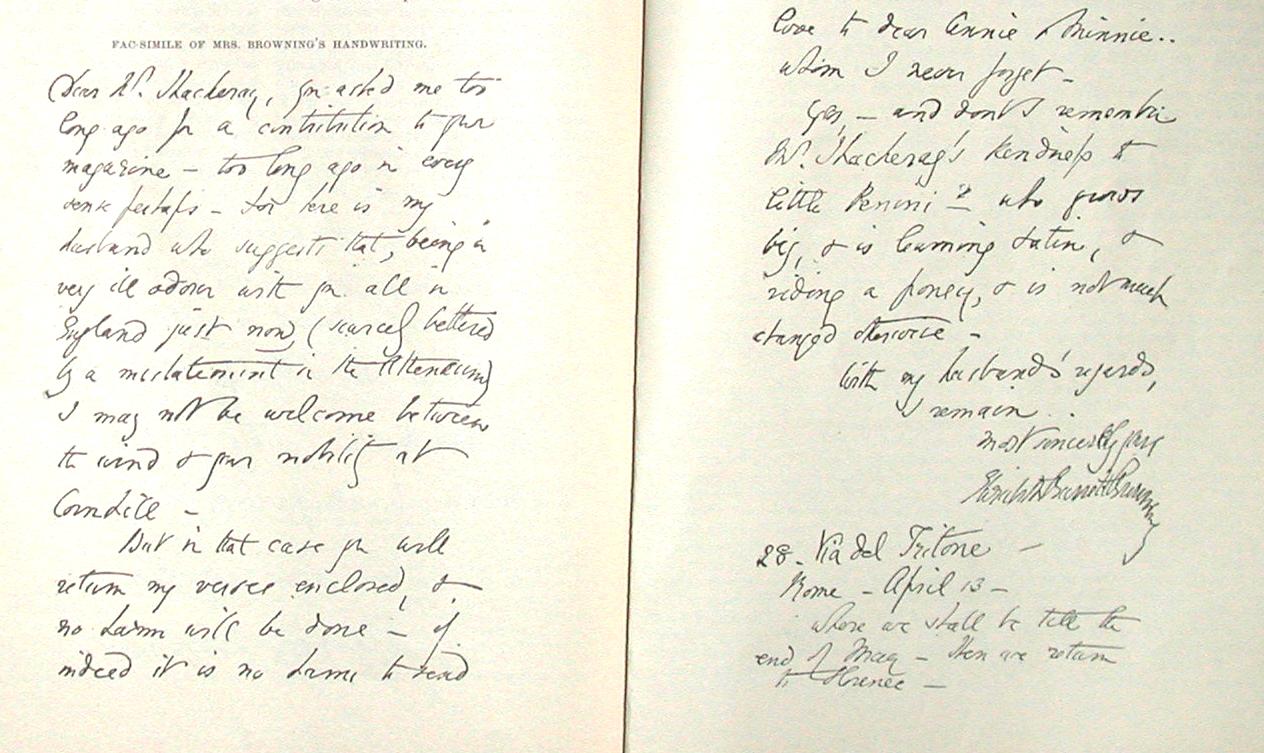

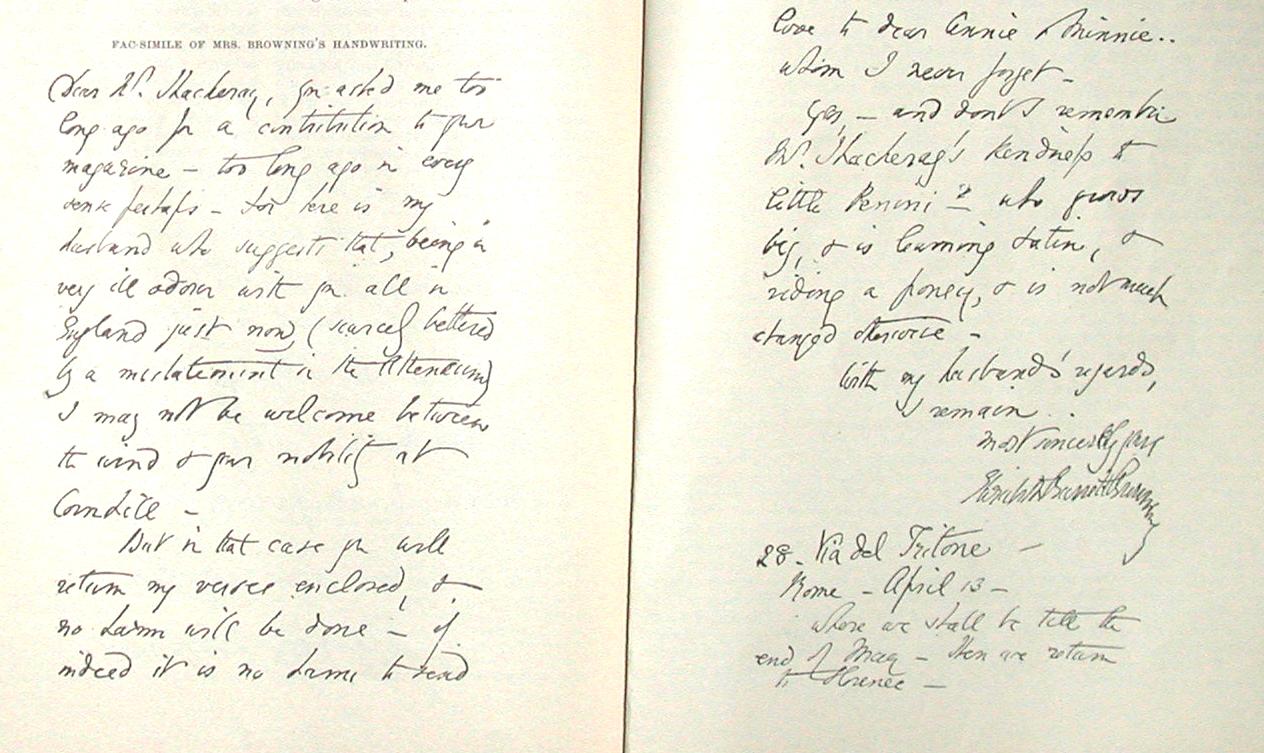

in the black dress, the writing apparatus by the sofa, the tiny

inkstand, the quill nibbed pen - the unpretentious implements of

her magic. 'She was a little woman; she liked little things', Mr

Browning used to say. Her miniature editions of the classics are

still carefully preserved, with her name written in each in her

delicate, sensitive handwriting, and always with her husband's

name above her own, for she dedicated all her books to him. It

was a fancy that she had. Nor must his presence in the house be

forgotten any more than in the books - a spirited domination and

inspired common sense, which seemed to give a certain life to

her vaguer visions. But of these values Mrs Browning rarely

spoke: she was too simple and practical to indulge in many

apostrophes.

II

To all of us who have only known Mrs Browning in

her own home as a wife and a mother, it seems almost impossible

to realize the time before her home existed - when Mrs Browning

was not, and Elizabeth Barrett, dwelling apart, was weaving her

spells like the Lady of Shalott, and subject, like the lady

herself, to the visions in her mirror.

Mrs Browning*/*The

facts and passages relating to Mrs Browning's early life are

taken (by the kind permission of the proprietors and editor)

from an article contributed by the present writer to the Biographical Dictionary

published by Messrs Smith, Elder, and Co.)/ was born in

the county of Durham, on the 6th of March, 1809 [actually 1806]. It

was a golden year for poets, for it was also that of Tennyson's

birth. She was the eldest daughter of Edward Moulton and was

christened by the names of Elizabeth Barrett. Not long after her

birth, Mr Moulton, succeeding to some property, took the name of

Barrettt, so that in after-times, when Mrs Browning signed

herself at length as Elizabeth Barrett Browning it was her own

Christian name that she used without any further literary

assumptions. Her mother was a Mary Graham, the daughter of a Mr

Graham, afterwards known as Mr Graham Clark of Northumberland.

Soon after the child's birth, her parents brought her southward,

to Hope End, near Ledbury, in Herefordshire, where Mr Barrett

now possessed a considerable estate, and had built himself a

country house. The house is now pulled down, but it is described

by one of the family as 'a luxurious home standing in a lovely

park, among trees and sloping hills all sprinkled with sheep';

and this same lady remembers the great hall, with the great

organ in it, and more especially Elizabeth's room, a lofty

chamber, with a stained glass window, casting lights across the

floor, and little Elizabeth as she used to sit propped against

the wall, with her hair falling all about her face. There were

gardens round about the house leading to the park. Most of the

children had their own plots to cultivate, and Elizabeth was

famed among them all for success with her white roses. She had a

bower of her own all overgrown with them: it is still blooming

for the readers of the lost bower 'as once beneath the

sunshine'. Another favorite device with the child was that of a

man of flowers, laid out in beds upon the lawn - a huge giant

wrought of blossom. 'Eyes of gentianella azure, staring, winking

at the sun'.

Mr Barrett was a rich man, and his daughter's life was that of a

rich man's child, far removed from the stress, and also from the

variety and experience of humbler life; but her eager spirit

found adventure for itself. Her gift for learning was

extraordinary. At eight years old little Elizabeth had a tutor

and could read Homer in the original, holding her book in one

hand and nursing her doll on the other arm. She has said herself

that in those days 'the Greeks were her demi-gods; she dreamed

more of Agamemnon than of Moses, her black pony'. At the same

small age she began to try her childish powers. When she was

about eleven or twelve her great epic of the battle of Marathon

was written in four books, and her proud father had it printed.

'Papa was bent upon spoiling me', she writes. Her cousin

remembers a certain ode the little girl recited to her father on

his birthday; as he listened, shutting his eyes, the young

cousin was wondering why the tears came falling along his cheek.

It seems right to add, on this same authority, that their common

grandmother, who used to stay at the house, did not approve of

these readings and writings, and said she had far rather see

Elizabeth's hemming more carefully finished off than hear of all

this Greek.

Elizabeth was growing up meanwhile under happy influences; she

had brothers and sisters in her home, her life was not all

study, she had the best of company, that of happy children as

well as of all natural things; she loved her hills, her gardens,

her woodland play ground. As she grew older she used to drive a

pony and go farther afield. There is a story still told of a

little girl, flying in terror along one of the steep

Herefordshire lanes, perhaps frightened by a cow's horn beyond

the hedge, who was overtaken by a young girl, with a pale

spiritual face and a profusion of dark curls, driving a pony

carriage, and suddenly caught up into safety and driven rapidly

away. These scenes are turned to account in 'Aurora Leigh'. Very

early in life the happy drives and rides were discontinued, and

the sad apprenticeship to suffering began. It probably was

Moses, the black pony, who was so nearly the cause of her death.

One day, when she was about fifteen, the young girl, impatient,

tried to saddle her pony in a field alone, and fell, with the

saddle upon her, in some way injuring her spine so seriously

that she lay for years upon her back.

She was about twenty when her mother's last illness began, and

at the same time some money catastrophes, the result of other

people's misdeeds, overtook Mr Barrett. He would not allow his

wife to be troubled or to be told of this crisis in his affairs,

and he compounded with his creditors at an enormous cost,

materially diminishing his income for life, so as to put off any

change to the ways at Hope End until change could trouble the

sick lady no more. After her death, when Elizabeth was a little

over twenty, they came away, leaving Hope End among the hills

forever. 'Beautiful, beautiful hills', Miss Barrett wrote long

after from her closed sick-room in London, 'and yet not for the

whole world's beauty would I stand among the sunshine and shadow

of them any more; it would be a mockery, like the taking back a

broken flower to its stalk'.

The family spent two years at Sidmouth, and then came to London,

where Mr Barrett first bought a house in Gloucester Place, and

then removed to Wimpole Street. His daughter's continued

delicacy and failure of health kept her for months at a time a

prisoner to her room, but did not prevent her from living her

own life of eager and beautiful aspiration. She was becoming

known to the world. Her 'Prometheus' which was published when

she was twenty-six years old, was reviewed in the Quarterly Review for 1840

and there Miss Barrett's name comes second among a list of the

most accomplished women of those days, whose little tinkling

guitars are scarcely audible now, while this one voice vibrates

only more clearly as the echoes of her time die away.

Her noble poem on 'Cowper's Grave' was republished with the

'Seraphim', by which (whatever her later opinion may have been)

she seems to have set small count at the time, 'all the

remaining copies of the book being locked away in the wardrobe

in her father's bedroom', 'entombed as safely as Oedipus among

the olives'.

From Wimpole Street Miss Barrett, went, an unwilling exile for

her health's sake, to Torquay, where the tragedy occurred which,

as she writes to Mr Horne, 'gave a nightmare to her life

forever'. Her companion-brother had come to see her and to be

with her and to be comforted by her for some trouble of his own,

when he was accidentally drowned, under circumstances of

suspense which added to the shock. All that year the sea beating

upon the shore sounded to her as a dirge, she says, in a letter

to Miss Mitford. It was long before Miss Barrett's health was

sufficiently restored to allow of her being brought hom to

Wimpole Street, where many years passed away in confinement to a

sick room, to which few besides members of her own family were

admitted. Among these exceptions was her devoted Miss Mitford

who would 'travel forty miles to see her for an hour'. Besides

Miss Mitford, Mrs Jameson also came, and above all, Mr Kenyon,

the friend and dearest cousin, to whom Mrs Browning afterwards

dedicated 'Aurora Leigh'. Mr Kenyon had an almost fatherly

affection for her, and from the first recognized his young

relative's genius. He was a constant visitor and her link with

the outside world, and he never failed to urge her to write, and

to live out and beyond the walls of her chamber.

As Miss Barrett lay on her couch with her dog Flush at her feet,

Miss Mitford describes her as reading every book in almost every

language, and giving herself heart and soul to poetry. She also

occupied herself with prose writing literary articles for the Athenaeum and contributing

to a modern rendering of Chaucer which

was then being edited by her unknown friend Mr. H.H. Horne, from

whose correspondence with her I have already quoted, and whose

interest in literature and occupation with literary things must

have brought wholesome distraction to the monotonies of her

life.

But such a woman, though living so quietly and thus secluded

from the world, could not have been altogether out of touch with

its changing impressions. The early letters of Mrs Browning's to

Mr Horne, written before her marriage, and published with her

husband's sanction after her death, are full of the suggestions

of her delightful fancy. Take, for instance, 'Sappho, who broke

off a fragment of her soul for us to guess at'. Of herself, she

says (apparantly in answer to some questions), 'my story amounts

to the knife-grinder's, with nothing at all for a catastrophe: A bird in a cage would have as

good a story; most all my events and nearly all my intense

pleasures have passed in my thoughts'. Here is another

instance of her unconscious presence in the minds of others. 'I

remember all those sad circumstances connected with the last

doings of poor Haydon'. Mr Browning writes to Professor Knight

in 1882. 'He never saw my wife, but interchanged letters with

her occasionally. On visiting her the day before the painter's

death, I found her couch occupied by a quantity of studies -

sketches and portraits - which, together with paints, pallettes,

and brushes he had chosen to send in apprehension of an arrest,

an execution in his own house. The letter which apprised her of

this step said, in excuse of it, 'they may have a right to my

goods: they can have none to my mere work tools and necessities

of existence', or words to that effect. The next morning I read

the account in the Times,

and myself happened to break the news at Wimpole Street, but had

been anticipated. Every article was at once sent back, no doubt.

I do not remember noticing Wordsworth's portrait - it never

belonged to my wife certainly, at any time. She possessed an

engraving of the head: I suppose a gift from poor Haydon'.

III

My friend Professor Knight has kindly

given me leave to quote from some of his letters from Robert

Browning. One most interesting record describes the poet's own

first acquaintance with Mr Kenyon. The letter is dated January

the 10th, 1884; but the events related, of course, to some forty

years before.

With respect to the

information you desire about Mr Kenyon, all that I do 'know of

him - better than anybody', perhaps - is his great goodness to

myself. Singularly, little respecting his early life came to

my knowledge. He was the cousin of Mr Barrett; second cousin,

therefore, of my wife, to whom he was ever deeply attached. I

first met him at a dinner at Sergeant Talfourd's, after which

he drew his chair by mine and inquired whether my father had

been his old school-fellow and friend at Cheshunt, adding

that, in a poem just printed, he had been commemorating their

play-ground fights, armed with sword and shield, as Achilles

and Hector, some half-century before. On telling this to my

father at breakfast next morning, he at once, with a pencil

sketched me the boy's handsome face, still distinguishable in

the elderly gentleman's I had made acquaintance with. Mr

Kenyon at once renewed his own acquaintance with my father and

became my fast friend; hence my introduction to Miss Barrett.

He was one of the best of human

beings, with a general sympathy for excellence of every kind.

He enjoyed the friendship of Wordsworth, of Southey, of

Landor; and, in later days, was intimate with most of my own

contemporaries of eminence. I believe that he was born in the

West Indies, whence his property was derived, as was that of

Mr Barrett, persistently styled as a 'merchant' by biographers

who will not take the pains to do more than copy the blunders

of their forerunners in the business of article-mongery. He

was twice-married, but left no family. I should suggest Mr

Scharf (of the National Portrait Gallery) as a far more

qualified informant on all such matters, my own concern having

mainly been with his exceeding goodness to me and mine'.

IV

When Mrs Orr's admirable history of Robert

Browning appeared, the writer felt that it was but waste of time

to attempt anything like a biographical record. Others, with

more knowledge of his early days, have described Robert Browning

as a child, as a boy, and a very young man. How touching, among

other things, is the account of the little child among his

animals and pets; and of the tender mother taking so much pains

to find the original editions of Shelley and Keats, and giving

them to her boy at a time when their works were scarcely to be

bought! This much I will just note, that Browning was a year

younger than my own father, and was born at Camberwell in May,

1812. He went to Italy when he was twenty years of age, and

there he studied hard, laying in a noble treasury of facts and

fancies to be dealt out in after-life, when the time comes to

draw upon the past, upon that youth which age spends liberally,

and which is 'the background of pale gold' upon which all our

lives are painted.

Browning's first published poem was 'Pauline', coming out in the

same year as the 'Miller's Daughter' and the 'Dream of Fair

Women'. And we are also told that Dante Rossetti, then a very

young man, admired 'Pauline' so much that he copied the whole

poem out from the book in the British Museum.* /*The writer has in her

possession a book in which her own father, somewhere about the

same year, copied out Tennyson's 'Day Dream' verse by verse./

In 1834 Robert Browning went to Russia, and there wrote

'Porphyria's Love', published by Mr Jonathan Fox in a Unitarian

magazine, where the poem must have looked somewhat out of place.

It was at Mr Fox's house that Browning first met Macready.

Notwithstanding many differences and consequent estrangements, I

have often heard Mr Browning speak of the great actor with

interest and sympathy, the last time being when Recollections of Macready,

a book of Lady Pollock's, had just come out. She had sent Mr

Browning a copy, with which he was delighted, and he quoted page

after page from memory. His memory was to the last most

remarkable.

There is a touching passage in Mrs Orr's book describing the

meeting of Browning and Macready after their long years of

estrangement. Both had seen their homes wrecked and desolate;

both had passed through deep waters. They met unexpectedly and

held each other's hands again. 'Oh, Macready', said Browning.

And neither of them could speak another word.

As we all know, it was Mr Kenyon who first introduced Robert

Browning to his future wife; and the story, as told by Mrs Orr,

is most romantic. The poet was about thirty-two years of age at

this time in the fulness of his powers. She was supposed to be a

confirmed invalid, confined to her own room and to her couch,

seeing no one, living her own spiritual life, indeed, but

looking for none other, when Mr Kenyon first brought Mr Browning

to her father's house. Miss Barrett's reputation was well

established by this time. 'Lady Geraldine's Courtship' was

already published, in which the author had written of Browning

among other poets as of 'some pomegranate, which,deep down the

middle, shows a heart within blood-tinctured, of a veined

humanity'; and one can well believe that this present meeting

must have been but a phase in an old and long-existing sympathy

between kindred spirits. Very soon afterwards the poets became

engaged, and they were married in the autum of the year 1846.

Who does not know the story of this marriage of true souls? Has

not Mrs Browning herself spoken of it in words indelible and

never to be quoted without sympathy by all women? while he from

his own fireside has struck chord after chord of manly feeling

than which this life contains nothing deeper or more true.

The sonnets from the Portuguese were written by Elizabeth

Barrett to Mr Browning before her marriage, although she never

even showed them to him till some years after they were man and

wife. They were sonnets such as no Portuguese ever wrote before,

or ever will write again. There is a quality in them which is

beyond words, that echo which belongs to the highest expression

of feeling. But such a love to such a woman comes with its own

testament.

Some years before her marriage the doctors had positively

declared that Miss Barrett's life depended upon her leaving

England for the winter, and immediately after their marriage Mr

Browning took his wife abroad.

Mrs Jameson was at Paris when Mr

and Mrs Browning arrived there. There is an interesting account*

/Life of Mrs Jameson,

by Mrs Macpherson./ of the meeting, and of their all

journeying together southwards by Avignon and Vaucluse. Can this

be the life-long invalid of whom we read, perching out-of-doors

upon a rock, among the shallow curling waters of a stream? They

come to a rest at Pisa, whence Mrs Browning writes to her old

friend Mr Horne, to tell him of her marriage, adding that Mrs

Jameson calls her, notwithstanding all the emotion and fatigue

of the last six weeks, rather 'transformed' than improved. From

Pisa the new married pair went Florence, where they finally

settled, and where their boy was born in 1849.

Poets are painters in words, and the color and the atmosphere of

the country to which they belong seem to be repeated almost

unconsciously in their work and its setting. Mrs Browning was an

English woman; though she lived in Italy, though she died in

Florence, though she loved the land of her adoption, yet she

never, for all that, ceased to breathe her native air as she sat

by the Casa Guidi windows; and though Italian sunshine dazzled

her dark eyes, and Italian voices echoed in the street, though

her very ink was mixed with the waters of the Arno, she still

wrote of Herefordshire lakes and hills, of the green land, where

'jocund childhood' played, 'dimpled close with hill and valley,

dappled very close with shade' . . . Now that the writer has

seen the first home and the last home of that kind friend of her

girlhood, it seems to her as if she could better listen to that

poet's song, growing sweeter, as all true music does, with

years.

We had been spending an autumn month in Mrs Browning's country

when we drove to visit the scene of her early youth, and it

seemed to me as if an echo of her melody was still vibrating

from hedge-row to hedge-row, even though the birds were silent,

and though summer and singing-time was over. We drove along, my

little son and I, towards Hope End, by a road descending

gradually from the range of the Malvern Hills into the valley;

it ran across commons sprinkled with geese and with lively

donkeys, and skirted by the cottages still alight with

sunflowers and nasturtium beds, for they were sheltered from the

cold wind by the range of purple hills 'looming arow'; then we

dipped into lanes between high banks heaped with ferns and

leaves of every shade of burnished gold and brown, fenced up by

the twisting roots of the chestnuts and oaktrees; and all along

the way, as our old white horse jogged steadily on, we could see

the briers and the blackberry sprays travelling too, advancing

from tree to tree, and from hedge to hedge, flashing their long

flaming brands and warning tokens of winter's approaching

armies. The wind was cold and in the north: the sky overhead was

broken and stormy. Sometimes we dived into sudden glooms among

rocks overhung with ivy and thich brushwood, then we came out

into an open space again, and caught sight of vast skies dashed

with strange lights, of a wonderful cloud-capped country up

above that seemed to reach from ocean to ocean, while the

storm-clouds reared their vast piles out of those sapphire

depths. Our adventures were not along the road, but chiefly

overhead. My boy amused himself by counting the broken rainbows

and the hail-storms falling in the distance; and then at last,

just as we were getting cold and tired, we turned into the lodge

gates of Hope End.

I don't know how this park strikes other people; to me, who paid

this one short visit, it seemed a sort of enchanted garden

revealed for an hour, and I almost expected that it would then

vanish away.*/*

Here's the garden she walked

across . . .

Down this side of

the gravel-walk

She went, while her robe's

edge brushed the box:

And here she paused in her

gracious talk

To point me a moth on the

milk-white flox.

Roses ranged in valiant

row,

I will never think she

passed you by'

'Garden Fancies', R.B./

The green sides of the hills sloped down into the

garden, and rose again crowned with pine trees: everything was

wild, abrupt, and yet suddenly harmonious. We passed an

unsuspected lake covered with water-lilies. A flock of sheep at

full gallop plunged across the road, then came ponies with long

manes and round wondering eyes trotting after us. Sometimes in

the Alps one has met such herds, wild creatures, sympathetic,

not yet afraid! Finally came a sight of the

river, where a couple of water-fowl were flying into the sedges.

But where was the wild swan's nest? and why was not the great

god Pan there to welcome us? It

all seemed so natural and so vivid that I should not have been

startled to see him sitting there by the side of the river.

IV

The only memorandum I ever made of Mrs Browning's

talk was when I was about sixteen years old, and I heard her

saying of some one else. 'That without illness, she saw no

reason why the mind should ever fail'. The visitor to whom she

was talking seems to have come away complaining that the

conversation had been too matter-of-fact, too much to the point:

nothing romantic, nothing poetic, such as one might expect from

a poet! Another person also present had answered that was just

the reason of Mrs Browning's power - she kept her poetry for her

poetry, and didn't scatter it about where it was not wanted; and

then comes a girlish note: 'I think Mrs Browning is the greatest

woman I ever saw in all my life. She is very small; she is

brown, with dark eyes and dead brown hair; she has white teeth

and a low, curious voice; she has a manner full of charm and

kindness; she rarely laughs, but is always cheerful and smiling;

her eyes are very bright. Her husband is not unlike her. He is

short; he is dark, with a frank open countenance, long hair

streaked with gray; he opens his mouth wide when he speaks; he

has white teeth'.

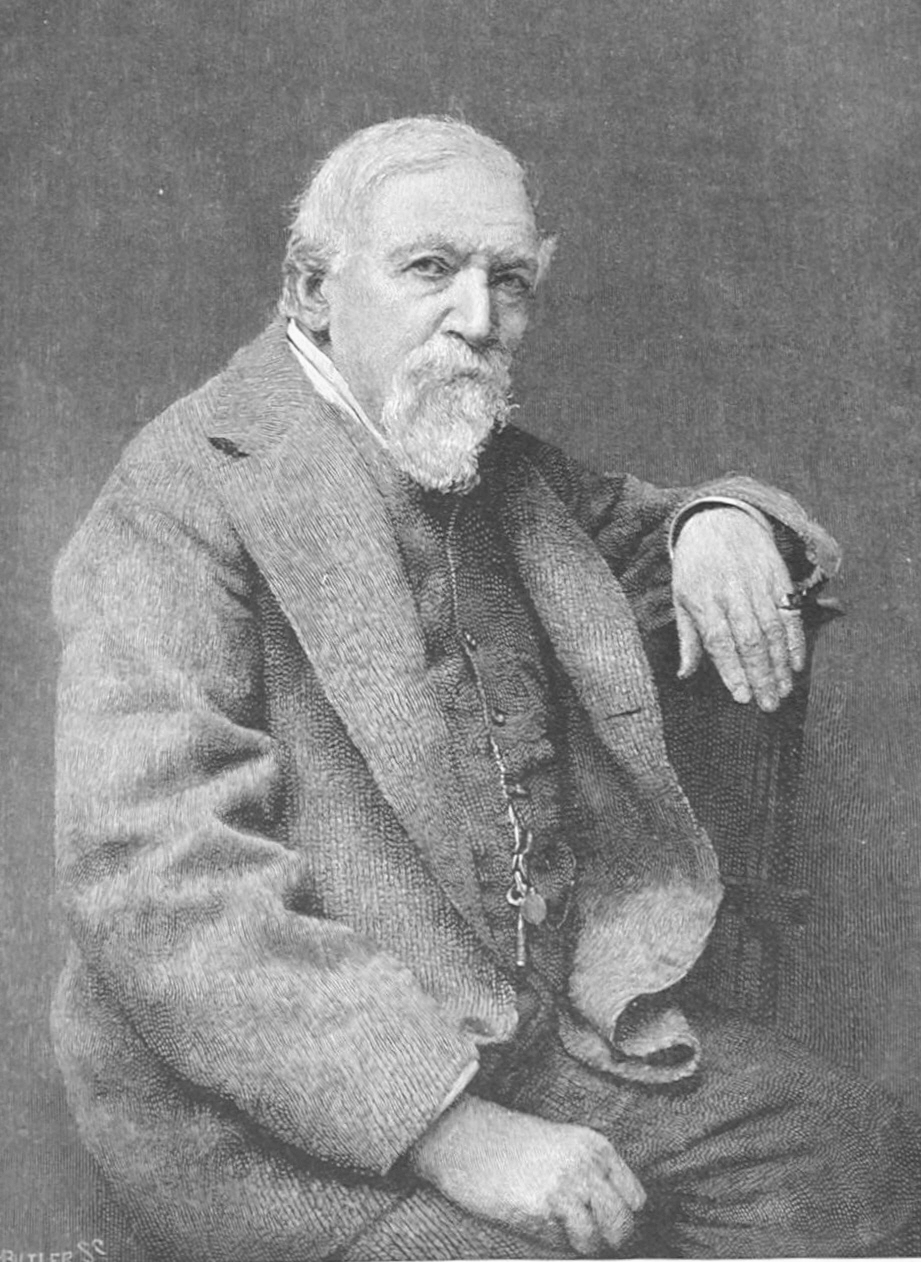

When I first remember Mr Browning he was a comparatively young

man - though, for the matter of that he was always young, as his

father had been before him - and he was also happy in this, that

the length of his life can best be measured by his work. In

those days I had not read one single word of his poetry, but

somehow realized that it was there.*/*An incidental allusion in Mrs Orr's life of

Browning has only recalled my own vivid impression of the

happy relations between my father and Mrs Browning./ Almost the first

time I ever really recall Mr Browning, he and my father and Mrs

Browning were discussing spiritualism in a very human and

material fashion, each holding to their own point of view, and

my sister and I sat by listening and silent. My father was

always immensely interested by the stories thus told, though he

certainly did not believe in them. Mrs Browning believed, and Mr

Browning was always irritated beyond patience by the subject. I

can remember her voice, a sort of faint minor chord, as she,

lisping the 'r' a little, uttered her remonstrating 'Robert!'

and his loud dominant barytone sweeping away every possible plea

she and my father could make; and then came my father's

deliberate notes, which seemed to fall a little sadly - his

voice always sounded a little sad - upon the rising waves of the

discussion. I think this must have been just before we all went

to Rome: it was in the morning, in some foreign city. I can see

Mr and Mrs Browning, with their faces turned towards the window,

and my father with his back to it, and all of us assembled in a

little high-up room. Mr Browning was dressed in a brown rough

suit, and his hair was black then: and she, as far as I can

remember, was, as usual, in soft-falling flounces of black silk,

and with her heavy curls drooping, and a tin gold chain round

her neck.

In the winter of 1853-4 we lived in Rome, in the Via della

Croce, and the Brownings lived in the Bocca di Leone hard by.

The evenings our father dined away from home our old donna (so I

think cooks used to be called) would conduct us to our tranquil

dissipations, through the dark streets, past the swinging lamps,

up and down the black stone staircases; and very frequently we

spent an evening with Mrs Browning in her quiet room, while Mr

Browning was out visiting some of the many friends who were

assembled in Rome that year. At ten o'clock came our father's

servant to fetch us back, with the huge key of our own somewhat

imposing palazzo. It was a happy and eventful time, all the more

eventful and happy to us for the presence of the two kind

ladies, Mrs Browning and Mrs Sartoris, who befriended us.

I can also remember one special evening at Mrs Sartoris's, when

a certain number of people were sitting just before dinner time

in one of those lofty Roman drawing-rooms, which become so

delightful when they are inhabited by English people, which look

so chill and formal in their natural condition. This saloon was

on the first floor, with great windows at the farthest end. It

was all full of a certain mingled atmosphere of flowers and

light, and comfort and color. It was in contrast but not out of

harmony with Mrs Browning's quiet room - in both places existed

the individuality which real home-makers know how to give to

their homes. Here swinging lamps were lighted up, beautiful

things hung on the walls, the music came and went as it listed,

a great piano was drawn out and open, the tables were piled with

books and flowers. Mrs Sartoris, the lady of the shrine, dressed

in some flowing pearly satin tea gown, was sitting by a round

table, reading to some other women who had come to see her. She

was reading from a book of poems which had lately appeared; and

as she read in her wonderful Muse-like way, she paused, she

re-read the words, and she emphasized the lines, then stopped

short, the others exclaiming, half laughing, half protesting . .

. It was a lively, excitable party, outstaying the usual hour of

a visit: questioning, puzzling, and discursive - a Browning

society of the past - into the midst of which a door opens (and

it is this fact which recalls it to my mind), and Mr Browning

himself walks in, and the burst of voices is suddenly reduced to

one single voice, that of the hostess, calling him to her side,

and asking him to define his meaning. But he evaded the

question, began to talk of something else - he never much cared

to talk of his own poetry - and the Browning society dispersed.

Mrs Sartoris used to describe many pleasant meetings between the

Brownings and themselves, and there is one particular festival

she used to like to speak of - a certain luncheon at their

house, which she always said was one of the most delightful

entertainments she could remember in all her life. One wonders

whether the guests or the hosts contributed most. Each one had

been happy and talked his or her best, and when the Sartorises

got up reluctantly to go, saying 'Come back to sup with us, do',

and Mrs Browning exclaimed, 'Oh, Robert, how can you ask them!

There is no supper, nothing but the remains of the pie'. And

then, cries Robert Browning, 'Well, come back and finish the

pie'.

The Pall Mall Gazette

of April 9, 1891 contains an amusing account of a journey from

London to Paris taken forty years ago by Mr and Mrs Browning.

The companion they carried with them writes of the expedition,

dating from Chelsea, September 4, 1851.

The day before yesterday, near midnight, I returned

from a very short and very insignificant excursion, which

after a month at Malvern water-cure and then a ten days at

Scotsbrig, concludes my travels for this year.

The chronicle begins on Monday, September 21st, when 'Brother

John' and Carlyle go to Chorley to consult about passports,

routes, and conditions . . .

At Chapman's shop I learned that Robert Browning

(poet) and his wife were just about setting out for Paris. I

walked to their place; had, during that day and following,

consultations with these fellow pilgrims, and decided to go

with them via Dieppe on Thursday . . .

Up,

according to Thursday morning, in mutterable flurry and tumult

- phenomena on the Thames all dreamlike, one spectralism

chasing another - to the station in good time; found the

Brownings just arriving, which seemed a good omen. Browning

with wife and child and maid, then an empty seat for cloaks

and baskets; lastly, at the opposite end from me, a

hard-faced, honest Englishman or Scotchman all in gray with a

gray cap, who looked rather ostrich-like, but proved very

harmless and quiet - this was the loading of our carriage; and

so away we went, Browning talking very loud and with vivacity,

I silent rather, tending towards many thoughts . . .

Our

friends, especially our French friends, were full of bustle,

full of noise, at starting; but so soon as we had cleared the

little channel of Newhaven and got into the sea or British

Channel all this abated, sank into the general sordid torpor

of seasickness, with its miserable noises - 'houhah, hoh!' -

and hardly any other, amid the rattling of the wind and sea. A

sorry phasis of humanity! Browning was sick - lay in one of

the bench tents horizontal, his wife below. I was not

absolutely sick, but had to be quite quiet and without

comfort, save in one cigar, for seven or eight hours of

blustering, spraying, and occasional rain.'

And so with mention of prostration into doleful silence, of

evanition into utter darkness, of the poor Frenchman who was so

lively at starting.

At Dieppe, while the others were in the hotel having

some very bad cold tea and colder coffee, Browning was passing

our luggage, brought it all in safe almost half past ten

o'clock, and we could address ourselves to repose. So to be in

my upper room, bemoaned by the sea and small incidental noises

of the harbor. Next morning Browning, as before, did

everything. I sat out-of-doors on some logs at my ease and

smoked, looking at the population and their ways. Browning

fought for us, and we - that is, the woman, the child, and I -

had only to wait and be silent. At Paris the travellers came

into a crowding, jingling, vociferous tumult, in which the

brave Browning fought for us, leaving me to sit beside the

woman'.

Mr Browning once told us a little anecdote of the Carlyles at

tea in Cheyne Row, and of Mrs Carlyle pouring out the tea, with

a brass kettle boiling on the hob, and Mr Browning presently

seeing that the kettle was needed, and that Carlyle was not

disposed to move, rose from his own chair, and filled the teapot

for his hostess, and then stood by her tea table still talking

and absently holding the smoking kettle in his hand.

'Can't you put it down?' said Mrs Carlyle, suddenly; and Mr

Browning, confused and somewhat absent, immediately popped the

kettle down upon the carpet, which was a new one.

Mrs Carlyle exclaimed in horror - I have no doubt she was half

laughing - 'See how fine he has grown! He does not any longer

know what to do with the kettle!'

And, sure enough, when Mr Browning penitently took it up again,

a brown oval mark was to be seen clearly stamped and burned upon

the new carpet. 'You can imagine what I felt', said Mr

Browning. 'Carlyle came to my rescue. 'Ye should have been more

explicit', said he to his wife'.

V

When my father

went for the second time to America in 1856, my sister and I

remained behind, and for a couple of days we staid on in our

home before going to Paris. Those days of parting are always sad

ones, and we were dismally moping about the house and preparing

for our own journey when we were immensely cheered by a visitor.

It was Mr Browning, who came in to see us, and who brought us an

affectionate little note from his wife. We were to go and spend

the evening with them, the kind people said. They had Mr

Kenyon's brougham at their disposal, and it would come and fetch

us and take us back at night, and so that first sad evening

passed far more happily than we would ever have imagined

possible. I remember feeling, as young people do, utterly,

hopelessly miserable, and then suddenly very cheerful every now

and then. I believe my father had planned it all with them

before he went away.

This was in the autumn of 1856, and 'Aurora Leigh' was published

in 1857. It must have been on the occasion of their journey home

to England that 'Aurora Leigh' was lost in its box at

Marseilles.

The box was at Marseilles where it had been left by some

oversight, and all the MSS had been packed in it. In this same

box were also carefully put away certain velvet suits and lace

collars, in which the little son was to make his appearance

among his English relatives. Mrs Browning's chief concern was

not for her MSS, but for the loss of her little boy's wardrobe,

which had been devised with so much motherly pride. Who could

blame her if her taste in boys' costume was somewhat too

fanciful and poetic for the days in which she lived!

Happily for the world at large, one of Mrs Browning's brothers

chanced to pass through the place, and the box was discovered by

him stowed away in a cellar at the customs.

We must have met again in Paris later in this same year. the

Brownings had an apartment near to Rond Point, where we used to

go and see them, only to find the same warm and tranquil

atmosphere that we used to breathe in Rome - the sofa drawn out,

the tiny lady in the corner, the afternoon sun dazzling in at

the window. One one occasion Mr Hamilton Aidé was paying a

visit. He had been talking about books, and, half laughing, he

turned to a young woman and asked her when her forthcoming

work would be ready, Young persons are ashamed, and very

properly so, of their early failures, of their pattés de mouches and wild

attempts at authorship, and this one was no exception to the

common law, and answered 'Never', somewhat too emphatically. And

then it was that Mr Browning spoke of one of those chance saying

which make headings to the chapters of one's life. 'All in good

time', he said, and he went on to ask us all if we remembered

the epitaph on the Roman lady who sat at home and span wool.

'You must spin your wool some day', he said kindly, to the

would-be authoress;' 'every woman has wool to spin of some sort

or another; isn't it so?' he said, and he turned to his wife.

I went home feeling quite impressed by the little speech, it had

been so gravely and kindly made. My blurred pages looked

altogether different, somehow. It was spinning wool - it was not

wasting one's time, one's temper - it was something more than

spoiling paper and pens. And this much I may perhaps add for the

comfort of the future race of the authoresses who are now

spinning the cocoons from which the fluttering butterflies and

Psyches yet to be will emerge upon their wings; never has

anything given more trouble or seemed more painfully hopeless

than those early incoherent pages, so full of meaning to one's

self, so absolutely idiotic in expression. In later life the

words come easily, only too readily; but then it is the meaning

which lags behind.

It was in that same apartment that I remember hearing Mr

Browning say (across all these long years): 'It may seem to you

strange that such a thing as poetry should be written with

regularity at the same hour in every day. But nevertheless I do

assure you it is a fact that my wife and I sit down every

morning after breakfast to our separate work; she writes in the

drawing-room and I write in here', he said, opening a door into

a little back empty room with a window over a court. And then he

added, 'I never read a word she writes until I see it all

finished and ready for publication'.

. . .

VI

It was in Florence

Mrs Browning wrote 'Casa Guidi Windows', containing the

wonderful description of the procession passing by and that

noble apostrophe to freedom beginning, 'O magi from the East and

from the West'. 'Aurora Leigh' was also written here, which the

author herself calls 'the most mature of her works', the one

into which her highest convictions have entered. The poem is

full of beauty from the first page to the last, and beats time

to a noble human heart. the opening scenes in Italy, the

impression of light, of silence; the beautiful Italian mother;

the austere father with his open books; the death of the mother,

who lies laid out for burial in her red silk dress; the epitaph

'Weep for an infant too young to weep much when Death removed

this mother'. Auora's journey to her father's old home; her

lonely terror of England; her slow yielding to its silent

beauty; her friendship with her cousin, Romney Leigh; their

saddening, widening knowledge of the burthen and sorrow of life,

and the way this knowledge influences both their fates - all is

described with that irresistable fervor which is the translation

of the essence of things into words.

Mrs Browning was a great writer, but I think she was even more a

wife and a mother than a writer, and any account of her would be

incomplete which did not put these facts first and foremost in

her history.

The author of 'Aurora Leigh' once added a characteristic page to

one of her husband's letters to Leigh Hunt. She has been telling

him of her little boy's illness. 'You are aware that that child

I am more proud of than of twenty "Auroras" even after Leigh

Hunt has praised them. When he was ill he said to me, 'You pet,

don't be unhappy about me, think it's only a boy in the street,

and be a little sorry, but not unhappy'. Who could not be

unhappy, I wonder! . . . I never saw your book called The Religion of the Heart.

I receive more dogma, perhaps (my 'perhaps' being in the dark

rather), than you do'.

She says in conclusion, 'Churches do all of them, as at present

constituted, seem too narrow and low to hold true Christianity

in its proximate development - I at least cannot help believing

them so'.

She seemed, even in her life, something of a spirit, as her

friend had said, and her view of life's sorrow and shame, of its

beauty and eternal hope, is not unlike that which one might

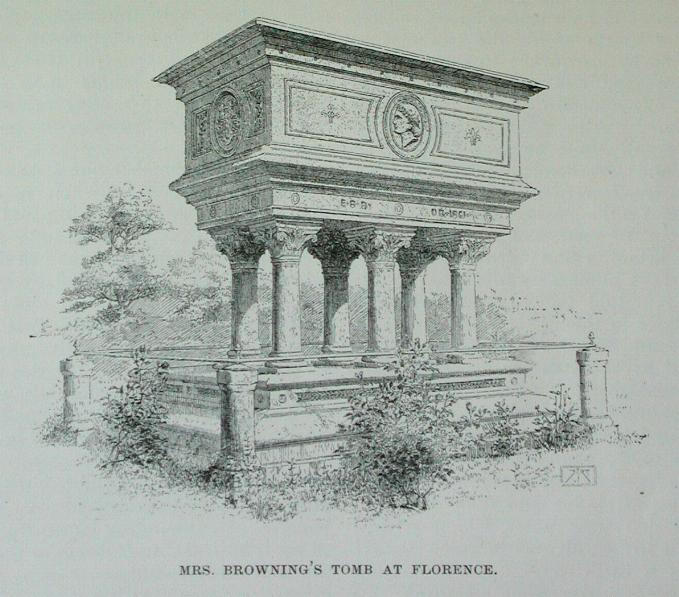

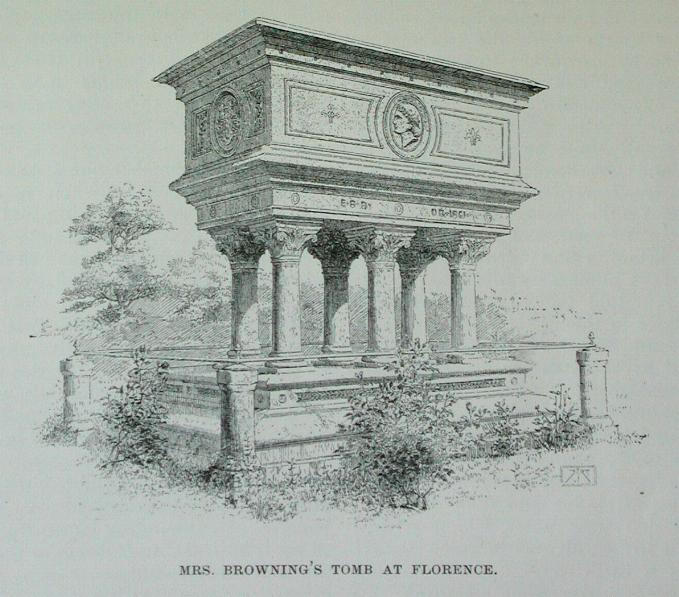

imagine a spirit's to be. She died at Florence in 1861. It is

impossible to read without emotion the account of her last hours

as it is given in Robert Browning's life.

A tablet has been placed on Casa Guidi, voted by the

municipality of Florence, and written by Tommaseo:

Here wrote and died Elizabeth

Barrett Browning, whose woman's heart combined the wisdom of a

wise man with the genius of a poet, and whose poems form a

golden ring which joins Italy to England. The town of

Florence, ever grateful to her, has placed this epitaph to her

memory.

There was a woman living in Florence, an old friend, clever,

warm-hearted, Miss Isa Blagden, herself a writer, who went to Mr

Browning and his little boy in their terrible desolation, and

who did what little a friend could do to help them. Day after

day, and for two or three nights, she watched by the stricken

pair until she was relieved, then the father and the little son

came back to England. They settled near Miss Barrett, Mrs

Browning's sister, who was living in Delamere Terrace, and upon

her own father's death, Miss Browning came to be friend,

home-maker, for her brother.

I can remember walking with my father under the trees of

Kensington Gardens when we met Mr Browning just after his return

to England. He was coming towards us along the broad walk in his

blackness through the sunshine. We were then living in Palace

Green, close by, and he came to see us very soon after. But he

was in a jarred and troubled state, and not himself as yet,

although I remember his speaking of the house he had just taken

for himself and his boy. This was only a short time before my

father's death. In 1864 my sister and I left our home and went

abroad, nor did we all meet again for a very long time.

It was a mere chance, so Mr Browning once said, whether he

should live in this London house that he had taken, and join in

social life, or go away to some quiet retreat and be seen no

more; but for great poets, as for small ones, events shape

themselves by degrees, and after the first hard years of his

return a new and gentler day began to dawn for him. Miss

Browning came to them; new interests arose; acquaintances

ripened to friends (this blessed human fruit takes time to

mature); his work and his influence spread.

He published some of his finest work about this time. 'Dramatis

Personae', a great part of which had been written before, came

out in 1864; then followed the 'Ring and the Book', published by

his good friend, and ours, Mr George Murray Smith, and

'Balustion' in 1871. Recognition, popularity, honorary degrees,

all the tokens of appreciation, which should have come sooner,

now began to crowd in upon him, lord rectorships, and

fellowships, and dignities of every sort. He went his own way

through it all, cordially accepted the recognition, but chiefly

avoided the dignities and kept his two lives distinct. He had

his public life and his own private life, with its natural

interests and outcoming friendships and constant alternate pulse

of work and play.

VII

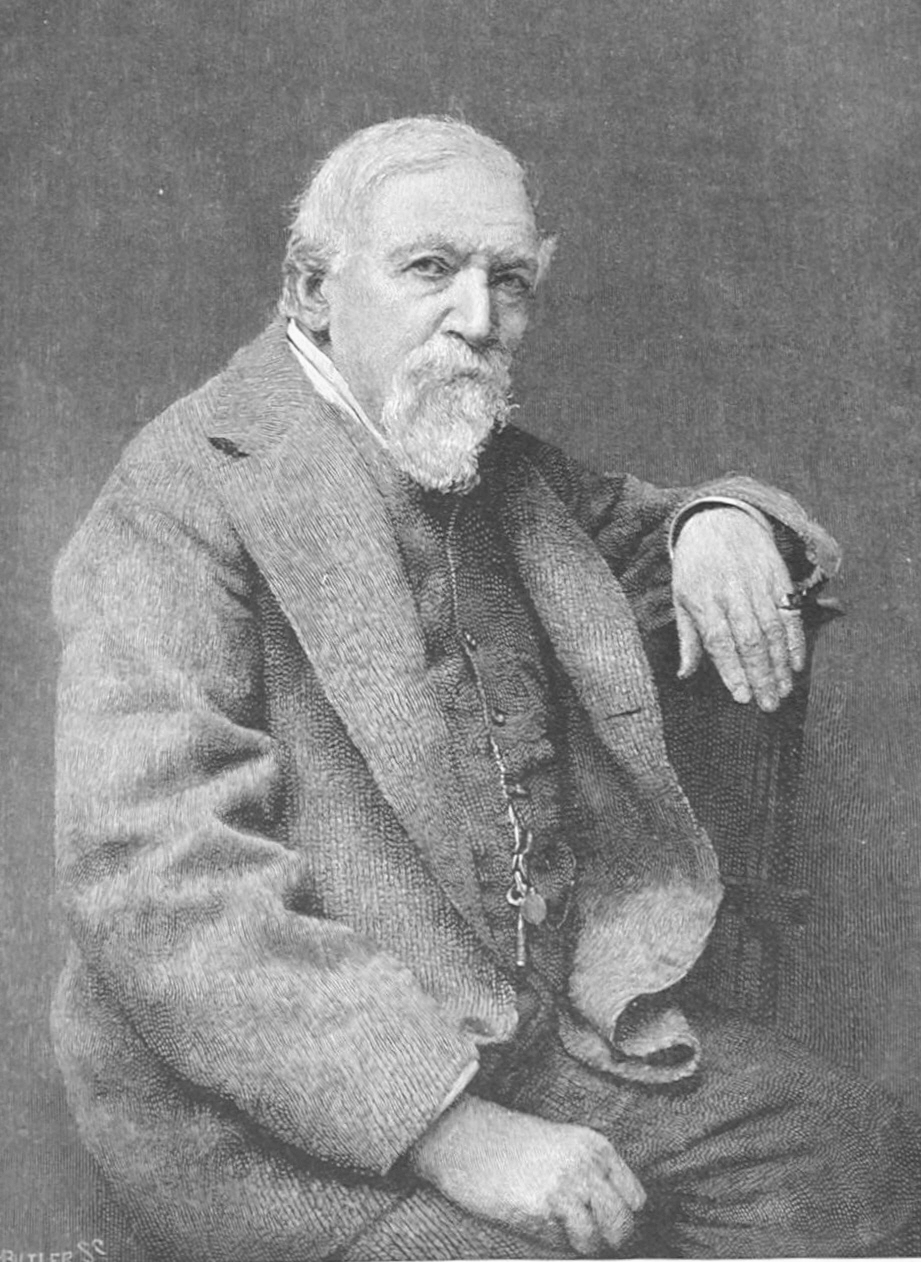

Browning has been

described as looking something like a hale naval officer; but in

later life, when his hair turned snowy white, he seemed to me

more like some sage of by-gone ages. There was a statue in the

Capitol of Rome to which Mrs Sartoris always likened him. I

cannot imagine that any draped and filleted companion, so racy,

so unselfishly interested in the events of the hour as he. 'He

was not only ready for talk, but fond of it', said a writer in

the Standard. 'He was absolutely unaffected in his choice of

topics; anything but the can of literary circles pleased him. If

only we knew a tithe of what he knew, and of what, unluckily, he

gives us credit for knowing, many a hint that serves only to

obscure the sense would be clear enough', says the same writer,

with no little truth.

Among Browning's many gifts that of delightful story-telling is

certainly one which should not be passed over. His memory was

very remarkable for certain things; general facts, odds and ends

of rhyme and doggerel, bits of recondite knowledge, came back to

him spontaneously and with vivacity. This is all to be noticed

in his books, which treat of so many quaint facts and theories.

His stories were especially delightful, because they were told

so appositely, and were so simple and complete in themselves. .

. .

Another reminiscence which my friend Mrs C - recalls is in a

sadder strain. It was a description of something Mr Browning

once saw in Italy. It happened at Arezzo, where he had turned by

chance into an old church among the many old churches there,

that he saw a crowd of people at the end of an aisle, and found

they were looking at the skeleton of a man just discovered by

some workmen who were breaking away a portion of the wall

opposite the high altar. The skin was like brown leather, but

the features were distinguishable. Mr Browning made inquiries as

to who it was. He could hear of no tradition even of a man

beikng walled up. The priests thought it must been done three or

four hundred years ago. A hole had been left above his head to

enable him to breathe. Mr Browning said the dead man was

standing with his hands crossed upon his breast, on the face was

a look of expectation, a expression of hoping against hope. The

man looked up, knowing help could only come from above, and must

have died still hoping. Mrs. C - said to Mr Browning she

wondered he had not written a poem about. He replied he had done so, and had given

it away.

I often find myself going back to Darwin's saying about the

duration of a man's friendships being one of the best measures

of his worth, and Browning's friendships are very

characteristic. He specially loved Landor.

For the Tennysons his was also a real and deep affection. Was

there ever a happier, truer dedication than that of his

collected selections? -

To Alfred Tennyson

In poetry

illustrious and consummate.

In friendship noble and sincere.

VIII

Besides the

actual personal feelings, there are the affinities of a life

to be taken into account. the following passages, which I

owe to Professor Knight's kindness, are very remarkable, for

they show what Browning's estimation was of Wordsworth, and

although they were not written till much later, I give them

here. Indeed the point of meeting of these two beneficent

poet streams is one full of interest to those upon the

shore. The first paragraph of the first letter relates to

some new honors and dignities gratefully but firmly

declined.

March 21st '83. - I do feel increasingly

(cowardly as seems the avowal) the need of keeping the

quiet corner in the world's van which I have got used to

for so many years . . .

I

will as you desire, attempt to pick out the twenty poems

which strike me (and so as to take away my breath) as

those worthiest of the master Wordsworth.

Speaking

of a classification of Wordsworth's poems, in my heart I

fear I should do it almost chronologically, so

immeasurably superior seem to be the first sprighly

runnings. Your selection would appear to be excellent, and

the partial admittance of the later work prevents one from

observing the too definitely distinguishing black line

between supremely good and - well, what is fairly

tolerable from Wordsworty, always understand.

To one of the letters addressed to Professor Knight there is

this touching postscript:

I open the envelope to say - what I had

nearly omitted - that Ld Coleridge proposed, and my humble

self - at his desire - seconded you, last evening, for

admission to the Atheneaum. I had the less scruple in

offering my services that you will most likely never see

in the offer anything but a record of my respect and

regard, since your election will come on when I shall be -

dare I hope? - 'elect' in even a higher society?

. . .

X

The visit to St

Aubin was followed by 'Red Cotton Nightcap Country', and on

this occasion I must break my rule, and trench upon the

ground traversed by Mrs Orr. I cannot give myself greater

pleasure than by quoting the following passages from the Life:

The August of 1872 and of 1873 again

found him and his sister at St Aubin, and the earlier

visit was an important one, since it supplied him with the

materials of his next work, of which Miss Annie Thackaray,

there also for a few days, suggested the title. The tragic

drama which forms the subject of Mr Browning's

poem had been in great part enacted in the vicinity of St

Aubin, and the case of disputed inheritance to which it

had given rise was pending at that moment in the tribunals

of Caen. The prevailing impression left on Miss

Thackeray's mind by this primitive district was, she

declared, that of white cotton nightcaps (the habitual

head-gear of the Normandy peasants). She engaged to write

a story called 'White Cotton Nightcap Country', and Mr

Browning's quick sense of both contrast and analogy

inspired the introduction of this element of repose into

his own picture of that peaceful prosaic existence, and of

the ghostly, spiritual conflict to which it had served as

background. He employed a good deal of perhaps strained

ingenuity in the opening pages of the work in making the

white nightcap foreshadow the red, itself the symbol of

liberty, and only indirectly connected with tragic events;

and he would, I think, have emphasized the irony of

circumstance in a manner more characteristic of himself it

he had laid his stress on the remoteness from 'the madding

crowd', and repeated Miss Thackeray's title. There can,

however, be no doubt that his poetic imagination, no less

than his human insight, was amply vindicated by his

treatment of the story.

And perhaps the writer may be excused for inserting here a

letter which concerns the dedication of 'Red Cotton Nightcap

Country' - a very unexpected and delightful consequence of

our friendly meeting.

May 9, 1873

Dear Miss Thackeray, - Indeed the only

sort of pain that any sort of criticism could give me

would be by the reflection of any particle of pain it

managed to give you.

I dare say that by long use I don't feel or attempt to

feel criticisms of this kind, as most people might.

Remember that everybody this thirty years has given me his

kick and gone his way, just as I am told the understood

duty of all highway travellers in Spain is to bestow at

least one friendly thump for the mayoral's sake on his

horses as they toil along up the hill, 'so utterly a

puzzle', 'organ-grinding', and so forth, come and go again

without much notice; but any poke at me which would touch

you, would vex me

indeed; therefore pray don't let my critics into that secret! Indeed I

thought the article highly complimentary which comes of

being in the category celebrated by Butler:

Some have been kicked till they know

[not] whether

The

shoe is Spanish or neat's leather.

You

see the little patch of velvet in the toe-piece of this

slipper seemed to tickle by comparison!

Ever

yours affectionately

Robert

Browning

But in spite of the past, Mr Browning had little to complain

of in his future critics. This is not an unappreciative age,

the only faith to be found with it is that there are too

many mouths using the same words over and over again, until

the expressions seem to lose their senses and fly about

quite giddily and at haphazard. The extraordinary publicity

in which our bodies live seems to frighten away our souls at

times; we are apt to stick to generalities, or to

well-hackneyed adjectives which have ceased to have much

meaning or responsibility; or if we try to describe our own

feelings, it is in terms which sometimes grow more and more

emphatic as they are less and less to the point. when we

come to say what is our simple and genuine conviction, the

effort is almost beyond us. The truth is too like

Cordelia's. That say that you have loved a man or a woman,

that you admire them and delight in their work, does not any

longer mean to you or to others what it means in fact. It

seems almost a test of Mr Browning's true greatness that the

love and the trust in his genius have survived the things

which have been said about it.

. . .

The house by the water-side in Warwick Crescent, which

Browning hastily took and in which he lived for many

years after his return to England, was a very charming

corner, I used to think. It was London, but London touched

by some indefinite romance: the canal used to look cool and

deep, the green trees used to shade the crescent; it seemed

a peaceful oasis after crossing that dreary Aeolia of

Paddington, with its many despairing shrieks and whirling

eddies. the house was an ordinary London house, but the

carved oak furniture and tapestries gave dignity to the long

drawing-rooms, and pictures and books lined the stairs. In

the garden at the back dwelt, at the time of which I am

writing, two weird gray geese, with quivering silver wings

and long throats, who used to come to meet their master

hissing and fluttering. When I said I liked the place, he

told us of some visitor from abroad, who had lately come to

see him, who also liked Warwick Crescent, and who, looking

up and down the long row of houses and porticoes in front of

the canal, said, 'Why, this is a mansion, sir; do you

inhabit the whole of this great building; and do you allow

the public to sail upon the water?'

As we sat at luncheon, I looked up and down the room, with

its comfortable lining of books, and also I could not help

noticing the chimney board heaped with invitations. I never

saw so many cards in my life before. Lothair himself might

have wondered at them.

Mr Browning talked on, not of the present London, but of

Italy and villegiatura

with his friends the Storys; of Siena days and of Walter Savage Landor. He told us the

piteous story of the old man wandering forlorn down the

street in the sunshine without a home to hide his head. He

kindled in the remembrance of the old poet, of whom he said

his was the most remarkable personality he had ever known;

and then, getting up abruptly from the table, he reached

down some of Landor's many books from the shelves near the

fireplace and said he knew no finer reading.

He read us some extract from the 'Conversations with the

Dead', quickly turning over the leaves, seeking for his

favorite passages.

There is a little anecdote which I think he also told us on

this occasion. It concerned a ring which he used to wear,

and which had belonged to his wife. One day in the Strand he

discovered that the intaglio from the setting was missing.

People were crowding in and out, there seemed no chance of

recovering; but all the same he retraced his steps, and lo!

in the centre of the crossing lay the jewel on a stone,

shining in the sun. He had lost the ring on a previous

occasion in Florence, and found it there by a happy chance.

XII

It was not until

1887 that Mr Browning moved to De Vere Gardens, where I saw

him almost for the last time. Once I remember calling there

at an early hour with my children. the servant hesitated

about letting us in. Kind Miss Browing came out to speak to

us, and would not hear of us going away.

'Wait a few minutes. I know he will see you', she said.

'Come in. Not into the dining-room; there are some ladies

waiting there; and there are some members of the Browning

Society in the drawing-room. Robert is in the study, with

some Americans who have come by appointment. Here is my

sitting-room', she said; 'he will come to you directly'.

We had not waited five minutes when the door opened wide and

Mr Browning came in. Alas! it was no longer the stalwart

visitor from St Aubin. He seemed tired, hurried, though not

less outcoming and cordial in his silver age.

'Well, what can I do for you?' he said, dropping into a

chair and holding out both his hands.

I told him it was a family festival and that I had 'brought

the children to ask for his blessing'.

Is that all?' he said, laughing, with a kind look, not

without some relief. He also hospitably detained us, and

when his American visitors were gone, took us in turn up

into his study, where the carved writing tables were covered

with letters - a milky way of letters, it seemed to me,

flowing in from every direction.

'What, all this to answer?' I exclaimed.

'You can have no conception what it is', he replied. 'I am

quite tired out with writing letters by the time I begin my

days' work'.

But his day's work was ending here. Soon afterward he went

to Italy and never returned in life. He closed his eyes in

his son's beautiful home at Venice among those he loved

best. His son, his sister, his daughter-in-law, were about

his bed tending and watching to the last.

When Spenser died in the street in Westminster in which he

dwelt after his home in Ireland was burnt and his child was

killed by the rebels, it is said that after lingering in

this world in poverty and neglect, he was carried to the

grave in state, and that his sorrowing brother poets came

and stood round about his grave, and each in turn flung in

an ode to his memory, together with the pen with which it

had been written. The present Dean of Westminster, quoting

this story, added that probably Shakespeare had stood by the

grave with the rest of them, and that Shakespeare's own pen

might still be lying in dust in the vaults of the old abbey.

There is something in the story very striking to the

imagination. One pictures to oneself the gathering of those

noble, dignified men of the Elizabethan age, whose thoughts

were at once so strong and so gentle, so fierce and so

tender, whose dress was so elaborate and stately. Perhaps in

years to come people may imagine to themselves the men who

stood only the other day round Robert Browning's grave, the

friends who loved him, the writers who have written their

last tribute to this great and generous poet. There are

still some eagle's quills among us; there are others of us

who have not eagles' quills to dedicate to his memory, only

nibs with which to pen a feeling, happily stronger and more

various than the words and scratches which try to speak of

it; a feeling common to all who knew him, and who loved the

man of rock and sunshine, and who were proud of his great

gift of spirit and of his noble human nature.

It often happens when a man dies in the fulness of years

that, as you look across his grave, you can almost see his

lifetime written in the faces gathered around it. There

stands his history. There are his companions, and his early

associates, and those who loved him, and those with whom his

later life was passed. You may hear the voices that have

greeted him, see the faces he last looked upon; you may even

go back and find some impression of early youth in the young

folks who recall a past generation to those who remember the

past. And how many phases of a long and varied life must

have been represented in the great procession which followed

Robert Browning to his honored grave! - passing along the

London streets and moving on through the gloomy fog;

assembling from many a distant place to show respect to one

Who never turned his back, but marched

breast forward;

Never

doubted clouds would break;

Never

dreamed, tho'right were worsted,

Wrong

would triumph;

Hold,

we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better,

Sleep

to wake.

FLORIN

WEBSITE

A WEBSITE

ON FLORENCE © JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE,

1997-2024: ACADEMIA

BESSARION

||

MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO

LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET

NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE

ALIGHIERI,

& GEOFFREY

CHAUCER

|| VICTORIAN:

WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S

'ENGLISH'

CEMETERY

|| ELIZABETH

BARRETT

BROWNING

|| WALTER

SAVAGE LANDOR

|| FRANCES

TROLLOPE

|| ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY

|| FLORENCE IN SEPIA

|| CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE

PROCEEDINGS

I, II, III,

IV,

V,

VI,

VII

, VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI'

|| EDITRICE

AUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA

WEBSITE

||

LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,

ENGLISH

|| VITA

New: Opere

Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence